calsfoundation@cals.org

Democratic Party

Even for the historically one-party Democratic South, the Democratic Party’s control of Arkansas politics was solid—until the end of the twentieth century. Indeed, from the end of Reconstruction, Republican presidential candidates were denied Electoral College votes every four years until Richard Nixon’s 1972 victory. The Democratic Party’s dominance of state and local elections (outside northwestern Arkansas, which had housed Republicans since the Civil War era) was just as impressive. Still, while Democrats long fended off any sustained Republican development, recent trends–especially the historic results in the 2010, 2012, and 2014 election cycles–indicate that the change that has come to other Southern states with the rise of a competitive Republican Party has taken root in Arkansas.

Before statehood, Arkansas politics was dominated by a small group known by a variety of names, most commonly “The Family.” This Johnson-Conway-Sevier-Rector cousinhood accumulated 190 years of public office-holding, including two U.S. senators and three governors in antebellum Arkansas; other offices went only to their partisans. Because the Family was allied with President Andrew Jackson, Arkansas began its political life dominated by the Democratic Party. The opposing faction, which almost by default became associated with the Whigs, at times generated rather spirited opposition. Still, no one but a Democrat won the presidential or gubernatorial election in Arkansas in this era, and the only Whig elected to Congress, Thomas W. Newtown, filled several weeks of an unexpired term opened by Archibald Yell’s resignation from the office in 1846.

During the Reconstruction era, a series of Republicans held the state’s preeminent political offices, but the norm of Democratic rule returned immediately after Reconstruction’s end in 1874. These “redeemers” shared a generally noninterventionist view of state government, with taxes, appropriations, and regulations kept to a minimum. Frustration about the nonresponsiveness of government grew among farmers in the mid-1880s, as revealed by the growth of populist organizations such as the Farmers’ Alliance and the Agricultural Wheel. Republicans eventually recognized in their growing numbers an opportunity to recapture power. In 1888, they nominated no candidate of their own but instead backed Charles M. Norwood, gubernatorial candidate of the dissident Union-Labor Party. While Democrat James P. Eagle defeated Norwood by about 15,000 votes, this genuine competition alarmed Democrats. In response, the political establishment saw to the enactment of a series of electoral “reforms,” i.e. disfranchising measures, that emasculated the opposition and forced the emerging populistic temper to participate within a one-party and generally issueless mold for the next six decades.

The Democrats elected as the state’s delegates in the U.S. House and Senate were typically not challenged vigorously after being elected. As a result, these incumbents built up tremendous power in legislative bodies where seniority was highly valued. Senator Joe T. Robinson (who became Democratic majority leader), Congressman Wilbur D. Mills (who became chair of the Ways and Means Committee), Senator J. William Fulbright (longtime chair of the Foreign Relations Committee), and Senator John L. McClellan (father of the McClellan-Kerr dam system) exemplify the power that the state had in Washington DC during this era.

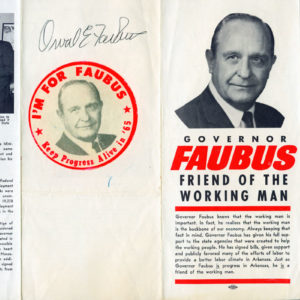

While the first half of the twentieth century witnessed factionalized and chaotic battles in Democratic primaries for state offices, especially for the governorship, Governor Orval Faubus developed a dominant machine after his initial election in 1954. Faubus, who gained national notoriety for his attempts to block the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957, used this powerful organization to gain an unprecedented six terms in office. But he could not transfer his personal organization to other Democrats when he decided to retire in 1966, having appointed every member of every state board and commission. (Faubus later made three failed comeback attempts.)

In 1966, the Democratic Party lost the governorship for the first time in the modern era. But the Republican candidate, Winthrop Rockefeller, differed dramatically from those in his party who began to be elected in other Southern states. Rockefeller was a racial liberal who developed a coalition of progressive Democrats disenchanted with the conservative Faubus machine, newly enfranchised African Americans, and traditional Republicans to gain the office and reelection in 1968 over Faubus protégés. Despite his electoral successes, Rockefeller failed to work successfully with the almost totally Democratic legislature and could not advance his agenda.

