calsfoundation@cals.org

Immigration

The peopling of Arkansas has taken place since prehistoric times, beginning with the migration of early Native Americans thousands of years ago. Europeans began to settle the area shortly after the arrival of the early explorers, such as Hernando de Soto, Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet, and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. Settlement took place largely as a result of gradual migrations into the state. Each new group helped define the cultural characteristics of Arkansas.

White Immigration, 1820 to 1880

Immigration into Arkansas between 1820 and 1880 was part of the general westward movement, a larger migratory process taking place in America. Some of the main reasons white people migrated to Arkansas were to seek adventure, to join family and friends already there, to obtain cheap and uncultivated land, and to improve their economic prospects.

Obtaining land was not difficult. The state and federal government offered public lands to settlers for as little as $1.25 per acre, and some programs even allowed them to pay for that land over a period of years. The Arkansas “Donation Law” of 1840 sweetened the prospects by offering tax-forfeited lands to those who would promise to pay taxes in the future. Beginning in 1850, the state offered swamp and overflow land to settlers for as little as fifty cents an acre, if the buyer agreed to build levees. By 1859, more than three million acres had been distributed under this program.

Settlers faced some problems, though, in their quest to move to Arkansas. Transportation was a significant problem. There were few roads, so the rivers and waterways were a primary means of travel during the early days. In time, roads were built, and after the Civil War, railroads began to traverse the state. But the lack of transportation infrastructure slowed migration.

The wide variety of soils and settings afforded newcomers choices. Most often, they moved to lands similar to those they left in the East. Single families or family groups from mountainous areas in Appalachia—most notably Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina—moved to the Ozark Mountains or Ouachita Mountains and developed small farms and livestock operations. Likewise, white people from the lowlands of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia moved to lowlands and river bottoms in Arkansas. Plantation owners moved to the Arkansas Delta and developed large acreages with significant slave labor.

Black Immigration of the Nineteenth Century

The black slave population was disproportionately distributed throughout the state, occurring predominately in the eastern and southeastern areas; by way of comparison, Benton County, in the northwestern corner of the state, had, by 1860, 384 slaves out of a total county population of 9,306, while Chicot County, in the southeastern corner, had 7,512 slaves out of a total county population of 9,234. This disproportionate settlement of slaves had enormous ramifications upon the development of politics and culture in Arkansas’s various regions that persisted beyond the Civil War—even to the present day. For one, the free, coerced labor slaves provided allowed many of their owners to accrue great wealth and thus shape the direction of state politics; therefore, government frequently implemented policies to cater to the slavocracy of the Arkansas Delta. This eventually included seceding from the Union, which the representatives of the second session of the Secession Convention approved specifically in order to protect the institution of slavery.

Briefly during Reconstruction, Arkansas actually attracted new waves of black immigration, being promoted somewhat in the black press as an actual land of opportunity. However, with the end of Reconstruction, whites reasserted a savage control upon the black populace, and those African Americans who resided here often sought to leave. Forms of labor were designed to keep African Americans in the Delta region; these included sharecropping and tenant farming, as well as peonage. The experience of African Americans in the Delta gives that region a far different character than the Ozarks and Ouachitas, and the genre of music known as the blues developed as an expression of that experience. Meanwhile, in the upland regions of the state, many communities began expelling their already meager populations of black residents, creating a wide swath of “sundown towns”—places where African Americans were prevented by locals from residing.

European Immigration

In the late nineteenth century, a new mechanism came into play: conscious immigration of people from other countries. One of the largest such immigrant groups was the Germans, several groups of whom migrated under the guidance of Catholic religious organizations such as St. Benedict’s Colony, which later became Subiaco Abbey, established in 1877 in Logan County. German-speaking immigrants, who had been recruited to help build the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, were the focus of settlement. In 1878, the first families arrived, and, by the end of that year, nearly 150 families had settled there.

