calsfoundation@cals.org

Native American Rock Art

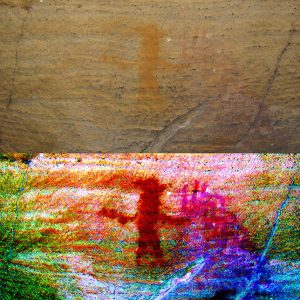

Rock art is a term archaeologists use to describe images on rock surfaces created both prehistorically and historically. Arkansas has one of the richest concentrations of rock art in eastern North America, primarily in the Ozark and Ouachita mountain areas of the state, with a concentration in the central Arkansas River Valley. Rock art has also been discovered along the Mississippi River escarpment toward the eastern part of the state. Most rock art is found in bluff shelters, but it also occurs on exposed boulders, bedrock outcrops, and in caves. Along with the other archaeological resources in the state, rock art is important to understanding the lives of Native Americans living within the region during the pre-colonial era.

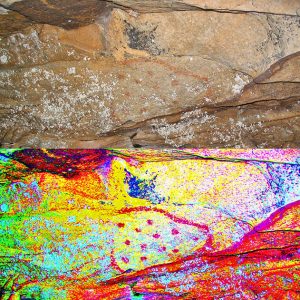

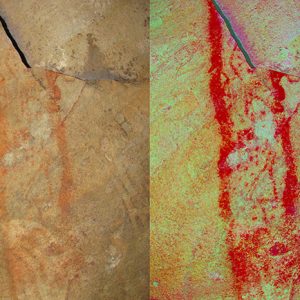

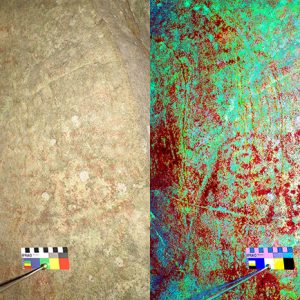

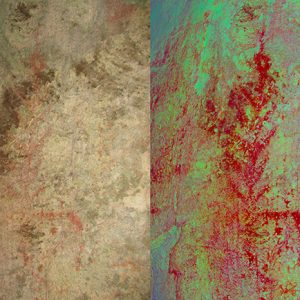

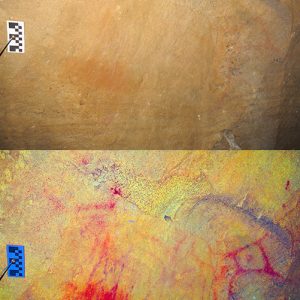

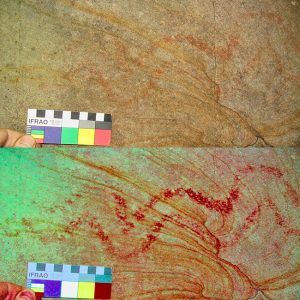

Rock art generally occurs as paintings (pictographs) and carvings (petroglyphs). Applying a pigment to the rock surface either with a tool such as a brush or with fingers created pictographs. Most of the pictographs in Arkansas appear to have been created with the latter method. Petroglyphs were incised or engraved using a sharp stone or other tool or were created by pecking to remove bits of the rock surface to create an image. The information rock art provides is similar to the information other types of artifacts provide, informing archaeologists about plants, animals, or objects Native Americans considered important in their lives. Rock art is often considered to be a ceremonial or ritual artifact, so it can also give clues to spiritual aspects of Native American life.

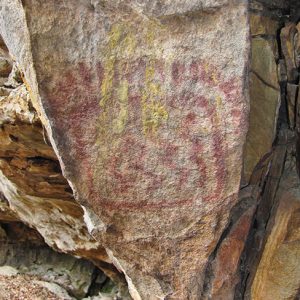

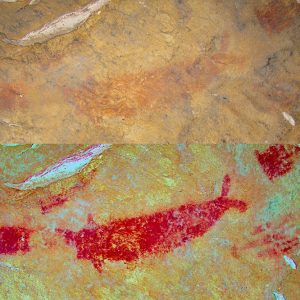

Most rock art images can be classified into three general categories: human or human-like figures (called anthropomorphs or anthropomorphic images); animal figures or representations (called zoomorphs or zoomorphic images); and inanimate objects, symbols, or shapes (usually lumped into one category called geomorphic images). Anthropomorphic images may be standing figures or stick figures, as well as hand- and footprints. Zoomorphic images are not abundant in Arkansas, but recorded images do include an otter, a beaver, a fish, snakes, insects, and animal prints such as deer prints, turkey tracks, and bear paws. Geomorphic images are the most common form in Arkansas and include sunbursts, plant images, lines, swirls, and circles.

The majority of the rock art in Arkansas consists of red pictographs, although yellow and black examples have also been recorded. The central Arkansas River Valley, particularly Petit Jean Mountain near Morrilton (Conway County), has a concentration of red pictographs all painted in a very similar style. These pictographs include images of sunbursts, plants, Native American headdresses, animals, and many geometric shapes. One interesting pictograph is a life-size painting of a paddlefish (spoonbill catfish), possibly indicating the importance of this fish as a food resource to the Native Americans who lived on or near Petit Jean Mountain. Other examples of rock art in Arkansas include carvings of human figures with headdresses, often standing with their arms raised above their head or with bent elbows and hands pointing downward, both common positions found in rock art figures and thought to represent a shamanistic pose.