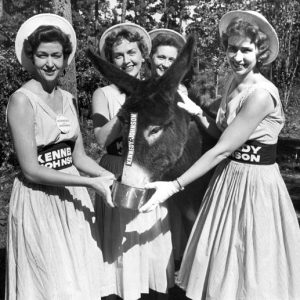

In 1970, the Democrats nominated for governor the unknown but telegenic progressive Dale Bumpers rather than Faubus. Thus began a new era of dominance for the Democratic Party as its progressives returned home in Bumpers’s easy victory over Rockefeller in the general election. Black voters followed in subsequent elections, leaving the Republican Party in its traditional and feeble role, except in the state’s northwest corner. In many elections, Democrats—who spanned the ideological spectrum—won office without Republican opposition.

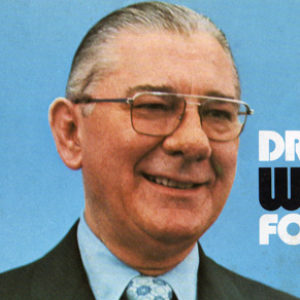

Bumpers was followed to the governorship, and later the U.S. Senate, by another progressive, David Pryor, a personable politician considered by many to be the most popular Arkansas politician of the contemporary era. Pryor served two terms as governor, from 1974 to 1978, before being replaced by a third politician in a similar mold, thirty-two-year-old Attorney General Bill Clinton. Except for the two years after his 1980 upset loss to Republican Frank White, Clinton served as governor until 1992, winning five general elections in a gubernatorial career equaled in tenure only by Faubus.

Bumpers, Pryor, and Clinton—termed by one observer the “Big Three” of modern Arkansas politics—developed separate, yet overlapping, organizations that hampered Republican Party development. No coherent state Democratic organization developed in this period despite the party’s continued electoral success in state and local politics. The culmination of the state’s progressive Democratic era was the elevation of Clinton in 1992 as the first president from the state.

Ironically, this ultimate triumph for the Arkansas Democrats led to the party’s first lasting electoral difficulties in the modern era. Clinton’s victory elevated Lieutenant Governor Jim Guy Tucker, a Democrat, to the top of state government in late 1992; Tucker was elected governor on his own in 1994. However, in a successful prosecution connected to the investigation of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s business dealings in Arkansas (the Whitewater Scandal), Tucker was convicted by a federal jury on a series of charges unrelated to his time as governor in 1996. Waiting in the wings to rise to the governorship after Tucker’s resignation was a Republican—the former president of the state Southern Baptist Convention, Mike Huckabee. Huckabee, coming off a loss for the U.S. Senate to Bumpers in 1992, had won a closely contested special election in 1993 to gain the lieutenant governorship.

Huckabee, who would win his own election as governor in 1998, was the first Republican governor to share some of the personal dynamism of the “Big Three,” suggesting that Huckabee could become an effective proponent of Republican development in the state. The Democrats’s electoral difficulties continued as they lost Pryor’s Senate seat and the lieutenant governorship in 1996. Both losses were historic: the first meant Democrats failed to control both Senate seats from the state since the direct election of U.S. senators commenced, and the second meant that, for the only time outside the Rockefeller era, Democrats held neither the governorship nor the lieutenant governorship.

Democrats enjoyed distinct advantages in Arkansas politics at the legislative and local level as the Republican Party lagged in development and candidate recruitment. Indeed, despite the introduction at the turn of the century of state legislative term limits that shortened the terms of the mostly Democratic incumbents, the Arkansas General Assembly remained one of the most one-party dominated in the country in the first decade of the twenty-first century. A plurality of Arkansans (44.1 % in a 2001 poll) also continued to identify themselves as Democrats.

However, in the 2010 election cycle, despite a landslide win by Democratic incumbent governor Mike Beebe, Arkansas Democrats were shaken by a series of losses that, all together, marked the most successful outing by Republicans since the Reconstruction era. After the election, Republicans controlled one of two U.S. Senate seats, three of four U.S. House seats, three state constitutional offices, and over forty percent of legislative seats. Two years later, Republicans captured a majority in the Arkansas General Assembly for the first time since Reconstruction, as well as sweeping the state’s four spots in the U.S. House of Representatives. Many pointed to Arkansans’ emphatically negative response to President Barack Obama’s presidency, in combination with demographic changes in the state, as key to these shifts. In 2014, the Democratic Party experienced a rout that witnessed U.S. senator Mark Pryor and all four congressional candidates losing to Republican challengers; in addition, the Republican Party solidified its gains in both houses of the Arkansas General Assembly and claimed all of the state’s constitutional offices, becoming the state’s majority party in a direct contrast with most of the state’s political history. Two years later, state Republicans managed to gain a supermajority in the Arkansas House of Representatives following the defection of two Democratic Party members to Republican ranks in the wake of an election that solidified Republican power both nationally and locally. Since then, the Democratic Party has only been able to exercise any political power at the local level in certain parts of the state, particularly urban areas such as Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Fayetteville (Washington County), in addition to certain Delta counties with significant African American populations. Republicans expanded their supermajority in both houses of the state legislature in 2022, Senate Republicans adopted a rule change shortly after the election to limit Democratic representation on committees.