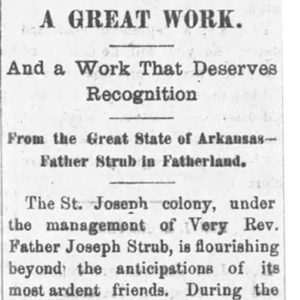

Subsequent groups of Catholic immigrants arrived in central Arkansas from Germany, Alsace-Lorraine, Switzerland, and Poland in the 1880s. They were recruited by a Catholic priest, in partnership with the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad. The railroad offered them inexpensive land in the Arkansas River Valley, as had been the case at Subiaco (Logan County). Fr. Joseph Stubbs, a Holy Ghost Father, recruited immigrants from regions of Europe where times were difficult and the practice of their religious faith was impaired by political action.

An early immigrant settlement was at Marche (Pulaski County), on the present-day western edge of North Little Rock (Pulaski County). There, Polish settlers established farms in the rich bottomlands of the Arkansas River. Approximately eighty-five families settled there. The mission of St. Joseph was established by German, Swiss, and French immigrants at Morrilton (Conway County), with an outlier at Conway (Faulkner County). Over time, the mission moved its headquarters to Conway. Immigrant settlements were subsequently established at Russellville (Pope County), Clarksville (Johnson County), Altus (Franklin County), Van Buren, and numerous smaller towns along the river and railroad.

Jewish immigrants to Arkansas, though always a tiny segment of the population, had a significant social and economic impact. Though present in the state as early as 1825, Jews immigrated in two significant waves. Prior to the Civil War, Jewish settlers trickled in from Germany and Central Europe to escape political unrest in their homelands. They formed small communities in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Batesville (Independence County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), and other cities. After the Civil War, these small communities grew as Jewish merchants with economic ties to Memphis, Tennessee; St. Louis, Missouri; Cincinnati, Ohio; and other larger cities moved to Arkansas seeking business opportunities.

A second wave of Jewish immigration began at the end of the nineteenth century, sparked by anti-Semitism and legal restrictions imposed upon Jews in Eastern Europe. A small number of Jews came to Arkansas from Poland and Latvia, drawn by family ties and economic opportunity.

Coal mining in western Arkansas drew a number of Eastern and Central European immigrants, who mined coal for decades in Coal Hill (Johnson County) and surrounding areas west of Clarksville. Fletcher Syglad of the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad recruited European workers for the mines. Slavic workers were brought in to break a strike leading to an incident known as the Jamestown War (also known as the Wheelbarrow Strike of 1915). Often, these immigrants did not bring their families, and they departed once they made some money to take home to Europe.

Another group of Central European immigrants settled in Prairie County between Hazen (Prairie County) and Stuttgart (Arkansas County) in 1894. The Slovak Colonization Society, organized by Peter V. Rovnianek and his associates, bought ten sections of land in Prairie County and moved an initial group of about fifty families to Arkansas by way of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Though they had worked as coal miners, like their fellow countrymen in the Coal Hill area of western Arkansas, these Slovak immigrants wanted to farm the fertile prairieland. They founded Slovaktown and later named it Slovak (Prairie County). In time, Bohemian and Russian immigrants settled the area, too, and the Russians built a Russian Orthodox church.

In 1890, Austin Corbin contracted with Prince Ruspoli, mayor of Rome to bring a group of Italian families to southeast Arkansas to grow and harvest cotton. They were brought in as part of a plan to replace African-American tenant farmers, who had migrated to northern cities to live and work. By 1897, nearly 1,000 Italian Catholics had migrated. However, many ended up leaving the area within five years, migrating to other areas of Arkansas, notably Pine Bluff, the Little Italy and New Dixie areas of Perry County, and Tontitown (Washington County) in northwest Arkansas.

Greeks were another small but influential group of European immigrants. Most settled in Little Rock, and later Greek immigrants relied on this early group for support. In the late 1920s, the Greek community in Little Rock numbered more than 200. By the 1940s, another thirty Greek families had moved to the Fort Smith area, where many were involved in the restaurant business supporting the military personnel stationed at what is now Fort Chaffee. There were also pockets of Greek immigrants in Pine Bluff and Hot Springs (Garland County).

Latino Immigration

In the first half of the twentieth century, Mexicans and other Latinos from central and South America began to immigrate to the state. During World War I and World War II, the federal government encouraged some Latinos to immigrate to relieve the labor shortages on local farms brought on by war. In the early 1950s, they worked mainly in agricultural roles, such as picking cotton. Frequently, immigration was temporary and workers would return to their permanent homes and families in Mexico, Central, and South America.

