calsfoundation@cals.org

Vanadium Mining

Major deposits of vanadium were discovered in central Arkansas by Union Carbide’s Western Exploration Group in the 1960s. Vanadium orebodies are found in two isolated igneous intrusive complexes in the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas: the Potash Sulphur Springs (now Wilson Springs) complex located in Garland County and the Magnet Cove complex in Hot Spring County. The Wilson Springs vanadium deposits were the first to be mined solely for vanadium in the United States.

The major use of vanadium is as an alloying metal in iron and steel (ferroalloy). Small amounts of vanadium added to iron and steel significantly increase its strength, improve toughness and ductility, and reduce weight, making it suitable for structural and pipeline steel. Vanadium also increases high-temperature abrasion resistance of steel, a desirable property for die steels and high-speed tool steels used at elevated temperatures. Other uses for vanadium include manufacture of stainless and surgical steels and specialty nonferrous aluminum, titanium, and tungsten alloys. Compounds of the metal are also used by the chemical industry as a catalyst in the manufacture of sulfuric acid and organic compounds; to make resins and plastics; and as a coloring agent in glass, ceramic glazes, and enamels.

The discovery of anomalous radioactivity at Potash Sulphur Springs motivated a study in 1950. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Atomic Energy Commission, the Arkansas Geological Commission (now the Arkansas Geological Survey), and various public interests explored the area. Although no significant amounts of uranium were discovered, geochemical analyses of samples by the USGS disclosed significant quantities of niobium and vanadium in the uranium prospect. The USGS also investigated the potential for titanium and niobium at nearby Magnet Cove. Several papers written about the titanium deposits revealed the potential for niobium and vanadium in Garland and Hot Spring counties. Union Carbide geologists first investigated the Wilson Springs property for vanadium in 1960. Core drilling in 1961 and 1962 resulted in discovery of vanadium ores. Vanadium was also discovered in the Christy brookite (titanium) deposit on the east side of the Magnet Cove intrusion. Final drilling in 1964 and 1965 proved to have sufficient reserves to justify construction of the Wilson Springs vanadium mill.

Four separate orebodies were discovered at Wilson Springs—East Wilson, North Wilson, Spaulding, and T-Orebody—but only the East Wilson and North Wilson pits were mined for mill processing. The Spaulding and T-Orebody were partly developed. Pit wall instability challenged mining the Spaulding. Poor mill feed quality affecting vanadium recovery was disclosed in the T-Orebody, and further development was terminated. Preparation of the Wilson Springs property for mining began in 1966 with development of the North Wilson Orebody. East Wilson mine development was initiated around 1967 or 1968. They provided the major ore feed for the Wilson Springs vanadium mill throughout its sporadic production history. A test pit was initially developed in the Christy deposit for metallurgical testing. Later, additional ore was mined and processed at the mill. Christy mine feed was minimal. The East Wilson and North Wilson mines produced 4.75 million short dry tons (sdt) of vanadium ore that averaged 1.20 percent vanadium pentoxide (V2O5) mine grade. Waste production was about 13.4 million sdt.

In 1966, Union Carbide began mining operations and stockpiling vanadium ore in Garland County. Construction of the vanadium processing mill was completed in 1967, and vanadium oxide was produced for the first time in Arkansas in 1968. By 1970, Arkansas was a major vanadium-producing state in the nation. Records show that Arkansas was second to Colorado in 1971 and then led the nation in vanadium production for six consecutive years until the mill was idle for about eight months in 1978 due to a decline in demand. Operations resumed in early 1979, but Arkansas dropped to third in the nation. Productivity declined in 1980 due to a seven-month shutdown for mill maintenance, and lack of demand dropped Arkansas to fourth of five producing states in the nation. Production continued in 1981, and the state ranked fourth of the six producing states. The mine and mill were closed indefinitely in 1982 and remained on standby through 1983. Facilities were reopened in July 1984 and operated at capacity for the remainder of the year.

The orebody geometries were funnel-shaped to pipe-like. The deposits, exposed at the surface on steep hill slopes, were an ideal shape for open-pit mining. The mill was capable of processing 1,600 tons of ore per day, using conventional salt roast-water leach methods. Ore quality and grade were the two main factors required for mill feed amenability. Quality not only depends on the amount and type of clays but also on certain elements and minerals in the ore that cause roasting problems and low vanadium recovery. Amenable mill feed was achieved by blending and diluting problem ores with “good” ores. Mill feed stockpiles were a mix of East Wilson high-clay ore and North Wilson low-clay ore at a ratio of 70:30 that averaged 1.00 percent V2O5. Purchased high-grade vanadium material was added to stockpiles to increase feed grade. The end product of the ore processing was shipped to Union Carbide’s plant in Marietta, Ohio, and converted to carbon-vanadium briquettes (CARVAN) used by the steel industry to make specialty vanadium alloy steels.

A test pit was excavated at the Christy Mine in 1975 for the purpose of metallurgically testing the economic recovery of vanadium from the ore. The lab tests to recover the vanadium were successful by 1976. Additional pit development was conducted in 1981 and again in 1984 after reopening of the mine and mill facilities in July. Stockpiled ores were stored at the mine site until needed for future mill feed.

