calsfoundation@cals.org

Irish

Irish migration to Arkansas took place throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in three distinct settlements. Over the years, Irish residents of Arkansas have made their mark on the state, exemplified in organizations such as the Irish Cultural Society of Arkansas. About fifteen percent of Arkansans claim Irish or Scotch-Irish ancestry.

The first wave of Irish immigration concerned the Scotch-Irish (sometimes called Scots-Irish), who were descendants of eighteenth-century Ulster Protestant immigrants. The term Scotch-Irish acknowledges the seventeenth-century mass Scottish migration to Ireland’s northernmost province, Ulster—a migration that left indelible marks on the culture, including stark differences in religion and nationalistic attitudes that distinguished the Protestant, pro-British “Scotch-Irish” from their Catholic, Gaelic, and generally anti-British neighbors. Scotch-Irish immigrants to the United States had settled the mountainous backwoods of Appalachian Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia, as well as the Piedmont region of the Carolinas. With the explosion of the cotton economy in 1818, droves of white families from the eastern United States—including many descendants of the original Ulster Protestant migrants—scrambled to claim lands in the Southwest in the hopes of attaining fortune that “King Cotton” promised, while other families looked to those territories for any kind of economic opportunity. Thousands of settlers of Irish heritage migrated to the Arkansas territory; often seeking out land similar to their places of habitation back east, they gravitated predominantly toward the Ozark Mountains in the northwestern section of the territory, though some families built communities in the southern Ouachita Mountains.

Author Russel L. Gerlach differentiated class groups among the Ulster Protestants, as well as Irish Protestants from the island’s southern provinces. He noted that the most sophisticated and affluent Protestant immigrants tended to be overrepresented among the planter classes found in the eastern Arkansas Delta, while “low-end Scotch-Irish” generally included semiliterate or illiterate “nomadic hunter and farmer types from various mountains.” The Ulster Protestants included several Christian denominations that are commonplace in present-day Arkansas, including Church of Christ, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist. This initial wave of Irish immigrants to Arkansas and their descendents maintained Ulster traditions in the mountain regions of the state, such as practicing stringently individualistic Protestantism, hunting, playing fiddle music, performing “buck” or rhythmic step dancing, and making whiskey.

Certain colloquialisms that are associated with working-class southern culture are rooted in the native language characteristics used by Ulster Protestants and those they invented upon arrival in the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains. Expressions such as “hillbilly” and “howdy” are derived from slang fostered in Ulster and transplanted into Arkansas. These cultural expressions have been caricatured and exaggerated as “redneck,” “white trash,” or “cracker” customs in popular culture. However, Arkansans of Ulster Irish heritage proudly celebrate that inheritance today through festivals such as the annual Ozark Mountain Music Festival and the Arkansas Folk Festival.

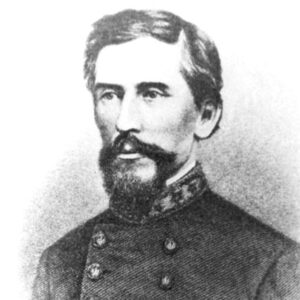

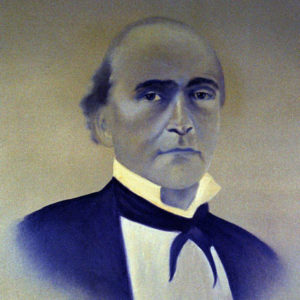

Arkansas’s second migration of Irish and Irish-descended settlers arrived after the territory became a state. A son of immigrants, New Jersey–born Quaker Harris Flanagin settled in Arkansas in 1839 and was elected as the state’s Confederate governor in 1862 before the fall of Little Rock (Pulaski County) the next year. Some Irish immigrants also made their way to Arkansas during the mid-century potato blight known as the Great Famine. This calamity affected the fortunes of every class in Ireland and caused the diaspora of more than one million immigrants. Among these was a Protestant pharmacist, Patrick Cleburne of County Cork. Cleburne settled in Helena (Phillips County) in 1850 and served the Confederacy as the commander of the First Arkansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War, earning distinction as the only Irish immigrant to achieve the rank of brigadier general. Irish-American Unionist Isaac Murphy succeeded Harris Flanagin as the first Reconstruction governor of the state.

