calsfoundation@cals.org

Plum Bayou Culture

Plum Bayou culture was a people who built religious centers with a formal arrangement of earthen platforms or mounds that bordered a rectangular open area used for religious and social activities. The misnamed Toltec Mounds site in central Arkansas (preserved by the Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park) was the primary center. Plum Bayou culture, dating about AD 650 to 1050, was one of the first cultures to have such centers in Arkansas. Most of the Plum Bayou people lived in small villages and hunted, fished, gathered wild plant foods, and farmed. Villages were present primarily on the floodplains of the Arkansas and White rivers, but they were also in the adjacent uplands.

Plum Bayou developed out of the earlier (300 BC to AD 650) Baytown culture, in which people lived in small, scattered communities and depended primarily on hunting and fishing with little farming. Plum Bayou preceded Mississippian culture (circa AD 900 to 1600), in which people lived in large permanent villages, depended on farming, and built mounds. Plum Bayou culture had contacts with early Caddoan culture in the Red River and Ouachita River valleys and upstream along the Arkansas River Valley into Oklahoma, with early Mississippian culture up the White River and Black River and in the St. Francis River area of northeastern Arkansas, and with Coles Creek culture in the lower Mississippi River Valley.

Village and Mound Sites

Most of the people lived in small villages with multiple households or in single-household farmsteads on high ground adjacent to streams, lakes, and abandoned river channels. Rivers such as the Arkansas and Mississippi that drain nearly level floodplains changed their courses, creating new channels and abandoning old ones. The land adjacent to new channels was flooded frequently, while the land near abandoned channels was more protected. The Native Americans built their villages near the abandoned channels. Sites are size-ranked into four groups: single household, multiple household, multiple household with mound, and multiple mound sites. Site size was related to the activities taking place and by the social status of the people associated with them. Small sites were occupied by a single family who farmed, hunted, and collected wild foods within a few miles of their home. Temporary activities such as hunting or collecting nuts also result in small sites. Larger multiple household villages were occupied for several years, and people farmed the land around the village and hunted and collected wild food from the surrounding area. Some of the larger villages had mounds built up of earth to make a raised place where religious ceremonies were conducted. The leaders lived in these larger communities. In the Arkansas River floodplain, the Toltec Mounds (Lonoke County), Coy (Lonoke County), and Hayes (Arkansas County) sites were multiple-mound sites. In the floodplain drained by the White and Cache rivers, sites with mounds include Baytown (Monroe County), Roland (Arkansas County), Chandler (Prairie County), Dogtown, and Maberry (Woodruff County). Some sites had single mounds, but most of these have been destroyed by modern farming, and without excavated samples of artifacts, the culture and time period are difficult to identify. Toltec Mounds near the Arkansas River and Baytown near the White River were the largest sites.

Only the Toltec Mounds Site has had major excavations (1977 to 1990). It had eighteen mounds (identified by letters) arranged around two open areas or plazas. Mounds A and B were forty-nine and thirty-eight feet tall, respectively, while Mound C was about twelve feet tall. The other mounds were less than five feet tall. Only Mound C is known to have been a burial mound. The low mounds were built as flat-topped platforms that were used in rituals and ceremonies or had houses of religious leaders on them. Thick deposits of animal bone and tools used in butchering and cooking indicate that these deposits were the remains of community feasts. The Toltec Mounds Site is distinctive in that it has a ditch and earthen embankment over a mile long around three sides; the fourth side is on a lake. The ditch and earthen embankment was a kind of construction that was present at important religious centers in the Mississippi Valley over a period of several hundred years earlier than at Toltec. Its continued use is evidence for continuity and continuing development and change in the cultures of eastern Arkansas and adjacent Mississippi Valley.

