calsfoundation@cals.org

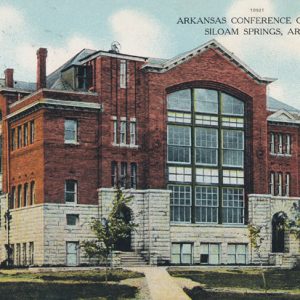

Arkansas Conference College (ACC)

Arkansas Conference College (ACC) was founded in Siloam Springs (Benton County) in 1899. Though short-lived, ACC provided an academically rigorous education, primarily for the benefit of Arkansans. As a school that emphasized classical studies along with practical skills (such as typing), ACC challenges stereotypes about early twentieth-century rural Arkansas.

ACC was established by the Methodist Episcopal Church of Arkansas. Its founding president, Dr. Thomas Mason, had helped to found Philander Smith College (PSC) in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the late 1870s. Like Fisk University in Tennessee, where Mason’s wife had taught, PSC was started in the post–Civil War era to help freed slaves and their children become part of mainstream society. By contrast, in some of ACC’s early promotional literature the school appealed to prevailing sentiment and advertised itself as being in the peaceful city of Siloam Springs, where there were many churches and “no negroes.” At the same time, Mason’s previous work with colleges for black students caused him no discernible personal problems in Siloam Springs.

ACC’s primary purpose was to train students for business, ministry, teaching, and “service” in Arkansas. The large majority of its students were Arkansans, and most were women. Though ACC was associated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, it was broadly Protestant. By the standards of its day, ACC seems to have been liberal. The school’s statement on the study of biology is vague but points to an acceptance of theistic evolution. The school’s annual bulletins also suggest that ACC’s professors approached the Bible primarily as a moral and philosophical text.

In addition to providing post–high school instruction, ACC hosted an academy, as did Siloam College, which succeeded ACC, though it survived just one year. These short-lived academies were among several founded in Siloam Springs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two others being Congregational Academy and Welty Academy.

ACC held its first classes in September 1899; it had four professors and about thirty-three students in the college and academy. The number of students waxed and waned over the years, though enrollment never approached the 200 students ACC’s facilities could accommodate. In 1914, there were twenty-eight students in the college and thirty-seven in the academy. Many of the school’s alumni went on to become teachers in Arkansas’s public schools. By 1914, five of these alumni were school principals.

Like many small colleges, ACC was never secure; it never attracted the sustained favor of wealthy benefactors. Between 1899 and 1915, ACC was not able to offer its teachers a set salary; instead, tuition fees were divided among them. This spurred high faculty turnover, and few professors remained at ACC longer than two years. An institutional memoir locally published for the school’s tenth anniversary acknowledged that the “history of the college from the beginning is a story of defeat and disaster followed by success and triumph.” The successes were primarily personal.

Despite its difficulties, ACC maintained high standards. The school’s bulletin from 1905 states that only young people with high ideals and ambition were welcome there. Freshmen were expected to have gained a command of Latin before beginning their college studies, and every student at ACC was required to study advanced Latin. By 1915, the college also included departments of expression (i.e., rhetoric and debate), music, commerce, English, history, modern languages (German and French), philosophy, and Greek. Students who came to ACC without the knowledge of Greek grammar were allowed to study in the academy, though for college credit.

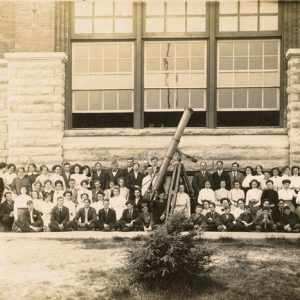

The college’s academic bulletins were serious, but the school sometimes marketed itself using the kind of inflated language that was common at the time. ACC boasted of having the largest telescope in Arkansas, and the school sponsored a photograph of its community with the telescope placed center stage. At another time, ACC trumpeted the exploits of nine-year-old Margeurite Simpson, “the youngest practical stenographer the world has ever known.” Simpson had learned her skill in ACC’s department of commerce.

Information about what caused ACC to fold is lacking, though its low number of students, along with its regular appeals for financial help, suggest persistent fiscal difficulty. Too, the relative remoteness of Siloam Springs likely played a role. ACC closed in 1917 and was succeeded by Siloam College, which closed the following year. In September 1919, classes began at Southwestern Collegiate Institute, forerunner to John Brown University (JBU), west of downtown Siloam Springs. The only clear link between ACC and JBU is the work of Isaac Loder Lowe, a vice president at ACC who later taught at the much more conservative and evangelical new college.

For additional information:

Siloam Springs Museum. Siloam Springs, Arkansas.

Preston Jones

John Brown University

Bartell, Fred Wallace

Bartell, Fred Wallace Mountain Mission Schools

Mountain Mission Schools Arkansas Conference College

Arkansas Conference College  Arkansas Conference College Baseball Team

Arkansas Conference College Baseball Team  Arkansas Conference College

Arkansas Conference College  Arkansas Conference College Women's Basketball Team

Arkansas Conference College Women's Basketball Team

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.