The age of the rock art in Arkansas is unclear. Modern dating techniques may be able to determine the date of the pigments used to create pictographs, but at this time, researchers have been unable to determine the age of specimens in Arkansas. Based on stylistic comparisons to other types of Native American artifacts, researchers believe most of the prehistoric rock art in the state was probably created during the Mississippian Period (approximately AD 900–1600). Excavations at one site in northwest Arkansas uncovered tools that were used to create the rock art there. Other artifacts (carbonized material) associated with these tools date to about AD 1495, suggesting that the rock art, which includes a large panel of over twenty human figures in a procession led by one larger figure wearing a headdress and carrying a staff, was made around that time.

The first published account of rock art in Arkansas was in the Smithsonian Institution’s “Annual Report for 1881,” although undoubtedly Arkansas residents were aware of the rock art before this time. In 1922, Mark Raymond Harrington of the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation visited and recorded sites in northwest Arkansas. In the 1930s, Winslow Walker recorded rock art in Arkansas for the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology. S. C. Dellinger of the University of Arkansas Museum was the first major researcher in the state to focus on the rock art, also in the 1930s. Also around this time, T. W. Hardison and Raymond H. Torrey recorded the rock art on Petit Jean Mountain. This rock art likely inspired Hardison to establish the state park on the mountain.

Historic settlers and visitors to Arkansas sometimes left drawings or inscriptions on rock surfaces. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) were active in Arkansas in the early part of the twentieth century and played a role in the building of many of Arkansas’s state parks. Carvings left by members of these groups and other historic settlers to the state have been recorded as historic rock art. Modern inscriptions (often left with spray paint over prehistoric rock art), however, are not considered rock art but rather vandalism. Vandalism continues to be the biggest threat to rock art sites. While locations of sites are not public record, many rock art sites are on state or federal land and have become well-known places to visit. These “visits” often include looting and vandalism. Measures, such as posting of educational material and signs, have been taken at these publicly accessible sites, but preventative measures—such as video cameras, guarding the sites, and/or gating the sites—are usually cost prohibitive. In the early 1980s, twenty-eight Arkansas rock art sites were listed on the National Register of Historic Places under a thematic nomination—the first thematic nomination of this type in the country. Unfortunately, being listed on the National Register still does not protect the sites from vandals.

For additional information:

Diaz-Granados, Carol, Jan Simek, George Sabo III, and Mark Wagner. Transforming the Landscape: Rock Art and the Mississippian Cosmos. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 2018.

Hilliard, Jerry, Gayle Fritz, and Eben S. Cooper. The Archeology of Rock Art at the Narrows Rock Shelter, Crawford County, Arkansas. Research Report No. 31. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2004.

Rock Art in Arkansas. http://arkarcheology.uark.edu/rockart/index.html (accessed April 16, 2021).

Sabo, George III, and Debora Sabo, eds. Rock Art in Arkansas. Popular Series No. 5. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2005.

Schaefer, Jordan. “Decisions Set in Stone: Spatial Analyses of Ozark Rock Art Sites, Elements, and Motifs with GIS.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2018.

Michelle Berg-Vogel

West Fork, Arkansas

Historical Archaeology

Historical Archaeology Petit Jean Rock Art Sites

Petit Jean Rock Art Sites Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540

Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540 3CN125 Rock Painting

3CN125 Rock Painting  3CN126 Pictograph

3CN126 Pictograph  3CN128 Pictograph

3CN128 Pictograph  3CN130 Graffiti

3CN130 Graffiti  3CN130 Petroglyph

3CN130 Petroglyph  3CN132 Site Painting

3CN132 Site Painting  3CN168 Painting

3CN168 Painting  3CN17 Pictograph

3CN17 Pictograph  3CN17E20 Rock Painting

3CN17E20 Rock Painting  3CN20 Rock Painting

3CN20 Rock Painting  3CN20 Rock Painting

3CN20 Rock Painting  3CN304 Pictograph

3CN304 Pictograph  3CN32 Rayed Circle Pictograph

3CN32 Rayed Circle Pictograph  Aboriginal Rock Art

Aboriginal Rock Art  Concentric Circles at 3CN17

Concentric Circles at 3CN17  Pictograph at Site 3CN20

Pictograph at Site 3CN20

The Crow Mountain Petroglyphs were first attributed to Native Americans, then the Vikings, but a recent study suggests that they were carved by the clergy who accompanied de Soto. De Soto retreated to this area after an ill-fated skirmish with the Tula Indians. He overwintered in this area and licked his wounds. (Carrion) Crow Mountain is a mesa-like mountain where he found refuge and could graze his remaining horses and pillage the gardens of Carden Bottoms, just south of there. Skip Stewart Abernathy found relics of the period there.

The carvings were done by educated men, probably the clergy, Cistercian monks. They are aligned with the North Celestial Pole. The Eucharist was important at that time. The circle in the center is the symbol for the Knights Templar. Somebody in recent history has tried to make it into a peace symbol.

The three holes below the circle represent the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The “V” shaped symbol at the bottom is “the cup” or grail. Parallel lines at the top are unexplained.

The petroglyphs are on private land, but people are invited to visit them. A “bluff shelter” is located across the creek from the petroglyphs.

Donald E. Rickard

Professor Emeritus of Physical Science at Arkansas Tech University