calsfoundation@cals.org

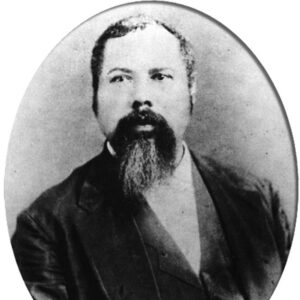

Moses Aaron Clark (1834–1924)

Moses Aaron Clark rose from slavery to become one of the most successful African American Arkansans of his time. Elected as a Helena (Phillips County) alderman during Reconstruction, Clark became a lawyer and was one of Arkansas’s first Black justices of the peace. After Reconstruction, Clark became arguably the most important Black Masonic leader in Arkansas. For more than a quarter of a century, he led the Arkansas Prince Hall Free and Accepted Masons, one of the oldest and most prestigious African American fraternal orders. He was also a major Masonic figure on the national stage. As a prosperous Lee County real estate owner, planter, and businessman during the post-Reconstruction era, for forty years, Clark reached statewide audiences through annual travels and speeches in all parts of the state and through the Opinion-Enterprise, one of the state’s leading African American newspapers.

Clark was born a slave near Germantown, Tennessee, on August 15, 1834. His father was white slaveholder George Clark Jr., and his mother was young slave named Maria. In 1849, George Clark Jr., began farming at Cotton Plant (Woodruff County) and brought Moses Clark with him. However, in 1856, George Clark Jr. died, and his siblings sold Moses Clark at auction on January 10, 1857. Stephen W. Childress, attorney general for the First Judicial District of Arkansas, bought Clark to serve as his valet, sending Clark to Helena to James M. Alexander to learn the barbering trade the following year. While still a slave, Clark began a process of self-education in which he learned to read and write. Freed during the Federal occupation of Helena, Clark followed the Union army into Tennessee, but returned to Helena after the Civil War.

In 1866, Clark became one of the first Black business owners in Helena by opening a barbershop in partnership with Isaac Coursey, a freeborn Black man from Ohio. A few years later, Clark opened the first of seven stores he would eventually own. In 1870, Clark married his business partner’s daughter, Georgia Anna Coursey; eleven of their children survived to adulthood. Clark married Louisa Latham several years after his first wife’s death.

During the decade of the 1870s, Clark passed the bar examination and was elected as alderman in Helena. In 1871, Clark was elected justice of the peace, thus becoming one of the first African Americans elected to the judiciary in Arkansas; he served until 1880. Justices of the peace at the time had jurisdiction to decide misdemeanor cases and some civil matters. Clark also was a witness before the Southern Claims Commission, giving testimony regarding the claims for reimbursement for property taken by the Union forces during the Civil War. In an 1877 hearing, Clark testified against Laura O’Conner, Confederate general Thomas Hindman’s stepmother, who claimed that she was a Union sympathizer in an effort to secure reimbursement.

The following year brought a harsh wave of violence and terrorism to Phillips County aimed at seizing political control from Republicans, both Black and white. Democrats, who faced a large Black Republican majority, targeted Republican leaders such as Jacob Trieber and Henry M. Cooper and used mob violence at the polls to stop Black voters. They destroyed supplies of Republican ballots and intimidated Republican poll-watchers. In addition, militia groups like the Helena Rifles formed to imitate the Mississippi Redshirt Movement. These acts of violence and intimidation may well have ended Clark’s political career in Phillips County and influenced his decision to move to Marianna (Lee County) in 1880.

In Marianna, Clark opened another barber shop and became a partner in a large farm. He eventually owned six stores as well as several buildings on Main Street, including a large house at the corner of Main and Clark streets, the latter street named in his honor. Clark founded the Opinion-Enterprise (1907–1922?), which became one of Arkansas’s leading Black newspapers. He accumulated wealth through investments in real estate and the stock market.

