calsfoundation@cals.org

Black Union Troops

aka: African American Union Troops

aka: United States Colored Troops

Many former African American slaves and freedmen from Arkansas answered President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to help put down the Confederate rebellion. Across the war-torn nation, 180,000 Black men responded. An estimated 40,000 lost their lives in the conflict. Lincoln later credited these “men of color” with helping turn the tide of the war, calling them “the sable arm.” The official records from the U.S. government credit 5,526 men of African descent as having served in the Union army from the state of Arkansas. Between 3,000 and 4,000 additional Black soldiers served in Arkansas during the war, including in artillery, cavalry, and infantry regiments. In addition, Black soldiers manned all of the batteries and fortifications at Helena (Phillips County) from 1864 until the end of the war in 1865.

Regiments of Black soldiers were organized in Arkansas during the American Civil War as fighting units of the U.S. Army. These regiments and others were all created on May 22, 1863, when the U.S. War Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops, most commonly known at the United States Colored Troops (USCT). All of the Black regiments were led by appointed white officers. On March 11, 1864, all USCT regiments were reassigned unit numbers, which historians differentiate with “old” and “new” classifications. For example, the Second Arkansas Colored Infantry became the Fifty-fourth U.S. Colored Volunteers. At first, Black soldiers were paid half of what white soldiers were paid. This was corrected in 1864, with some Black units receiving back pay for their services.

The Arkansas regiments included First Arkansas Battery–African Descent (Battery H, Second U.S. Colored Light Artillery), Eleventh U.S. Colored Infantry, First Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (Forty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry), Second Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (Fifty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry), Third Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry), Fourth Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry), Sixty-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry, Fifth Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (112th U.S. Colored Infantry), and Sixth Arkansas Infantry–African Descent (113th U.S. Colored Infantry). Battery E, Second U.S. Colored Light Artillery was recruited in Helena as the Third Louisiana Light Artillery (African Descent) and spent its entire term of service in Helena. Around 100 Black Arkansas men served in the U.S. Navy on the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

In addition, the Sixtieth U.S. Colored Infantry, raised in Iowa and Missouri, also served in Helena and elsewhere in Arkansas, the First U.S. Colored Cavalry took part in an 1863 skirmish in the state, the Third U.S. Colored Cavalry participated in an expedition to Arkansas, the Forty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry was stationed on the White River, the Fifty-first U.S. Colored Troops fought at Ross’ Landing, the Fifty-third U.S. Colored Infantry was stationed at St. Charles (Arkansas County), and detachments of the Sixty-third and Sixty-fourth Colored Infantry were detailed to Arkansas. The Fifth and Sixth U.S. Colored Cavalry and the Fourth U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery were stationed in Arkansas following the end of hostilities.

The First Arkansas Colored Infantry (Forty-sixth Colored Infantry) was assigned to the Department of the Gulf in June 1863. In addition to these regiments, other regiments of Black soldiers also participated in battles and skirmishes in Arkansas. The First Kansas Colored Infantry was one such regiment. It was made up of ex-slaves from Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri. Black troops fought for the Union despite the Confederate Congress passing on May 1, 1863, a proclamation to the effect that any captured Black soldier fighting for the Union would be executed. Arkansas’s Black regiments were garrisoned at Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Helena, Little Rock (Pulaski County), DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) from late 1863 to the end of the war in 1865.

The First Arkansas Colored Regiment had its own marching song. Penned by Captain Lindley Miller of the First Arkansas, the song was sung to the tune of “John Brown’s Body” and was published in 1864. The opening stanza expressed the pride the soldiers felt in their work:

Oh, we’re the bully soldiers of the “First of Arkansas,”

We are fighting for the Union, we are fighting for the law,

We can hit a Rebel further than a white man ever saw,

As we go marching on.

Time and time again, the Black soldiers proved their prowess and courage in battle. A writer for an abolitionist newspaper in Leavenworth, Kansas, remarked upon the courage of Black troops at the Skirmish of Island Mound in Missouri on October 29, 1862, between Union and Confederate forces. “It is useless to talk any more of negro courage,” he wrote. “The men fight like tigers, each and every one of them, and the main difficulty was to hold them well in hand.” (This battle was the first in which organized Black troops fought, occurring before Black regiments were officially approved by the federal government.) Major General James Blunt wrote after the Battle of Honey Springs in Indian Territory, in which the First Kansas Colored participated, “I never saw such fighting as was done by the Negro regiment….The question that negroes will fight is settled; besides they make better soldiers in every respect than any troops I have ever had under my command.”Writing after the battle of the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry on April 30, 1864, division commander Brigadier General Frederick Salomon said the Black troops under his command fought with conspicuous gallantry.