As the poultry industry developed in northwest and southeast Arkansas after World War II, especially after 1990, the immigration of these peoples accelerated. Commercial and residential construction also offered job opportunities. Early immigration was often in the form of individual workers, as in the coal-mining areas of the state. In time, families and extended families of Spanish-speaking peoples began to immigrate and settle permanently, mostly in the towns.

By 2009, northwest Arkansas was home to about half of the state’s Latinos. Churches experienced dramatic growth as they adapted to serving this burgeoning population. Over time, more Latinos began to move into better jobs, buy their own homes, and start their own businesses. Small stores and restaurants run by Latinos are commonly seen in northwest Arkansas and most of the rest of the state.

Involuntary Immigrants (Post-Slavery)

During the mid- to late twentieth century, several groups migrated to Arkansas involuntarily. Among these were Japanese Americans, Cubans, and Vietnamese.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The WRA was charged with moving more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry from California and other areas of the United States into relocation camps. Two of those camps, Rohwer and Jerome, were located in the Arkansas Delta counties of Desha, Chicot, and Drew near towns of the same names. These two Arkansas camps operated from 1942 to 1945 and housed nearly 16,000 Japanese American internees. Most of the internees left the state as soon as they were freed from imprisonment.

Another group of involuntary immigrants to Arkansas were refugees from Southeast Asia during 1975 and 1976. Fort Chaffee, located in the far western part of Arkansas near Fort Smith, was a logical site for housing large numbers of refugees. The site of an army training base during World War II, Fort Chaffee had many unused barracks available to refugees. During that period, Fort Chaffee hosted more than 50,000 refugees of the Vietnam War, gave them medical checkups, and helped them find new homes in the United States. Significant numbers of Vietnamese and Laotians eventually settled in Arkansas, as evidenced by the existence of various ethnic churches and temples. By 2009, there were Laotian Buddhist temples in Fort Smith and Springdale (Washington County) and Vietnamese Buddhist temples in Fort Smith and Bauxite (Saline County).

Cuban refugees comprise the final group of involuntary immigrants to Arkansas during the twentieth century. In April 1980, responding to local pressure, the Cuban government allowed American boats to come to the port of Mariel in Cuba to transport refugees to the United States. More than 125,000 refugees took advantage of the opportunity to leave Cuba. Initially, more than 19,000 Cuban refugees were relocated to Fort Chaffee. Many quickly found family and sponsors in other parts of the country and were quickly released, though some stayed for longer periods. In all, about 25,000 Cuban refugees spent time at Fort Chaffee by the time the last were released in early 1982. Almost no Cubans remained in Arkansas after their release. They preferred the more cordial social climates of New York and Florida.

Asian and Other Immigration

Shortly after the end of the Civil War, the Arkansas Valley Immigration Company was formed in order to bring Chinese immigrants to Arkansas in a scheme to replace black labor in the fields and thus counteract the growing power of black laborers. However, this plan never reached fruition, as many Chinese workers cut their contracts short; in addition, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented the further immigration of people from China. Those who stayed in Arkansas turned to running laundries and grocery stores, serving a largely African-American clientele.

Chinese Americans in Arkansas formed the Chinese Association of Arkansas during World War II in order to aid the American war effort. In addition, the group also promoted Chinese language programs and set up a language school in McGehee, though it operated but briefly. After the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Chinese citizens escaping from the communist takeover of the Chinese mainland were allowed to settle in the United States, and a number made their homes in the more urban areas of Arkansas. Today, Chinese Americans reside all across the state.

One of the better-documented immigrant groups are the Marshall Islanders of Springdale. Several news stories in print and in broadcast media featured this group between 2000 and 2010. The Marshallese began to migrate from their Pacific islands to Springdale in the late 1990s to escape high unemployment and lack of economic opportunity at home. Like Latinos, they moved to northwest Arkansas to work in the chicken plants and other factories. Springdale provided a lower cost of living and slower pace than many other areas of the U.S. By 2009, an estimated 6,000 Marshall Islanders lived and worked in Springdale.

