calsfoundation@cals.org

Heckaton (?–1842)

Heckaton was the hereditary chief of the Quapaw during their long and painful removal from their homelands in Arkansas during the 1830s.

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, fewer than 600 Quapaw remained of the thousands who had lived in the region in the late seventeenth century. Most of these lived in three traditional villages near Arkansas Post (Arkansas County). Each village had its own leader, and one leader was overall tribal chief by family inheritance. A few Quapaw lived in homesteads along the Arkansas River as far north as the site of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

For a decade, there were no official relations between the Quapaw and the American government. After the War of 1812, however, the number of settlers in pre-territorial Arkansas increased, and the desire to remove Indians from the East into present-day Arkansas and Missouri dominated policy decisions in Washington. These two trends were at odds with each other, but both led to Quapaw removal.

Heckaton became primary chief some time after the Louisiana Purchase. By 1816, there were pressures to extinguish Quapaw land claims. Heckaton led a delegation of Quapaw leaders to St. Louis to meet with the territorial governor William Clark. Land cession was the ulterior motive for American officials’ calling this first official meeting with the Quapaw. At this meeting, the Quapaw signed an agreement which called for them to relinquish claims to some lands in exchange for an annuity and other economic considerations.

But this agreement was not acceptable in Washington DC. In 1818, Heckaton and a delegation were back in St. Louis for another conference. This time, the secretary of war intended to acquire Quapaw land for the relocation of Indians then living east of the Louisiana Territory. The Treaty of 1818 required the Quapaw to relinquish claims to a vast tract extending from the Mississippi River west to the edge of the plains and situated between the Arkansas and Red rivers. They retained a small wedge-shaped parcel extending from the south bank of the Arkansas River, beginning at Little Rock and extending downstream, to the Ouachita and Saline rivers in south Arkansas.

Although Heckaton and other tribal leaders thought that the Quapaw were now secure, territorial residents wanted to end all Quapaw land rights and evict the tribe. By 1825, despite Heckaton’s public pleas to remain, the Quapaw were forced to cede all remaining lands and move to the Red River in Louisiana to consolidate with the Caddo.

The Red River sojourn was disastrous. The Caddo did not want the Quapaw to join them. The Red River flooded Quapaw cornfields repeatedly, and people starved. A group under the leadership of an American-appointed chief, Saracen, returned to the Arkansas River, where their plight finally attracted food aid and other support from Governor George Izard and a variety of sympathetic Arkansas citizens. The remainder stayed under Heckaton’s leadership in Louisiana until, a few at a time, most of them, including Heckaton, had drifted back to Arkansas by late 1830. The split between followers of Saracen and those of Heckaton continued to affect tribal affairs for decades.

In Arkansas, the Quapaw were now landless and separated from the annuities that would only be disbursed in Louisiana. Heckaton traveled to Washington in late 1830 to negotiate for assigned lands in Arkansas and continued payments. He illustrated Quapaw openness to Western culture by enrolling four boys in the Choctaw Academy in Kentucky and asked for funds to support them. The tuition money was subsequently subtracted from the tribal annuity.

The Quapaw remained in limbo for nearly three years until May 1833, when Heckaton again presented the tribe’s desire to remain in Arkansas to the Stokes Commission, a government-authorized panel empowered to resolve all Indian problems west of the Mississippi River. At a meeting held in New Gascony, south of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Heckaton once again argued for the Quapaw to remain in Arkansas, offering that they would retreat to swampy areas in order to allow white settlers access to good farmland. Unmoved, Commissioner J. F. Schermerhorn declared that the Quapaw had to leave Arkansas, and the meeting concluded with Heckaton reluctantly accepting a draft treaty assigning the Quapaw to a tract of land west of Missouri in far southeast Kansas.

The treaty was not implemented until 1834. As the departure date approached, many Quapaw decided instead to return to Red River in Louisiana or to join other Indians in east Texas. Heckaton led the remainder west. Roll records indicate 176 Quapaw began this journey and that 161 were still in the party at the end. The non-arrivals may have died, returned to southeast Arkansas, or embarked for friends and relatives among the Texas Cherokee.

Bureaucratic mismanagement uprooted the removal group once more before they settled on their legally assigned tract in northeast Oklahoma in 1839. The Kansas location was contested. A tract in northeast Oklahoma was substituted, but the Quapaw began building homes and sowing fields before the tract was surveyed; when the survey was finished, some Quapaw found themselves on the wrong plot of land once again. Heckaton died in northeast Oklahoma in 1842.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1804. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Baird, W. David. The Quapaw Indians: A History of the Downstream People. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Ann M. Early

Arkansas Archeological Survey

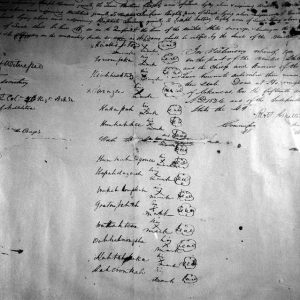

Quapaw Treaty of 1824

Quapaw Treaty of 1824

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.