calsfoundation@cals.org

Malaria Control Projects in Southeast Arkansas

Two malaria control demonstration projects in southeast Arkansas during the Progressive Era showed not only that the disease could be controlled, but also that control was economically feasible. The project in Crossett (Ashley County) targeted mosquito breeding sites, while the one in the Lake Village (Chicot County) area studied protection by mechanical means. Both were noteworthy successes, though local governments often failed to follow up on those successes.

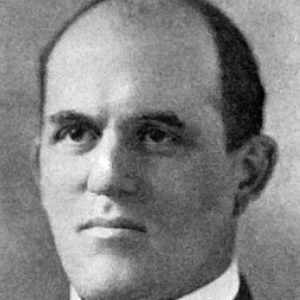

Malaria control was a logical extension of hookworm eradication projects sponsored by the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease. In 1915, Dr. Wickliffe Rose, who headed the commission, said that “malaria was responsible for more sickness and death than all other diseases combined.” The disease sapped the vitality of individuals, and the economic cost due to illness was “incalculable,” Dr. William H. Deaderick, author of a medical textbook on the endemic diseases of the South, concluded in 1911. “The most prevalent and devastating disease in the South is malaria,” Charles Willis Garrison, the Arkansas State Health Officer, wrote in 1930. U.S. Public Health Service surgeon Dr. Rudolph H. von Ezdorf, in a study of the economic impact of malaria on sawmills and cotton plantations, found that the average worker lost two weeks of work due to malaria, and because of decreased efficiency, employers had to hire twenty-five to fifty percent more workers during the summer malaria season.

Given the social and economic costs of malaria, the Arkansas State Board of Health in 1913 required physicians to notify the board of all cases. In his presidential address to the Arkansas Medical Society in 1914, Dr. Frank B. Young noted that malaria remained widespread and was “economically the most harmful” disease in the state at the time. Young said that physicians must not only treat individuals, but also destroy the breeding habitat of the mosquito. His address set forth the guidelines implemented in the malaria control projects at Crossett and at research sites near Lake Village. Young advocated draining or oiling breeding sites such as ditches and stagnant ponds, but he added that more was needed, telling his fellow physicians that the eradication of malaria “can only be accomplished by a persistent educational campaign in which every doctor should be the leader in his home community.”

The physicians in Arkansas provided an internal impetus for control efforts, and the external forces of the United States Public Health Service and the International Health Commission, successor to the hookworm commission, set the stage for demonstration projects. On September 25, 1913, Deaderick proposed to John D. Rockefeller a plan “relative to a campaign for the eradication of malarial fevers in the South.”

Dr. Rudolph H. von Ezdorf continued preliminary survey work in Arkansas in 1915, deciding that the malaria projects should proceed along two lines. The focus of studies in Mississippi was to control malaria by treating the carriers. The second line of study was to set up demonstration projects in Arkansas; two demonstration sites were selected, a rural unit in Chicot County and an urban unit in the company town of Crossett.

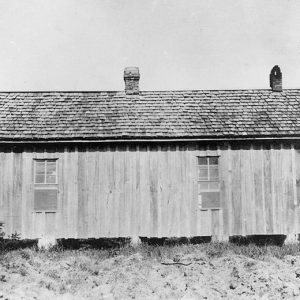

Drs. Robert C. Derivaux and H. A. Taylor, successor to von Ezdorf, headed the project in Crossett, and on April 10, 1916, the demonstration began with the creation of a map showing all potential mosquito breeding sites. During the summer, workers cleaned 9,244 linear yards of old ditches, installed 3,177 yards of new ditches, and cleaned 4,844 yards of street ditches. The workers also applied oil or larvacide to borrow pits, streams, and ditches as well as four ponds and 311 water barrels kept in the sawmill and along the railroad lines.

The results were remarkable. In 1915, the year before the demonstration project, local physicians had an estimated 2,500 calls to treat malaria. With the control project in 1916, that number dropped to 741. The per capita cost was $1.24, well below the $2 cost of a visit to a physician. There were other benefits. In July 1916, Dr. Garrison noted that Crossett was “virtually free of mosquitos,” where “they were almost intolerable” a year before. The Crossett Lumber Company commended the project for “practically eliminating malaria” and “greatly improving the sanitary and general health conditions of the town.”

In Chicot County, the demonstration project centered on the 4,000-acre Red Leaf Plantation and nine other plantations. Rather than mosquito control, the project emphasized educational efforts and mechanical protection, including installing galvanized screens on homes, treating human carriers using quinine, and using a combination of screening and treatment.

The results in Chicot County were also impressive. While the prevalence of malaria remained at about the same level as in prior years in the other parts of county, in the demonstration area, “malaria and other illness, with attendant economic loss, have been markedly less.” At the end of the demonstration project in December 1916, twenty of 104 people in the control group tested positive for malaria, while only twenty-two of 394 in the demonstration area tested positive. A total of 142 people had both the preliminary and post-demonstration tests, and the number with positive results reported dropped from seventeen to five. The researchers found those in the demonstration area averaged only six cents per person in economic losses due to malaria. That, combined with a per capita cost of $1.76 for the screening and other items, came to a total cost of $1.82, well below the average economic loss of $2.52 for those not in the demonstration area. Those who received only quinine and did not have their homes screened had average costs of fifty-seven cents per capita, significantly less than the $2.52 loss figure.

The International Health Board, the new name for the International Health Commission, concluded that the initial projects “demonstrate the practicability of anti-mosquito measures as a means of controlling malaria…from the standpoint both of expense and the degree of control attained.” With the success of the projects in Crossett and Lake Village, the International Health Board expanded projects to other towns in Arkansas and other states in the South.

In January 1919, Wickliffe Rose of the International Health Board noted that the demonstrations had been a success and suggested that the State Board of Health take over further control efforts. Arkansas and other states, however, proved reluctant to provide funds for the expansion of control projects. In addition, the cities and towns failed to continue the work. Lunford Dickson Fricks, the surgeon in charge of the Public Health Service’s Office of Malarial Investigations, noted that there was “considerable difficulty in getting these old cities to maintain the work even after it has proven successful.” Garrison believed that the local health units were not organized enough to take advantage of cooperative programs.

In spite of the failures of local governments to continue malaria projects, as late as 1973, an Arkansas State Department of Health official cited the Crossett project as one of “the earliest attempts to combat vectors and vector-borne diseases.” Projects such as the one at Lake Village and a later one at Dermott (Chicot County), according to Dr. P. W. Covington, a field director for the International Health Board, had “attracted national attention and the pioneer work done in this state has been used as a model for malaria control campaigns.”

For additional information:

Fosdick, Raymond D. The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1952.

Malaria Control: A Report of Demonstration Studies Conducted at Urban and Rural Areas. Public Health Bulletin No. 88. Washington DC: Government Printing office, 1917.

Robinette, Robert L. “Vector Control in Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society 70 (July 1973): 87–88.

Von Ezdorf, R. H. “Malarial Fevers—Prevalence and Distribution in Arkansas.” Public Health Reports 29 (January 1914): 1–13.

Williams, Greer. The Plague Killers. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1969.

David Moyers

Ashley County Ledger

Health and Medicine

Health and Medicine Public Health

Public Health Smallpox

Smallpox Automatic Oil Drip

Automatic Oil Drip  Crossett Street Drain

Crossett Street Drain  Charles Willis Garrison

Charles Willis Garrison  Malaria Control in Hamburg

Malaria Control in Hamburg  Malaria Control in Hamburg

Malaria Control in Hamburg  Malaria Protection

Malaria Protection

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.