calsfoundation@cals.org

Tyronza (Poinsett County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º29’24″N 090º21’31″W |

| Elevation: | 210 feet |

| Area: | 1.56 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 716 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 17, 1926 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

573 |

639 |

656 |

601 |

510 |

777 |

858 |

918 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

762 |

716 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tyronza is located on U.S. Highway 63, midway between Jonesboro (Craighead County) and Memphis, Tennessee, in southeastern Poinsett County. It is best known as the birthplace of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU).

Pre-European Exploration through European Exploration and Settlement

The town site was home to an earlier community existing at least as far back as AD 1300–1400. An 1884 archaeological survey conducted by the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology reported that as many as forty-nine Native American mounds had existed in the immediate vicinity. At that time, only seventeen remained; most of the others were destroyed either by early settlers preparing the land for farming or by the crews who constructed the railroad bed in the early 1880s. The 1884 excavations revealed the mounds to be primarily dwelling sites. Today, there are visible remnants of only three mounds left within the town. Due to the town site’s location near the Tyronza River and the existence of the mound community, it is possible that the Hernando de Soto expedition passed through the area.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In 1883, the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Gulf Railway constructed a raised bed for the tracks, as well as a small wooden depot known as Tyronza Station, named for the nearby Tyronza River. The depot was adjacent to a general store and post office called Perkins, which had been established earlier that year to provide for the needs of the crews building the railroad. In 1888, the post office was changed to Tyronza to match the name of the depot.

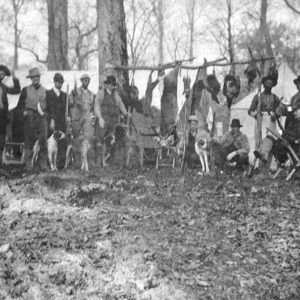

By 1889, Tyronza had grown to include two general stores and a stave factory. Tyronza was primarily a lumber town. The land was heavily forested, the market for timber was strong, and the railroad opened up the market for the lumber as well as for the cotton that was soon to replace it as the region’s main cash crop.

Early Twentieth Century

By 1920, Tyronza was a commercial center for the cotton economy. Local merchants eagerly extended credit to small farmers utilizing the crop lien, which allowed the farmer and his family to buy needed items and pay for them in the fall when the cotton was harvested. The 1920s were a time of growth for the area because of its dependence on human labor instead of mechanization. In 1926, an enthusiastic group of business and professional men in the community petitioned the county court to incorporate, and on May 17 of that year, the city of Tyronza officially came into existence.

Almost immediately, economic conditions began to change in the region. The Flood of 1927 caused a great deal of damage in eastern Poinsett County. The flood was followed by the stock market crash in 1929, and a severe drought lasting two years began in 1930. In 1930, the Bank of Tyronza failed, and small farmers lost their land either to merchants foreclosing on crop liens or to the county for back taxes. The majority of the land ended up in the hands of a small number of men who utilized sharecroppers and tenant farmers to work it.

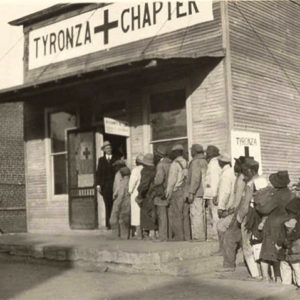

By 1934, living conditions for tenant families were critical. With the assistance of two local businessmen, eighteen local tenant farmers met in a rundown schoolhouse just west of Tyronza and formed the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU). The STFU offices were housed in downtown Tyronza in the back of a dry-cleaning establishment until escalating violence forced them to move the offices to Memphis.

While Tyronza is predominantly white as of 2008, that was definitely not the case in years past. During the period from 1920 to 1940, African Americans constituted an estimated fifty percent of the population of the area. Most of the black population moved on with the decline in sharecropping. Tyronza had a separate school for the black children until 1968, located at the same place as the first STFU meeting in 1934. The site of that historic meeting was burned down shortly thereafter to prevent further union activity, and a school and church were built there a short time later. Originally called Cherubim Church, the name was later somehow converted into Cherry Beam; the church is still active and has a large cemetery.

World War II through the Modern Era

During World War II, people flooded out of the Delta by the thousands, bound for military service or work in the defense industry in the cities. The shortage of labor—although relieved somewhat by utilizing German prisoners of war from the prison camp at nearby Marked Tree (Poinsett County)—forced the local planters to mechanize. Without the sharecropper and tenant farmer families to sustain the economy, Tyronza began to fail. In the 1950s, Tyronza General Supply, the last of the commissary type stores, closed.

In the 1970s, Tyronza experienced a population surge as a more affluent population began looking for a home out of the city. Fully one half of the homes in the town were built during this time period. Present-day Tyronza exists primarily as a rural suburb, with the majority of the residents driving to work in nearby Memphis or Jonesboro.

In 2003, the city gave the Mitchell-East Building, the original offices of the STFU, to Arkansas State University to restore and convert into the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum, which opened its doors in October 2006.

In 2007, the Tyronza Water Tower was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

For additional information:

Grisham, Cindy. “When Hope Grows Weary: An Arkansas Delta Town in Place and Space.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2012.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Poinsett County, Arkansas: History and Families. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 1998.

Thomas, Cyrus. Report on the Mounds Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

Cindy Grisham

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Flood Victims

Flood Victims  Joe Hong Grocery

Joe Hong Grocery  Poinsett County Map

Poinsett County Map  Southern Tenant Farmers Museum

Southern Tenant Farmers Museum  Southern Tenant Farmers Museum

Southern Tenant Farmers Museum  Tyronza Church

Tyronza Church  Tyronza Flood Refugees

Tyronza Flood Refugees  Tyronza Hunters

Tyronza Hunters  Tyronza Street Scene

Tyronza Street Scene  Tyronza Street Scene

Tyronza Street Scene  Tyronza Water Tower

Tyronza Water Tower

There is a huge time gap here in the history of Tyronza, 1970-2003. There’s so much more to the history of this town including Gibbs Grocery. How Mr. Gibbs got rockabilly artist Eddie Bond to come play music. Mr. Gibbs is a huge part of Tyronza’s history! He didn’t play that fiddle very well, but he sure could strum “The Wabash Cannonball” on his banjo. He’d sit in front of his store and moan the blues on his guitar. He had many stories to tell and many told of him. And what about the arson of his property? Mr. Gibbs nearly burned alive in this arson, but just in time he was saved by a couple of heroes whose names I have forgotten. And he died a year after the arson. There is no mention of how Mr. Gibbs brought music to the town in order to bring revenue to his grocery store and the other businesses. No mention of the Country Music Hall where hundreds of bands played. Tyronza is a city of musical heritage as well as the Native Americans, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, and all the resources it possesses. The arson left the city a ghost town.