calsfoundation@cals.org

Black Hawk War of 1872

The Black Hawk War was a Reconstruction-era political and racial conflict in Mississippi County that occurred in 1872—not to be confused with two earlier incidents both called the Black Hawk War, which were clashes between Native Americans and white settlers in other states. Little is known about the event, including the origins of its name.

During Reconstruction, the radical wing of the Republican Party controlled most elected offices. Many judges, prosecutors, and registrars were intensely disliked by local residents, who had little say in their own affairs and who resented the granting of civil rights to African Americans, of which Mississippi County had a sizeable population. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was very active in the area, resulting in Mississippi County being put under martial law after the 1868 general election.

Prior to the November 1872 election, Republican “carpetbagger” Charles B. Fitzpatrick was appointed Mississippi County registrar. The Arkansas Gazette, which was consistently opposed to the Republican political agenda, described Fitzpatrick as “a born bandit” who arrived in Arkansas in 1869 and began a career as a “striker” at the state legislature—that is, one who would introduce a bill or measure in the legislature with the idea of being bought off. He was soon appointed circuit judge of the Fourth Circuit overseeing Madison, Boone, Marion, Van Buren, and Newton counties. According to the Gazette, Fitzpatrick, accompanied by an armed guard of African Americans, rode through his circuit imposing taxes on the local population, giving inflammatory speeches, conspiring to kill opponents, and committing offenses such as leaving Jasper (Newton County) without paying his bills. When he arrived in Mississippi County, Fitzpatrick’s presence aggravated an already highly charged atmosphere.

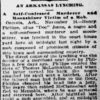

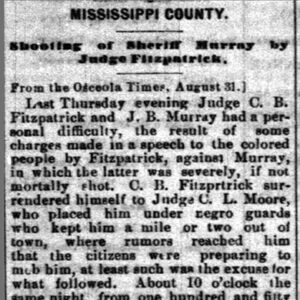

Late in August 1872, Fitzpatrick made a speech alleging that Sheriff J. B. Murray, as a tax collector, had embezzled school taxes. On August 29, the two met on the porch of the post office in Osceola (Mississippi County). Fitzpatrick offered to shake hands with Murray, but Murray struck at Fitzpatrick with his fists. (One account says Murray was wearing brass knuckles.) Fitzpatrick shot Murray in the abdomen, mortally wounding him.

Fitzpatrick later surrendered himself to Judge C. L. Moore. The judge was ill and told Fitzpatrick to surrender to a justice of the peace. Fitzpatrick reportedly declined to do so and demanded that he be provided with a guard of African Americans until the judge was well enough to proceed with the trial. He gathered a group of seventy-five to 100 guards and was admitted to bail of $3,000. He stayed in the vicinity and continued his duties as registrar. The Circuit Court convened in early October to try Fitzpatrick for Murray’s murder.

During the afternoon session of the court, twenty armed white men paraded through Osceola. Judge Palmer, a special judge of the court who presided because the regular judge was away on another assignment feared trouble and adjourned court. The next day, he arrived to find neither witnesses nor jurors, so he again adjourned. Judge Palmer reprimanded Fitzpatrick and his reported 200 men. Fitzpatrick reluctantly agreed to disperse his men. Palmer then went to the other side of town and did likewise to another group of men gathered with Captain Charles Bowen, a former Confederate captain and local KKK leader. Fitzpatrick instead took his forces to the southern edge of town. Bowen moved south toward Fitzpatrick’s position. Shots were exchanged, and one African-American man of Fitzpatrick’s party was killed. The next morning, Bowen’s group went south to confront Fitzpatrick’s group and found that the Fitzpatrick forces had gone into adjacent Crittenden County seeking reinforcements.

Fitzpatrick reportedly went to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he hoped to drum up support for martial law and the militia for Mississippi County. After visiting Osceola and interviewing residents there, U.S. Senator Stephen Dorsey and Asa Hodges, recently defeated for the U.S. House seat from the district that included Mississippi County, decided that martial law and the presence of the militia were not warranted.

The New York World of October 24, 1872, referred to the incidents, in terms of the classic racist and partisan rhetoric of the times, as “a foray of infuriated blacks armed to the teeth, and led on by a scoundrel carpet-bagger upon a town, with avowed intent to slay the men and violate the women thereof.”

Mississippi County was a hotbed of violent, racist activity at the time, and many African Americans likely felt that they needed to take action to protect their newfound freedoms. Fitzpatrick’s flight and the unwillingness of the state government to intervene in local affairs seem to have left local African-American citizens open to reprisals. In November of 1872, the Memphis Avalanche reported, “On Wednesday last the dead bodies of two more negroes were found afloat in the river near Somers. …This makes, altogether, seven dead men that have been found mysteriously slain since the late riotous proceedings commenced.”

Fitzpatrick escaped prosecution, though how is not clear. He was removed as Mississippi County registrar but was the Republican nominee for the state legislature, despite not being a county resident. He was defeated by Hiram M. McVeigh, who had helped lead local citizens in the skirmishes that preceded Fitzpatrick’s departure. During the 1873 session of the state legislature, there was an attempt to pardon Fitzpatrick for Murray’s murder even though he had never been tried for or convicted of the crime. Fitzpatrick was reported to have left the state late in 1873; one source claims that he headed for Mexico, while another holds that he went to Texas and was killed shortly thereafter, though an anonymous author in the Arkansas Gazette wrote that he returned to Kentucky and served as a Commonwealth attorney.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

Bowen, Charles. “The Autobiography of Captain Charles Bowen, Osceola Pioneer.” Osceola Times. December 25, 1975, 1–3.

“Captain Bowen Tells of Early Days in Mississippi County.” Delta Historical Review, Fall 1996, 4–13.

Edrington, Mabel F. History of Mississippi County Arkansas. Ocala, FL: Ocala Star Banner, 1962.

Smith, John I. Forward from Rebellion: Reconstruction and Revolution in Arkansas, 1868–1874. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1983.

Ruth C. Hale

Burdette, Arkansas

Chicot County Race War of 1871

Chicot County Race War of 1871 Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Phillips, Henry (Lynching of)

Phillips, Henry (Lynching of) Black Hawk War Article

Black Hawk War Article  Stephen Dorsey

Stephen Dorsey  Asa Hodges

Asa Hodges

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.