calsfoundation@cals.org

Olyphant Train Robbery

During the nineteenth century, travelers on steam locomotives were at risk for train robberies. In Arkansas, one particularly high-profile train robbery happened in the small town of Olyphant (Jackson County) in 1893. What followed was a sensationalized manhunt and the execution of three bandits involved in the incident.

On November 3, 1893, the seven-car Train No. 51 of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway pulled off to a side track so that the Cannonball Express, a much faster train, could pass. It was about 10:00 p.m. on a cold and rainy night; the train had left Poplar Bluff, Missouri, at noon that day and was headed to Little Rock (Pulaski County). Many of the 300 passengers were wealthy tourists who were coming back from the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, which had closed on October 30. Its stop was made in the small town of Olyphant, about seven miles south of Newport (Jackson County). The Irish-born conductor, William P. McNally, had been making the Poplar Bluff to Little Rock trip since the early 1880s, and his outgoing personality made him very popular on the route. At the time of the robbery, he was planning to be retired by the end of the month.

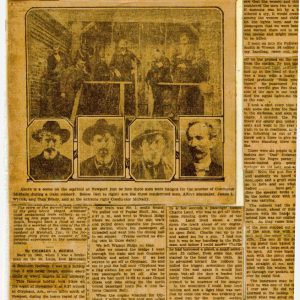

While No. 51 was stalled, a group of bandits took the opportunity to rob it. Gunshots rang out, and the baggage attendant rushed to McNally, warning of a holdup. McNally immediately went through the passenger cars, advising everyone to hide their valuables. He also borrowed a gun from a passenger named Charles Lamb and retreated to the front of the train. The bandits eventually made their way to the front of the train, stopping to rob the passengers; the net value of what they stole reached $6,000. When they reached the front of the train, McNally fired at them, and one of the men shot him with a rifle. After a twenty-minute hold-up, the bandits made their getaway, and, once they were gone, the train made it to Little Rock. By that time, however, McNally was dead from his gunshot wounds.

In the following days, sheriffs from ten counties pulled together posses to search for the bandits, for whom a large reward was offered. The St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway had published an offer of a $300 reward, and both the Pacific Express company and Governor William Fishback had also promised rewards, though the amount was not specified. Because McNally was such a beloved character in the railroad business, thousands attended his funeral, and a statewide fervor to find the perpetrators took hold. The ensuing manhunt created a media sensation; many “suspicious” characters were arrested and harassed all over Arkansas, and the Arkansas Gazette’s coverage of the incident filled the entire front page. There were frequent reports of near-captures and exciting gunfights with suspects as the sheriffs and their posses combed the hills for the robber gang.

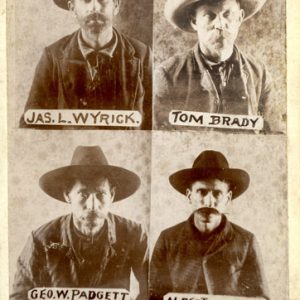

By December 1893, four major suspects had been rounded up: Tom Brady, Jim Wyrick, Albert Mansker, and George Padgett. Rather than leave the state or adopt aliases, all of them had remained within a fairly close range of the scene of the crime. The first three were tried in January 1894; all were convicted of first-degree murder for the death of McNally and were sentenced to execution by hanging. Because of his service as a witness, Padgett was not given the death penalty.

During the trial, the robbers’ plan was exposed by Padgett, who was the main witness against the other four. The four had met in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) while peddling whiskey, and it was Padgett and Brady’s idea to rob a train. Rendezvousing at a railway station near Searcy (White County), they made plans to rob the Cannonball Express, which had cash and gold from the Federal Reserve Bank, in what they convinced each other was a get-rich-quick scheme. Only Mansker had a history of train robbing. Padgett took a ride on No. 51 and learned that it stopped in Olyphant, both to drop off mail and to allow another scheduled train to pass. Hearing that “a bunch of rich folks from Chicago” would be riding on it, the prospective thieves changed their plans, and No. 51 became the target. For a few days before the robbery, they had ridden their horses up and down the track, reconnoitering, until the night of the robbery finally came. Beforehand, they all had drunk heavily to calm their nerves.

Brady, Wyrick, and Mansker were hanged on April 6, 1894, outside of the city jail in Newport. Before the hanging took place, they were allowed to address the crowd, and all three claimed innocence for the murder.

For additional information:

Hipp, Joe Wreford. Legacy of a Robbery on the Iron Mountain Railroad. Little Rock: Renegade Press, 1996.

Luker, Lady Elizabeth. “The Olyphant Train Robbery.” Stream of History 18 (November 1981): 2–12.

Morrow, John P., Jr. “The Olyphant Train Robbery.” Independence County Chronicle 2 (October 1960): 3–14.

“Olyphant Train Robbery: Contemporary Newspaper Reports.” The Mansker Chronicles. http://www.mansker.org/history/olyphant.htm (accessed March 15, 2022).

Bernard Reed

Little Rock, Arkansas

Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Olyphant Train Robbers

Olyphant Train Robbers  Olyphant Train Robbers Execution

Olyphant Train Robbers Execution  Olyphant Train Robbers Execution

Olyphant Train Robbers Execution  Olyphant Train Robbery Account

Olyphant Train Robbery Account

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.