At the Engagement at Poison Spring, fought on April 18, 1864, the Black soldiers of the First Kansas suffered heavy casualties—117 died and sixty-five were wounded. The death toll was aggravated by the fact that Confederate soldiers executed the captured and wounded men left on the field. These atrocities were witnessed firsthand by the regiment’s white commander, Colonel James M. Williams. It also gave rise to the battle cry among his troops to “Remember Poison Spring!”

After the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry, fought just a few days later on April 30, 1864, an officer of the Second Kansas Colored explained, “It was a question…whether the blacks would fight.” But the Black soldiers’ prowess in battle convinced not only the Confederates they would be a worthy enemy, but it also convinced many of the white soldiers who were fighting alongside them. Even the German-American soldiers of the Twenty-seventh Wisconsin, who harbored contempt for all Blacks in general, agreed the Black troops had done well at Jenkins’ Ferry. There were reports of Black soldiers committing war atrocities, too, cutting the throats of the Confederate wounded left on the battlefield at Jenkins’ Ferry. Many Black soldiers had witnessed firsthand the brutal treatment given wounded African Americans and their officers by the Confederates, and they knew they would be given no quarter.

In total, Black troops fought in twenty-eight battles and skirmishes in Arkansas during the war. According to the Official Army Register of the Volunteer Force of the United States Army, 1861-1865, these battles included:

| Date | Battles | Troop | AKA |

| July 4, 1863 | Helena | Second Arkansas Colored Infantry | Fifty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry |

| February 14, 1864 | Ross’ Landing | Fifty-first U.S. Colored Infantry | First Mississippi Infantry (African Descent) |

| February 17, 1864 | Horse-Head Creek | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| March 20, 1864 | Roseville Creek | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| April 13, 1864 | Indian Bay | Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry | Third Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

| April 13, 1864 | Prairie D’Ane | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| April 13, 1864 | Prairie D’Ane | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| April 18, 1864 | Poison Spring | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| April 24, 1864 | Camden | Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry | Fourth Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

| April 26, 1864 | Little Rock | Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry | Fourth Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

| April 30, 1864 | Jenkins’ Ferry | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| April 30, 1864 | Jenkins’ Ferry | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| May 4, 1864 | Jenkins’ Ferry | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| May 28, 1864 | Little Rock | Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry | Fourth Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

| July 2, 1864 | Pine Bluff | Sixty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry | Seventh Louisiana Infantry (African Descent) |

| July 26, 1864 | Wallace’s Ferry | Battery E, Second U.S. Colored Light Artillery | Third Louisiana Light Artillery (African Descent) |

| July 26, 1864 | Wallace’s Ferry | Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry | Third Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

| July 26, 1864 | Wallace’s Ferry | Sixtieth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Regiment Iowa African Infantry |

| August 2, 1864 | Helena | Sixty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry | Seventh Louisiana Infantry (African Descent) |

| August 24, 1864 | Fort Smith | Eleventh U.S. Colored Infantry | |

| October 22, 1864 | White River | Fifty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Third Mississippi Infantry (African Descent) |

| December 18, 1864 | Arkansas River | Fifty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Arkansas Colored Infantry |

| December 19, 1864 | Rector’s Farm | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| December 24, 1864 | Fort Smith | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| January 8, 1865 | Joy’s Ford | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| January 17, 1865 | Chippewa Steamer | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| January 17, 1865 | Lotus Steamer | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| January 18, 1865 | Clarksville | Seventy-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry | First Kansas Colored Infantry |

| January 24, 1865 | Bogg’s Mill | Eleventh U.S. Colored Infantry | |

| May 4, 1865 | Saline River | Eighty-third U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Kansas Colored Infantry |

| May 4, 1865 | Saline River | Fifty-fourth U.S. Colored Infantry | Second Arkansas Colored Infantry |

| June 29, 1865 | Meffleton Lodge | Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry | Third Arkansas Infantry (African Descent) |

In 2013, the first state monument honoring Black Union troops was erected in Freedom Park in Helena-West Helena. Ten years later, the Central Arkansas Library System announced that it was seeking to create a memorial statue for Black Union troops at Library Square in downtown Little Rock.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin Cole. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission, 1967.