In 1884, Clark was an at-large member of the Arkansas delegation to the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. Later, Clark joined the Democratic party and in 1894 ran in the primary elections for state representative. By then, so many Black voters had been disenfranchised that Clark lost the race to William L. Howard, a white candidate. During the campaign, the Lee County Courier spoke highly of Clark, stating that he “makes one of the most sensible talks that is made in the canvass. Clark is a plain, practical, sensible man, and an orator besides. He knows how and what to talk about and makes no hesitation in doing so.”

Beginning in 1866, Clark had a long and successful career as a Mason. In 1887, Clark chaired the National Masonic Congress in Chicago, Illinois. His several terms as the Arkansas grand master spanned 1881 to 1905. Under Clark’s leadership, the number of Prince Hall lodges grew from thirteen to 300. Membership increased from 300 to 6,000 of Arkansas’s most influential African American men. Clark addressed audiences in all parts of the state where Black people lived, as well as to a few lodges in Indian Territory. Under Clark’s leadership, the Arkansas Prince Hall Masons built a four-story Masonic temple in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and created one of the first safety nets for Black residents by paying for their medical treatment, providing them with life insurance, assisting victims of natural disasters, securing and funding legal redress for them in the courts, and working to enable them to avoid the hazards associated with sharecropping.

Clark as was conservative rather than radical in his opinions. At first he advocated staying in Arkansas as the best route toward economic progress for the state’s African Americans. However, by 1906, lynching and other widespread forms of violence against African Americans led Clark to abandon that position. Of some of his contemporaries who were relocating to California, he wrote, “I could not advise them not to go. Seeing things as they are here, I was only sorry that my affairs were in such a condition that I could not be in the exodus.”

Clark’s views on economic progress were very similar to those of Booker T. Washington with one great exception: Clark believed that pursuing elective politics was just as necessary as economic progress. Ironically, Booker T. Washington’s followers John Bush and S. T. Boyd led the effort to oust Clark as grand master. Clark had resisted Bush’s efforts to advance his political career by co-opting the Prince Hall Masons, then seen as a rival to Bush’s Mosaic Templars of America. Although ousted as grand master, Clark later served as treasurer of the Prince Hall Masons and in leadership roles in other Masonic groups.

Clark died on April 10, 1924, in Marianna. His grave is in the Magnolia Cemetery in Helena. The Indianapolis Freeman described Clark as “universally recognized as one of the most enterprising, intellectual and useful men in the state of Arkansas.” The Chicago Daily News described him as “stalwart in frame, erect and dignified in carriage” and an “admirable presiding officer.” The Pine Bluff Weekly Graphic praised him as “one of the most remarkable men of his race in the southland.”

For additional information:

Apple, Nancy, and Suzy Keasler, eds. History of Lee County, Arkansas. Dallas, TX: Curtis Media Group, 1987.

Centennial Souvenir: 100 Years of Freemasonry, 1872–1972, M. W. Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Jurisdiction of Arkansas, August 6–9, 1972. Pine Bluff, AR: Grand Masonic Temple, 1972.

Hamilton, Green Polonius. Beacon Lights of the Race. Memphis: E. H. Clarke & Brother, 1911.

Holman, Charles. Moses A. Clark Family in History of Lee County, Arkansas. Edited by Nancy Apple and Suzy Keasler. Dallas, TX: Curtis Media Group, 1987.

Kilpatrick, Judith. Arkansas’ Early African-American Lawyers: A History. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas School of Law, 2002.

“M. A. Clark.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana). March 2, 1889, p. 1.

“M. A. Clark, Colored, Candidate for Representative of Lee County.” Lee County Courier. August 4, 1894, p. 2.

Muraskin, William A. Middle-Class Blacks in a White Society: Prince Hall Freemasonry in America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual Communication of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge, F. & A. M. of the State of Arkansas. Pine Bluff, AR: Pine Bluff Herald Power Print, 1902.

Russel, Marvin Frank. “The Republican Party of Arkansas: 1874–1913.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1985.

Kathryn C. Fitzhugh

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law

Charles F. Holman

Baltimore, Maryland

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Moses Clark House

Moses Clark House  Georgia Clark

Georgia Clark  M. A. Clark

M. A. Clark

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.