calsfoundation@cals.org

Banking

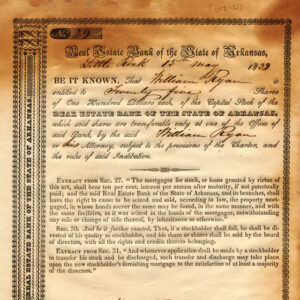

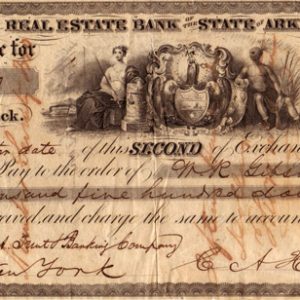

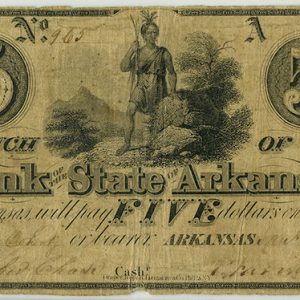

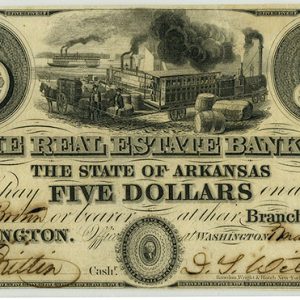

When Arkansas was admitted to statehood in June 1836, the first and second acts of the legislature that year authorized the chartering of two banks: the State Bank of Arkansas and the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas. Capital for the banks was obtained by substituting the credit of the state in the form of Arkansas bonds, to be sold presumably in the East or in the London market. Bond interest and principal were to be paid out of bank profits. The State Bank was government owned; shares of the Real Estate Bank were open to public subscription.

Both banks suspended the redemption of their bank notes (currency) in gold and silver coin in 1839 but continued to issue new currency to make additional loans. The notes declined in value, and prices rose appreciably. In the aftermath of the national Panic of 1837, loan defaults rose dramatically, and the two banks and their branches were closed between 1842 and 1844. The populace and the legislature became so disenchanted with banking that the Arkansas constitution was amended in 1846 to read: “No bank or banking institution shall be hereafter incorporated, or established in this State.” There were no incorporated banks in Arkansas until after the Civil War, though a few “private banks” (unincorporated banks) continued to function.

The constitution of 1868 established “free” incorporation laws but said little about banking. Another provision of the constitution specifically addresses “all corporations with banking and exchange privileges.” Several banks were incorporated under the authority of the new constitution.

Two Arkansas national banks were chartered in 1866 under the National Bank Act of 1864; one was voluntarily liquidated in 1870. An additional national bank was formed in 1872 and two more in 1882. Approximately twenty-three banks were operating as of 1882: four national banks and nineteen state and private banks. National banks were not authorized to establish branch offices; no branching restrictions were placed on state banks. The constitution of 1874 said little about banking but prohibited state-chartered banks from issuing their own currency. The latter reflected, in part, the increasing use of checking account banking and the availability of other forms of currency.

Arkansas incorporation statutes limited the liability of stockholders to the amount that they had paid for their stock. The requirements of incorporation were not onerous: $300 in capital and three stockholders. Many of the private banks incorporated under this law, primarily to obtain limited liability for their shareholders. With few restrictions on state banking, and virtually none on forming a bank, the new incorporation law led to the era of “wildcat” banking in Arkansas.

A group of prominent bankers formed the Arkansas Bankers Association in 1891. The following year, the association reported that there were eighty-three banks in the state, including ten national banks. The number of state banks increased to 118 in 1900, rose to 342 in 1904, then dropped precipitously to 272 the following year. State banks reached an all-time peak of 425 in 1914, the year the State Bank Department was formed, and declined to 404 in 1920. The number of national banks also increased during the period, rising from seven in 1900 to eighty-three in 1920.