Burkhart, George S. Confederate Rage, Yankee Wrath: No Quarter in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

Christ, Mark K. “‘Forfeit… two months pay and be restored to duty’: Some Court Records of the Fifty-Seventh USCT.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Winter 2021): 124–125.

———. “‘If we could get with the Yankees, then we’d be free’: The Fifty-Seventh U.S. Colored Troops.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Winter 2021): 116–123.

———. “The 112th and 113th Regiments USCT.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Winter 2021): 126–127.

———. “‘They Will Be Armed’: Lorenzo Thomas Recruits Black Troops in Helena, April 6, 1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Winter 2013): 366–383.

———. “‘To let you know that I am alive’: Civil War Letters of Capt. John R. Graton, First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Spring 2019): 57–80.

Christ, Mark K., ed. “All Cut to Pieces and Gone to Hell”: The Civil War, Race Relations, and the Battle of Poison Spring. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

———. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: Free Press, 1990.

Hargrove, Hondon B. Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003.

Lause, Mark A. Race and Radicalism in the Union Army. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Nichols, Ronnie A. “Emancipation of Black Union Soldiers in Little Rock, 1863–1865.” Pulaski County Historical Review 61 (Fall 2013): 76–85.

O’Neal, Rachel. “CALS to Memorialize the State’s Black Union Troops.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 2, 2023, pp. 1D, 5D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/apr/02/cals-to-memorialize-the-states-black-union-troops/ (accessed May 16, 2023).

Ringquist, John Paul. “Color No Longer a Sign of Bondage: Race, Identity and the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment (1862–1865).” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2011. Online at https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/8372 (accessed May 16, 2023).

Robertson, Brian K. “‘Will They Fight? Ask the Enemy’: United States Colored Troops at Big Creek, Arkansas, July 26, 1864.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Autumn 2007): 320–332.

Trudeau, Noah Andre. Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War 1862–1865. Boston: Back Bay Books, 1999.

Urwin, Gregory J. W. Black Flag over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Walls, David. “Marching Song of the First Arkansas Colored Regiment: A Contested Attribution.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Winter 2007): 401–421.

Steven L. Warren

Overland Park, Kansas

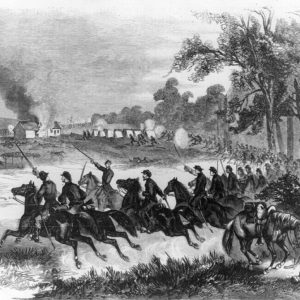

Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Hickory Station, Skirmish at

Hickory Station, Skirmish at Union Occupation of Arkansas

Union Occupation of Arkansas Battle of Honey Springs

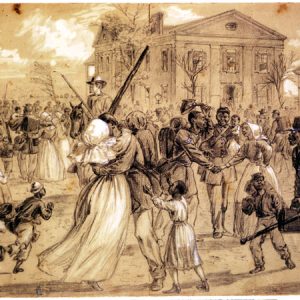

Battle of Honey Springs  Celebrating African American Soldiers

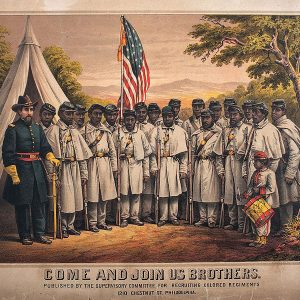

Celebrating African American Soldiers  Colored Regiments Recruitment Poster

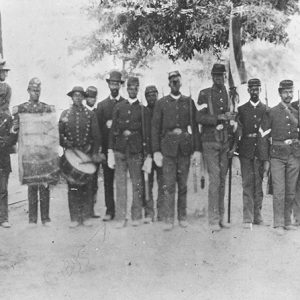

Colored Regiments Recruitment Poster  Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry

Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry  James M. Williams

James M. Williams

Outstanding information. I am writing about a “colored” soldier and his family during the Civil War who served in Helena in the 56th. I am delighted to find events corroborated in your historical encyclopedia.