However, the largest migrations of Irish men and women occurred under the direction of the Roman Catholic Church. Father Thomas Hore of County Wexford led an expedition of approximately 300 Gaelic Irish, Catholic emigrants to the United States in 1850. His goal was to supplement the small number of Irish Catholics in Little Rock with scores of new immigrants to create a thriving Irish Catholic colony in the central part of the state. Historians debate whether the priest was attempting to evacuate refugees of the Great Famine, or if the party represented members of the farming communities in Counties Wicklow and Wexford who were less devastated by the agricultural disaster but nevertheless believed that post-Famine Ireland offered few opportunities. Three shiploads of Irish migrants entered the United States through the Port of New Orleans, Louisiana, and made their way to Little Rock along the Mississippi River and Arkansas River. Upon arrival in the capital city, however, Hore determined that he was unhappy with the location. From that point, the emigrant party split into six companies that settled in Texas, Missouri, Iowa, and Louisiana, while a third of the group stayed in Arkansas to join the Irish Catholics of Little Rock and establish an enclave in the west at Fort Smith (Sebastian County).

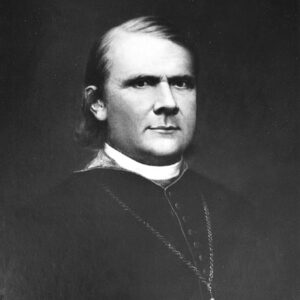

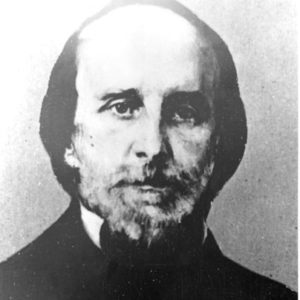

The Irish Catholics who stayed in the capital joined the sparse community established by the state’s first Catholic bishop, Irish native Father Andrew Byrne, who had dedicated St. Andrew’s Cathedral in 1846. In addition to St. Andrew’s, Byrne enlisted twelve members of the Irish Sisters of Mercy (four sisters and eight others who had not taken their final vows) to come to the fledgling Diocese of Little Rock in the 1850 to promote Catholic education. With their leadership, St. Mary’s Academy (now Mount St. Mary Academy) was established in 1851. The prominence of the school ensured that non-Catholic families began enrolling their daughters in a process that further centered Catholicism, and Irish culture, as cornerstones of the state capital. Central Arkansas’s Irish connection was bolstered after the end of the Civil War and following the death of Byrne. A Famine refugee, Father Edward Mary Fitzgerald, originally of County Limerick, Ireland, was consecrated as the state’s second Catholic prelate in 1867 and arrived in Little Rock on St. Patrick’s Day of that year. Like his predecessors, Fitzgerald attempted to grow the state’s Irish Catholic population, but emigration from Ireland to the United States, particularly the South, slowed dramatically in the post-Famine years. Nevertheless, under Fitzgerald’s four decades of leadership, Arkansas Catholicism expanded to include fifty-one parishes and four orders of nuns who ministered across the state.

“Irishness” was not limited to religion or its institutions; nineteenth-century travelers throughout the South and in Arkansas commented on the prevalence of Irish immigrants and customs, sometimes unfavorably. One visitor to the state remarked that state legislators who spent more than a quarter of a year in the capital were forced to endure “Irish hole[s], dignified with the appellation of hotel.” Despite religious and ethnic differences between the Ulster Protestants and the Gaelic Irish Catholics who immigrated to Arkansas, the two groups shared cultural appreciations—such as music, hunting, and dancing—that non-Irish settlers and travelers to the state observed, including the gambling and excessive drinking regularly attributed to Gaelic Irish-Americans.