The major topic of discussion at the annual convention of the Arkansas Bankers Association in 1904 and 1905 was a proposal to enact banking legislation and to establish a state agency to regulate state banks. The association formed a Banking Law Committee to address these issues. The committee recommended a bill that was agreed to by the convention. However, banking legislation was not forthcoming until Act 113 of 1913 became law. The major provisions of the act included creating the State Bank Department, appointing a bank commissioner to oversee the department, subjecting existing state banks to the regulations of the department, chartering state banks, enacting capital requirements and legal reserve requirements, increasing stockholders’ liability to double liability (repealed by a subsequent law), subjecting state banks to examinations and reports, and establishing legal lending limits. Finally, it appeared that state banks would be subject to meaningful regulation.

At least two African-American-owned banks were organized in Arkansas in the early 1900s. Jacob N. Donohoo established the Southwestern Investment, Trust and Banking Association in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1902. The following year, Mifflin W. Gibbs founded the Capital City Savings Bank in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Both banks failed in 1908 in the turbulence that followed the Panic of 1907.

The Federal Reserve System was created in 1913, after a long series of banking and financial panics from 1857 to 1907. The initial purposes of the new “central” bank included providing the nation with an elastic currency system, establishing a national system for the clearing and collection of checks, lending to commercial banks, and providing more effective supervision of commercial banks. The Federal Reserve’s powers have been vastly expanded over time to provide it with the means to promote a healthy financial system. However, as history shows, the Federal Reserve was unable to deal effectively with the economic and financial problems of the 1920s and 1930s.

Bank failures were not uncommon during the first two decades of the twentieth century, but new banks continued to be chartered at an alarming rate. Information about state banks is sparse and incomplete before the creation of the State Bank Department. However, from 1914 to 1920, eighty-three state banks were chartered, and thirty-one state banks suspended operation; the corresponding figures for national banks are thirty and four, respectively. Failures were due to turbulent economic conditions (six recessions during the period), state banks that could be organized with capital as low as $5,000, too many banks relative to population, most banks being too small to achieve economies of scale, and, in some cases, questionable management. But bank failures during the period almost seem benign compared with the 1920s and 1930s.

The 1920s began with a recession that lasted eighteen months. Three more recessions inflicted economic and social pain before the decade ended, including the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929. The economy was in recession some fifty months during the period. Arkansas and its banks were not immune to the turbulent economy.

Arkansas began the 1920s with 487 banks—404 state banks and eighty-three national banks. The decade ended with 420 banks—347 state banks and seventy-three national banks. The decline in number does not tell a complete story; some 109 banks suspended operations, and 127 new banks were chartered.

Like the 1920s, the decade of the 1930s began with the economy in recession, which lasted some forty-three months. Another recession began in May 1937 and ended thirteen months later. National unemployment rates were above twenty percent from 1932 to 1935, reaching a peak of some twenty-five percent in 1933, and unemployment remained above fifteen percent for the remainder of the decade. Unemployment rates did not drop from Depression levels until the economic impact of World War II was felt in 1941.

Arkansas began the decade of the 1930s with 420 banks and concluded it with 234. Some 288 banks suspended operations. Most of the suspensions occurred from 1930 to 1933, when 283 banks ceased operations, a few temporarily but most permanently. The most sensational failure occurred on November 15, 1930, when the American Exchange Trust Company of Little Rock failed to open its doors. The bank was the largest in the state and was part of the so-called A. B. Banks group of “chain” banks. The collapse of the American Exchange Trust Company led to the failure of some forty-five to fifty banks in the chain. Apparently, these banks failed because of their association with—and in the wake of—the collapse of the investment banking firm of Caldwell and Company of Nashville, Tennessee. The company controlled the largest chain of banks in the South. A. B. Banks subsequently was charged with, and successfully prosecuted for, accepting deposits in a bank he knew to be insolvent. He was sentenced to a year in prison, but he received a gubernatorial pardon.

The federal government responded to the banking debacle of the 1930s by enacting legislation to bring banks under greater scrutiny and regulation. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created in 1933 to insure bank deposits and to subject state-chartered banks to further government oversight.

The collapse of so many banks in Arkansas left a number of small communities without local bank services. New branching legislation was enacted in 1935, 1961, and 1973. The first two laws authorized limited service-branching (receiving deposits and cashing checks) but restricted branch location. The 1973 act authorized full-service branching. Branching was restricted to the city of the home office and to incorporated communities within the same county, provided that no other bank maintained its home office there.