The Baytown Site, with nine mounds, is a smaller version of the Toltec Mounds Site, without the ditch and embankment. It has mounds arranged around an open plaza, and the two tallest mounds were twenty and ten feet tall, with others five feet tall or less. Based on initial research in the 1940s, the Baytown Site was considered to be the major site of the Baytown culture (AD 300 to 650). Distinctive styles of flat-based pottery jars, hemispherical bowls, and stone points used on darts were associated with Baytown culture. Baytown culture was recognized over a large portion of the lower Mississippi River Valley. Plum Bayou culture developed out of Baytown culture; there was not a sharp divide between the two. The two cultures overlap in time, and pottery decorative designs of Plum Bayou culture were present at the Baytown Site, indicating that use of that site continued after AD 650.

Food and Housing

Plum Bayou people grew domesticated plants native to eastern North America, such as maygrass, little barley, amaranth, and chenopodium, with lesser amounts of sunflower, sumpweed, knotweed, squash, and bottle gourd. Corn, or maize, was a minor plant that was present in late Plum Bayou sites. Acorns and hickory nuts were important in the diet. Wild fruits such as persimmons, plums, cherries, and various berries and grapes were also eaten. People hunted white-tailed deer, squirrels, raccoons, turkeys, passenger pigeons, and migratory wildfowl using bows and arrows. They caught various species of fish depending on what lived in the nearby bodies of water. Aquatic turtles were also caught for food. People were dependent on all of these resources, although the importance of one or another varied seasonally.

Little archaeological evidence for Plum Bayou culture houses has been excavated, but remains of houses at a few small excavated sites indicated that they were apparently made of a pole framework with cane mats for walls and grass thatch for the roof. The support posts of a pole framework survive as dark round stains of soil in the ground, and burned and charred cane mats and thatch are evidence of construction materials.

Containers and Tools

Various containers and tools were made of wood, cane, bark, and vines. Pottery containers were made of clay and fired to make them durable. The paste of the pottery was tempered with grog consisting of crushed fragments of broken pottery and burned clay. Vessel shapes included conical jars used in cooking and storage—which had flat bottoms, constricted necks, and flaring rims—and deep, hemispherical bowls and shallow bowls. Most of the pottery was not decorated, but some bowls had fine clay and red pigment applied to the surfaces. Other bowls had various designs incised or punched into the upper rim of the vessel. Decorative motifs and styles were often distinctive for a culture; however, when the decoration shows similarities with neighboring cultures, it indicates communication and contact between cultures. Plum Bayou motifs show a strong connection with contemporary styles present in the lower Mississippi Valley and along the Gulf Coast.

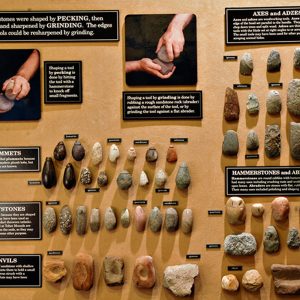

Stone tools were made of both fine-grained materials—such as chert, novaculite, and quartz crystal—that contained silica and could be chipped into shape and of dense materials that were ground into shape. These materials are generally not available on the floodplains of the Arkansas and White rivers, which are composed primarily of fine sands, silts, and clays deposited by floodwaters. Rivers draining mountainous areas carry rocks down to the floodplain, and rivers have gravel bars composed of pebbles and cobbles. The kinds of stone present on an archaeological site indicate how far the people went to obtain needed materials. Cobbles of chert (a dense material variously colored by impurities) were collected from the nearby river and from the Ozarks, especially in the area of the White and Black rivers. Novaculite, quartz crystal, sandstone, quartzite, shale, siltstone, syenite, and lamprophyre were obtained from the Ouachita Mountains. Common stone tools included arrow points, knives, and scrapers used to kill and butcher animals and to make tools and artifacts of wood, cane, and bone. Axes and adzes were used for woodworking, and sandstone tools were used to grind seeds and crack nuts.

Ornamental and Religious Items

Not all of the items or objects excavated from Plum Bayou sites were common or utilitarian. Some objects were made of raw materials that came from considerable distances. Beads were made of gastropod (snail) shells and of conch shells from the Gulf Coast. Fragments of copper from the Great Lakes area were made into beads and ornamental items. These materials or the finished items were obtained by trade with the neighboring groups of people rather than Plum Bayou people traveling great distances to obtain the materials.

