calsfoundation@cals.org

Redeemers (Post-Reconstruction)

The term “redeemers” was self-applied by those who succeeded in returning the Democratic Party to prominence at the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas, generally dated to 1874. The Republican Party came to power in the state in 1868 with the passage of the Congressional Reconstruction Acts. Arkansas’s second Republican governor, Elisha Baxter, elected in 1872, worked to curry favor with conservative Democrats by appointing many to office in an effort to build strong alliances with members of that faction. This, in part, led Baxter’s 1872 electoral opponent, Joseph Brooks, to challenge Baxter’s right to hold the governorship, thus resulting in the political and military conflict known as the Brooks-Baxter War. For some time, the Brooks-Baxter War involved bipartisan alliances on both sides. Each faction boasted Republican as well as conservative Democratic support. While Brooks had enjoyed support from many Conservatives during the gubernatorial election of 1872, other Conservatives such as Augustus Garland had not forgotten how “radical” Brooks had been during the 1868 constitutional convention. Garland, a Whig before the war and a former Confederate senator, befriended Governor Baxter. This relationship helped usher in the “redemption” of Arkansas.

President Ulysses S. Grant intervened on May 15, 1874, choosing to support Elisha Baxter for governor, while appointing Joseph Brooks postmaster of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Baxter subsequently acquiesced to conservative Democratic demands and called for a new constitutional convention. In June, voters of Arkansas overwhelmingly agreed to call a new constitutional convention by a vote of 80,259 to 8,547. Baxter made this vote possible by working with Democrats to remove the “Iron-Clad” oath; this oath had prohibited most former Confederates from voting in the state. The work of “redemption” had begun, and Democrats captured seventy of the ninety-one seats in the convention. Delegates began their work on July 14, 1874, and the convention continued until September.

The “redeemers” drafted a constitution that rolled back most actions taken by the Republicans since 1868. Provisions dealing with citizenship and race were left intact, but Democrats changed the terms of office for the governor and other constitutional offices from four years to two. They limited the powers and reduced the salary of the governor, and, under the new framework, it only took a simple majority to override a gubernatorial veto. Under the 1874 constitution, almost all officials would be subject to popular elections. Previously, the governor had the power to appoint people to many of these positions.

Democrats not only made changes to the executive branch, but they also limited the government’s ability to raise revenue. The constitution limited the rates at which taxes could be levied. This would eventually hamper the ability of local and state government to provide basic services such as education and infrastructure. Much of this action was in response to what the public and Democratic leaders saw as abuses of the tax system by Reconstruction Republicans.

The voters of Arkansas approved the new constitution on October 13, 1874. In the same election, they elected officials to serve under the terms of the constitution; the Democratic Party won control of both houses of the legislature and the constitutional offices. Augustus Garland, a member of the planter elite, was elected governor. This class had seen its fortunes diminish during the war, and now it was back in control in Arkansas and determined not to lose its position. According to historian Carl Moneyhon, “The return of the Democrats in 1874 for all practical purposes restored Arkansas to those who had dominated it before the war.”

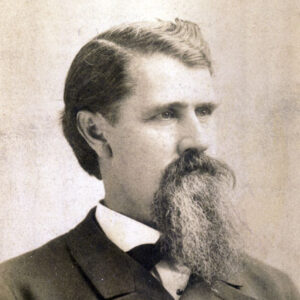

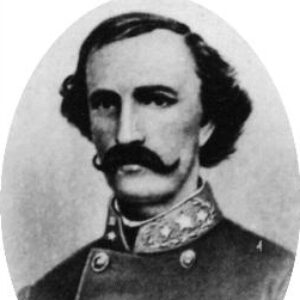

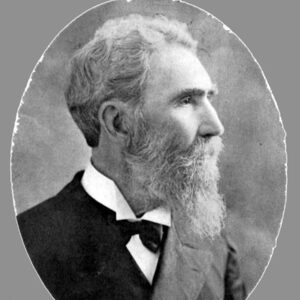

Men such as Garland, former Confederate major general Thomas Churchill, James Henderson Berry, and former lieutenant colonel James Eagle would dominate Arkansas politics into the foreseeable future. These “redeemers” ushered in a time of weakened governmental power, diminished services (such as education), and little governmental sponsorship of internal improvements. What programs the government did enact were sponsored at a lower level than the Republican government had previously. Railroad construction continued, and schools were funded but not at the same level. These leaders represented the state’s landed interests by keeping property taxes low and preserving the status quo. The Arkansas government thus often worked to prevent progressive change. “Redemption” in Arkansas brought mixed results; the unpopular Republicans were pushed out of office, returning the state to the Democratic fold, but in doing so, the Democrats set the stage for Arkansas’s anemic economic growth in the decades to come.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Harris, Rodney W. “Outsiders, Scalawags, and Spendthrifts: The Ideological Battle for Post Civil War Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Central Arkansas, 2011.

Moneyhon, Carl H. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Rodney Harris

Pocahontas, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 James Berry

James Berry  Thomas Churchill

Thomas Churchill  James Eagle

James Eagle  Augustus Garland

Augustus Garland

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.