Sweeping changes occurred in Arkansas’s banking structure during the last twenty years of the twentieth century. New branching legislation was enacted in 1989. The statute authorized countywide branching through December 31, 1993; contiguous county branching after December 31, 1993; and statewide branching beginning on January 1, 1999.

The Arkansas Bank Holding Company Act became law in 1983. A bank holding company is a company that owns or controls one or more banks. A holding company could provide banking services throughout the state by acquiring banks located in various communities and counties without violating the strictures of the branching law of 1973.

Federal law prevented holding companies from acquiring banks or bank holding companies located in another state unless that state had a specific law authorizing such transactions. In the 1980s, a number of states, including Arkansas, formed regional pacts and authorized holding companies to acquire other holding companies and banks located in member states. Thus, interstate banking via the holding company was introduced to the nation.

In 1994, Congress enacted legislation that overrode state law and allowed bank holding companies to acquire banks or bank holding companies located anywhere in the United States beginning in September 1995. Furthermore, a bank holding company was authorized to consolidate its affiliated banks into branches of one bank. Largely as a result, the number of banks in the nation dropped from 10,452 in 1994 to 7,085 in 2008. The corresponding figures for Arkansas are 257 and 143.

Reduction in the number of chartered banks is also caused by excess capacity in the industry, due largely to technology. Technology has reduced the need for “brick and mortar” branches, though branching networks continue to expand. Documents can be accessed from virtually any location via the Internet, and many banking transactions can be conducted through the use of automated teller machines (ATMs) and Internet banking.

For additional information:

Berry, Cody Lynn. “Early Arkansas Banking and Indian Removal, 1819–1860.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2016.

Fichtner, Charles C. “History of Banking in Arkansas.” In Arkansas and Its People—A History, 1541–1930, edited by David Y. Thomas. New York: American Historical Society, Inc., 1930.

McCracken, Lloyd, Jr. “The Early Banks of Craighead County, Arkansas 1878–1931, Part I.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 53 (January 2015): 3–15.

———. “The Early Banks of Craighead County, Arkansas, 1878–1931, Conclusion.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 53 (April 2015): 13–30.

Schweikart, Larry. Banking in the American South from the Age of Jackson to Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

———. “Banking in Antebellum Arkansas: New Evidence, New Interpretations.” Southern Studies 26 (1987): 188–201.

Worthen, W. B. Early Banking in Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing Co., 1906.

John A. Dominick

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Arkansas Loan and Thrift

Arkansas Loan and Thrift Bank OZK

Bank OZK Bowen, William Harvey

Bowen, William Harvey Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry First Security Bank

First Security Bank German National Bank

German National Bank Panic of 1893

Panic of 1893 Simmons First National Bank

Simmons First National Bank Stephens Inc.

Stephens Inc. Worthen, William Booker (W. B.)

Worthen, William Booker (W. B.) Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Stock Certificate  Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft  Arkansas State Bank Note, 1839

Arkansas State Bank Note, 1839  Bank of Centerton

Bank of Centerton  Bank of Prescott

Bank of Prescott  Booneville Bank

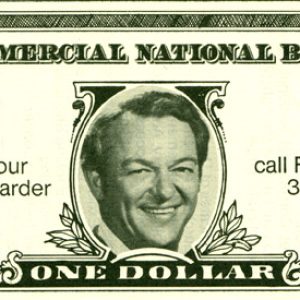

Booneville Bank  Commercial National Bank Flyer Featuring Frank White

Commercial National Bank Flyer Featuring Frank White  J. N. Donohoo

J. N. Donohoo  Farmers State Bank, Conway

Farmers State Bank, Conway  First National Bank

First National Bank  First State Bank

First State Bank  Melbourne Bank

Melbourne Bank  Real Estate Bank Note, 1840

Real Estate Bank Note, 1840  Security Bank

Security Bank  W. B. Worthen

W. B. Worthen  Worthen Building

Worthen Building

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.