Nevertheless, the small but culturally influential wave of Gaelic Irish Catholic migration to Arkansas in the 1850s and 1860s was, in certain ways, bolstered by the third Irish emigration to the state. In the 1980s, the United States suffered a dearth of nursing professionals that prompted communities to campaign to attract foreign medical professionals into the country. This crisis particularly affected rural states where potential healthcare workers had left to find opportunities in metropolitan areas. The shortage of nursing and medical professionals in Little Rock propelled the capital city’s hospitals to recruit new staff from Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. The success of the city’s campaign resulted in central Arkansas welcoming an influx of Irish workers who added or reinvigorated ethnic customs that had become part of the state’s heritage in the mid-nineteenth century.

Considering the national nursing shortage only temporary, most of the respondents intended to work in the United States for only a few years. However, as the new immigrants married and began rearing families, many determined to stay. To ensure that they preserved their Irish heritage, these families formed the Irish Cultural Society of Arkansas (ICSA) in 1996. This association offers itself to Arkansas community service projects, including educational and food sustainability efforts. Moreover, part of the mission of the ICSA serves to instruct Arkansans in Irish history and Irish contributions to the United States. Since the organization’s founding, this third wave of immigrants has made annual festivals, including a St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Little Rock, a cornerstone of Arkansas’s Irish community. Music and traditional dancing, as well as folk art and storytelling, help the ICSA showcase traditions and customs that first became part of the state’s heritage in the early nineteenth century.

Since their arrival in the 1980s, founding members of the ICSA and their supporters have revitalized a legacy of Irishness in the state that continues to be a source of pride to Arkansans. In 2010, the federal census revealed that approximately thirteen percent of Arkansans claim Irish heritage, while nearly two percent claim Scotch-Irish ancestry.

For additional information:

Bragg, Don C. “The Langtrees of Little Rock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 66 (Summer 2018): 42–76.

Byrne, James P., Philip Coleman, and Jason F. King. Ireland and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History, Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2008.

DeArmond, Fred. “Scotch-Irish Heritage.” White River Valley Historical Quarterly 4, no. 4 (Summer 1971). Online at http://thelibrary.org/lochist/periodicals/wrv/v4/n4/s71i.htm (accessed September 16, 2021).

Gerlach, Russel L. Immigrants in the Ozarks: A Study in Ethnic Geography. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1976.

Hayes, Jan. History of Mount St. Mary’s Academy, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1851–1987. St. Louis, MO: Sisters of Mercy, 1987.

Irish Cultural Society of Arkansas. http://www.irisharkansas.org/about-us (accessed September 16, 2021).

Joslyn, Mauriel P., ed. A Meteor Shining Brightly: Essays on Maj. Gen. Patrick R. Cleburne. Milledgeville, GA: Terrell House Publishing, 1998.

Martin, Amelia. “Migration—Ireland, Fort Smith and Points West.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 2 (September 1978): 43.

McGowan, Mrs. John. “The First Irish Families of Cotton Plant (Richmond).” Rivers and Roads and Points in Between 2 (Summer 1974): 26–30.

McWhiney, Grady. Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989.

Motherwell, David. “Scots-Irish Immigration to the Ozarks.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly 65 (Summer 2020): 58–64.

Stratton, Terry D., et al. “Recruitment Barriers in Rural Community Hospitals: A Comparison of Nursing and Nonnursing Factors.” Applied Nursing Research 11, no. 4 (1998): 183–189.

Weaver, Jack W. “From Scotland to Arkansas: Migration and Settlement Patterns of the Scotch-Irish.” American Speech 74, no. 3 (1999): 328–332.

Woods, James M. Mission and Memory: A History of the Catholic Church in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1993.

Misti Nicole Harper

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Byrd, Henry

Byrd, Henry Kennedy, John

Kennedy, John World's Shortest St. Patrick's Day Parade

World's Shortest St. Patrick's Day Parade Andrew Byrne

Andrew Byrne  Patrick Cleburne

Patrick Cleburne  Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald  Harris Flanagin

Harris Flanagin  Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy  World's Shortest St. Patrick's Day Parade

World's Shortest St. Patrick's Day Parade

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.