Immigrants from India and from predominantly Muslim nations make up a fairly small percentage of the state’s population, but they are represented on the physical landscape through religious or cultural institutions built to serve these communities. Hindu immigrants from India began arriving in the state in the mid-1950s, and now Hindus operate the Vedanta Cultural Center in Little Rock as well as temples in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Bentonville (Benton County). In the 1980s, Arkansas State University (ASU) and the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) teamed with the government of Saudi Arabia to offer Saudi students customs official training. The Saudi government sponsored the construction of a mosque in Jonesboro for students, though now it serves a larger community. Other cities throughout Arkansas now feature Islamic centers.

Immigration and Retirement Communities

One development that has promoted immigration into the Ozark and Ouachita regions has been the creation of retirement communities. One of the first of these was Cherokee Village (Sharp County), which was originally designed as a summer resort but was transformed into a retirement community in the 1950s. Buyers largely from the North and the Midwest eagerly acquired lots in the new community, leading developer John A. Cooper to establish Bella Vista (Benton County) in 1965 and Hot Springs Village (Garland County) in 1970. Similar planned communities have included Horseshoe Bend (Izard County) and Fairfield Bay (Van Buren County). However, not all retirement-related immigration into the state’s uplands has been directed toward planned communities, for the city of Mountain Home (Baxter County) has been the beneficiary of a great deal of immigration, with its population growing from 2,105 in 1960 to 12,448 in 2010. As sociologist Gordon Morgan and others have noted, these immigrants are often attracted to the hill country due to the lack of racial diversity present there. In addition, because they have no children at home and often little investment in the communities in which they settle, they exert a conservative stance on issues of local government. For example, in 1973, residents of Baxter County voted down a proposed appropriation to develop a community college there; the result of this vote was largely attributed to the anti-tax bias of retirees, who could foresee no benefit to themselves through the development of a local college.

Conclusion

Throughout history, Arkansas has attracted some groups of immigrants due to the opportunities it seemed to offer them, even as other people were dissuaded from coming here by the state’s reputation in the wider world. Today, however, largely due to the mobility of the modern individual and family, people who hail from different states and countries may share the same community; even the once sparsely inhabited hill regions, as a consequence of advertising themselves to the world at large, are now populated with people from different backgrounds. Situated in the still otherwise non-diverse Ozark Mountains, the town of Bentonville (Benton County) has been transformed into a veritable international community, largely due to the influence of Walmart Inc., which is headquartered there. In addition, institutions such as colleges, universities, and hospitals attract people from across the country and across the world to settle in Arkansas. However, such immigration is not a new trend, for the state drew such people to it even from its earliest days.

For additional information:

Bearden, Russell E. “The False Rumor of Tuesday: Arkansas’s Internment of Japanese-Americans.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 1982) 327–339.

———. “Life Inside Arkansas’s Japanese American Relocation Centers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Summer 1989): 170–196.

Froelich, Jacqueline. “Islanders Moving to Arkansas.” National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=105731298 (accessed May 10, 2022).

Hronas, James and Helen. “A History of the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Community of Little Rock, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 39 (Fall 1991): 61–71.

LeMaster, Carolyn Gray. A Corner of the Tapestry: A History of the Jewish Experience in Arkansas, 1820s–1990s. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Rosen, Marjorie. Boom Town: How Wal-Mart Transformed an All-American Town into an International Community. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2009.

Schuette, Shirley Sticht. “Strangers to the Land: The German Presence in Nineteenth-Century Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2005.

Stewart-Abernathy, Leslie C. “Strangers in the Arkansas Uplands.” Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 46 (September 2012): 17–30.

Tsai, Shin-Shan Henry. “The Chinese in Arkansas.” Amerasia Journal 8 (Spring/Summer 1981): 1–18.

Walz, Robert B. “Migration into Arkansas, 1820 to 1880: Incentives and Means of Travel.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 17 (Winter 1958): 309–324.

George W. Balogh

Conway, Arkansas

Back-to-the-Land Movement

Back-to-the-Land Movement Hmong

Hmong Irish

Irish Harry Hronas

Harry Hronas  Iowa Immigrants

Iowa Immigrants  St. Joseph Colony Article

St. Joseph Colony Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.