Other nonutilitarian items were made of materials that could be obtained within Plum Bayou territory or nearby. They were rare, and most of these have been excavated from the larger sites rather than from farmsteads and small villages. Some of these items were included in graves, but they were also present in other deposits on the mounds. Archaeologists theorize that the use of these items was restricted to the leaders or to special activities. Ornaments included hairpins and small perforated disks (perhaps clothing ornaments) made of deer bone. Thin rectangular stone bars with two perforations may have been worn on the chest as ornaments. Red, white, and yellow paints were made from hematite, limonite, and galena. Religious items include effigy figurines of birds made of clay and stone. Birds such as the woodpecker, barred owl, hawk, eagle, and pelican were likely caught for the feathers or to make fans of the whole wings rather than for food. Modified platform pipes were made of a dull pink siltstone and of clay. Elaborately decorated pottery vessels were used in religious ceremonies rather than as everyday food bowls.

Community

Most of the people lived in the small farmsteads and villages located near land good for farming. Daily activities were devoted to obtaining food and making the items they needed to live comfortably, such as clothing, tools, containers, and houses. Activities varied seasonally—planting crops in the spring, tending them in the summer, fishing in the summer, hunting deer and collecting hickory nuts and acorns in the fall. They probably traveled to the religious centers throughout the year for ceremonies.

Social and religious leaders lived at the larger mound centers and planned and directed the construction of the mounds. They conducted religious ceremonies and organized people to provide for feasts and distributed the food to those in need. Raw materials for nonutilitarian items discussed above were brought into these centers and used by the leaders and their families. The leaders may have held formal, inherited offices that were passed down through certain family lines. Both the Toltec Mounds and Baytown sites were important religious centers where people came for ceremonies. Archaeologists do not have enough information to say just how powerful the Plum Bayou leaders may have been.

The End of Plum Bayou Culture

Between AD 900 and 1000, other cultures in neighboring regions became powerful. This included the people around the Spiro Site in the Arkansas River Valley to the west (near present-day Fort Smith in Sebastian County); people in the Red River valley of southwestern Arkansas and adjacent Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas; people living near the Tensas River, Yazoo River, and mouth of the Red River in Louisiana and Mississippi; and the Mississippian culture people in northeastern Arkansas and adjacent Tennessee, Missouri, Kentucky, and Illinois. They had more complex social organization and leadership with a greater accumulation and display of wealth than the Plum Bayou. They shifted to a greater dependence on maize agriculture and built sturdy houses in large villages. They changed the technology for making pottery vessels and produced elaborate vessel shapes with complex designs.

For some as yet unknown reason, the people of Plum Bayou culture did not participate in these changes, and the religious centers were abandoned. Some people continued to live in the Plum Bayou region, but they no longer used the Toltec Mounds and Baytown sites as religious centers, and they did not build new centers or villages with mounds. Archaeological information on these changes and the people after Plum Bayou that lived in the region is still to be developed.

For additional information:

Nassaney, Michael J. “The Contributions of the Plum Bayou Survey Project, 1988–1994, to the Native Settlement History of Central Arkansas.” The Arkansas Archeologist 35 (1996): 1–50.

———. “The Historical and Archaeological Context of Plum Bayou Culture in Central Arkansas.” Southeastern Archaeology 13 (1994): 36–54.

Rolingson, Martha Ann. “Plum Bayou Culture of the Arkansas–White River Basin.” In The Woodland Southeast, edited by David G. Anderson and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

———. Toltec Mounds: Archeology of the Mound-and-Plaza Complex. Research Series No. 65. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2012.

———. Toltec Mounds and Plum Bayou Culture: Mound D Excavation. Research Series No. 54. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1998.

Martha Ann Rolingson

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park

Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park  Plum Bayou Artifacts

Plum Bayou Artifacts

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.