The Mining and Metals Division of the Union Carbide Corporation created Umetco Minerals Corporation in 1984, a wholly owned subsidiary of Union Carbide. The mill resumed operation in 1985 but became idle in 1986. Variable mine production and mill output were typically caused by fluctuating vanadium prices, competitive worldwide vanadium production, domestic steel production, and reduction in consumer inventories. In May 1986, the mill and facilities were sold to U.S. Vanadium Corporation, wholly owned by Strategic Minerals Corporation (STRATCOR). Union Carbide retained rights and environmental responsibilities to the mining property. The STRATCOR mill processed ore for Union Carbide from the North Wilson and Christy mines for a short time. Ore that remained in the North Wilson pit from Union Carbide mining was moderate grade but low in clay content. Therefore, enough high-clay ore from the Christy mine was blended with it to achieve an amenable mill feed until the ore was depleted from the North Wilson mine.

STRATCOR bought the vanadium facilities from UMETCO early in 1986. The company brought the mill back into operation late in the year and processed purchased materials through 1987. STRATCOR resumed operation of the vanadium-roasting facility in 1988 to feed previously stockpiled ore and purchased materials. The Wilson Springs and Christy mines were reopened in 1989 after a four-year closure. Mining activities were again shut down in 1990. Stockpiled and newly mined Christy ores were processed with Wilson Springs ores that year. STRATCOR continued operation of the nation’s only vanadium mill in 1990, but the mines were not worked and are now closed. Since Wilson Springs and Magnet Cove orebodies are the only economically exploitable vanadium deposits in Arkansas, vanadium mining in the state terminated with the closing of the mines in 1989.

The economic impact of vanadium mining was significant to Garland County and Arkansas as a whole. Union Carbide invested $14 million developing the Wilson Springs mining and milling complex. The facilities were dedicated on May 20, 1967. More than eighty percent of the workforce was drawn from the Hot Springs (Garland County) area, with an annual payroll of more than $1 million. In 1979, operations resumed after an eight-month shutdown with a full employment of 240 people. The facility was projected to have a $16 million impact on the area during 1979, including payroll, purchases, and taxes.

Reclamation of the Christy mine in order to restore the land began after October 1, 1996, when UMETCO renewed their mine reclamation permit with the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality, Surface Mining and Reclamation Division (ADEQ-SMRD). Reclamation was completed, and the Christy Mine was fully reclaimed by September 23, 1997.

The Wilson Springs mine reclamation started after an October 1, 1997, meeting between Umetco and ADEQ-SMRD to discuss starting the project. The reclamation is ongoing. Actually, some reclamation was initiated in 1969, at which time Union Carbide began reclaiming waste-dump areas that were created during the initial 1966 mine development. Grass and pine trees were planted to stabilize the surface and slopes and minimize erosion.

For additional information:

Beroni, E. P. “Maps of Wilson’s Prospect, Garland County, Arkansas.” 1955. On file at Arkansas Geological Survey, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Bureau of Mines Minerals Yearbooks, 1966–1991. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/usbmmyb.html (accessed March 15, 2022).

Fryklund, V. C., Jr., R. S. Harner, and E. P. Kaiser. “Niobium (Columbium), and Titanium at Magnet Cove and Potash Sulphur Springs, Arkansas.” In U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1015-B. Washington DC: U.S. Geological Survey, 1954.

Fryklund, V. C., Jr., and D. F. Holbrook. Titanium Ore Deposits of Hot Spring County, Arkansas. Bulletin 16. Little Rock: Arkansas Resources and Development Commission, Division of Geology, 1950.

Hollingsworth, J. S. “Geology of the Wilson Springs Vanadium Deposits, Garland County, Arkansas.” In Field Trip Guide Book, Central Arkansas, Economic Geology and Petrology. Little Rock, Arkansas Geological Commission, 1967.

Howard, J. M., and D. R. Owens. “Minerals of the Wilson Springs Vanadium Mines, Potash Sulphur Springs, Arkansas.” Rocks and Minerals 70 (May/June 1995): 154–170.

Taylor, I. R. “Union Carbide’s Twin-Pit Vanadium Venture at Wilson Springs.” Mining Engineering, April 1969, 82–85.

Owens, Don R. “Vanadium Mining in Garland County.” The Record 49 (2008): 205–207.

Don R. Owens

UALR Department of Earth Sciences

Business, Commerce, and Industry

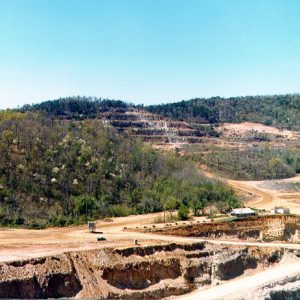

Business, Commerce, and Industry Christy Vanadium Mine Pit

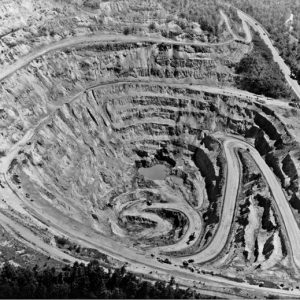

Christy Vanadium Mine Pit  East Wilson Pit

East Wilson Pit  East Wilson Vanadium Mine Pit

East Wilson Vanadium Mine Pit  North Wilson Vanadium Mine

North Wilson Vanadium Mine

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.