calsfoundation@cals.org

Sebastian County Union War of 1914

The Sebastian County Union War of 1914 is one of the major instances of labor contention and violence in the state of Arkansas. Growing out of a mining operator’s attempt to save his badly run company by eliminating union labor, it resulted in murder, the destruction of property, and a lawsuit that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Sebastian County was one of the centers of the state’s coal-mining industry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, producing over 1.5 million tons of coal in 1913. Parallel to the strength of the industry was the strength of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), a union of which every miner in the state was a member. Resenting union power in the coalfields was Franklin Bache, who, with Heber Denman, operated coal-mining companies in a number of states, including large holdings in western Arkansas. Bache, then residing in Fort Smith (Sebastian County), was opposed to collective bargaining and tried, albeit unsuccessfully, in 1910 to open a mine in Sebastian County using only non-union labor; this mine was operated by a subsidiary company of Bache’s so as to give him cover for breaching the Joint Interstate Agreement of Operators and Miners, which had governed management-labor relations in the coal mines since 1903. In 1914, Bache tried again to eliminate union labor from a mine using a shell game maneuver by which one of his companies, Prairie Creek Coal Mining Company, leased its Mine No. 4 to another of his companies, Mammoth Vein Coal Mining Company, which had not operated before in Arkansas and was not a party to the 1903 agreement. Bache brought in armed guards and experienced strike breakers, including Roland Ford Barnes, and advertised the mine as strictly non-union.

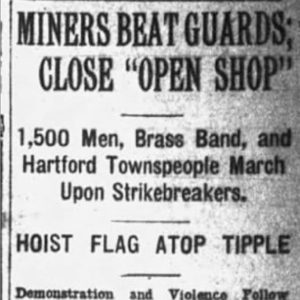

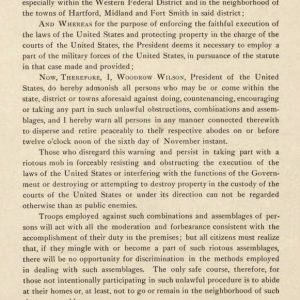

On the morning of April 6, 1914, more than 1,000 miners and their sympathizers gathered near Mine No. 4 to listen to speeches by Freda Hogan and others. The group then went to the mine to negotiate its closing, but the confrontation between the guards and the miners broke out into a fracas, in which the miners quickly overpowered their adversaries and proceeded inward. They shut down the mine’s boilers and drove off the non-union workers, thus resulting in the mine filling with water. The following day, Bache obtained a restraining order against union members. On April 20, UMW leader William McLaughlin led a strike on a nearby Coronado Coal Company mine, also owned by Bache. On May 9, Judge Frank A. Youmans of the United States District Court of the Western District of Arkansas issued a permanent injunction against the union, allowing Bache, in early June, to have U.S. district marshals located at the mine, though they remained only until July 15 and were given orders only to observe.

In the meantime, both Bache’s various mining companies in the area and union members were stockpiling weaponry. On July 13 and 16, the small mining camp of Frogtown, about a mile removed from Mine No. 4, came under fire from unidentified individuals. On July 17, approximately 200 union members and their sympathizers battled with company guards at the site of Mine No. 4, killing two Bache workers and nearly destroying the mine. Over the next few days, several other area mines were dynamited.

On July 25, all ten of the companies operated by Bache and Denman were placed in receivership, and Bache subsequently fired all but one employee of his various companies. Union leaders contended that the poor financial condition of Bache’s operations was the sole reason he had resorted to his attempt to eliminate union labor in his mines.

In September, Bache, through the Coronado Coal Company and his other holdings, brought suit against the United Mine Workers, local union members, and others who were alleged to have participated in the damage to the mines, arguing that the defendants had conspired to hamper interstate commerce. The trial did not begin until October 24, 1917, and less than a month later, the jury ruled for the plaintiffs, awarding the Bache companies $720,000 in compensation. The defendants appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which remanded it to a lower court, where it ended in a mistrial. Finally, on October 13, 1927, the case of Coronado Coal Company v. United Mine Workers of America was settled out of court, with the union paying only $27,500. However, by the time of the settlement, the legacy of a previous decade’s labor activism was all but forgotten, with most every mine in the state operating with non-union labor.

For additional information:

Alvarez, H. G. Fire in the Hole: The Story of Coal Mining in Sebastian County, Arkansas. Greenwood, AR: South Sebastian County Historical Society, 1983.

Sizer, Samuel A. “‘This is Union Man’s Country’: Sebastian County, 1914.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Winter 1968): 306–329.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Hogan, Dan

Hogan, Dan Coronado Coal Company Mine

Coronado Coal Company Mine  Sebastian County Union War Article

Sebastian County Union War Article  Woodrow Wilson Proclamation

Woodrow Wilson Proclamation

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.