For additional information:

Barth, Jay. “Arkansas: Last Hurrah for a Native Son.” In The 1996 Presidential Election in the South: Southern Party Systems in the 1990s, edited by Laurence Moreland and Robert Steed. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1997.

Barth, Jay, Diane D. Blair, and Ernie Dumas. “Arkansas: Characters, Crises, and Change.” In Southern Politics in the 1990s, edited by Alexander P. Lamis. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999.

Blair, Diane D., and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2d ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Jay Barth

Hendrix College

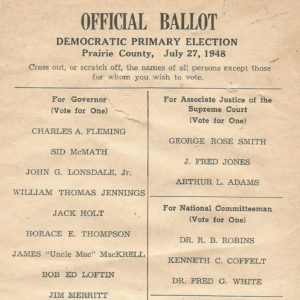

1948 Primary Ballot

1948 Primary Ballot  Dale Bumpers Inauguration

Dale Bumpers Inauguration  Ben Butler with Orval Faubus

Ben Butler with Orval Faubus  James Conway

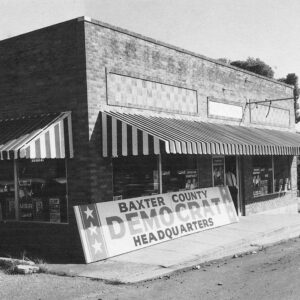

James Conway  Democratic Headquarters in Mountain Home

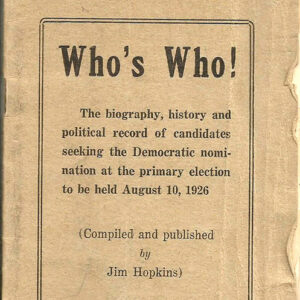

Democratic Headquarters in Mountain Home  Democratic Party Booklet

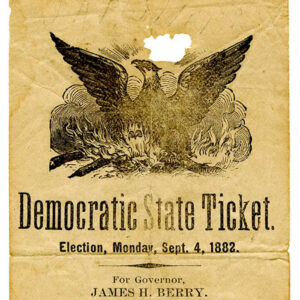

Democratic Party Booklet  Democratic Ticket, 1882

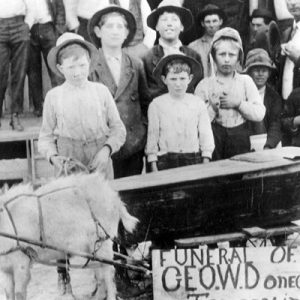

Democratic Ticket, 1882  Donaghey Mock Funeral

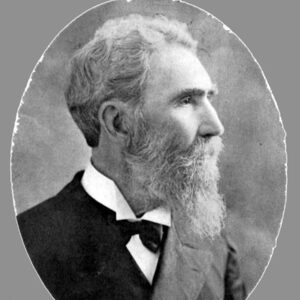

Donaghey Mock Funeral  James Eagle

James Eagle  Faubus Campaign Brochure

Faubus Campaign Brochure  Bill Fulbright

Bill Fulbright  John McClellan

John McClellan  Wilbur Mills Brochure

Wilbur Mills Brochure  Wilbur D. Mills

Wilbur D. Mills  Ozark Frontier Trail Festival

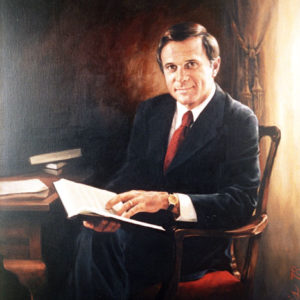

Ozark Frontier Trail Festival  David Pryor

David Pryor  Mark Pryor

Mark Pryor  Joe T. Robinson and Hattie Caraway

Joe T. Robinson and Hattie Caraway  Joseph Taylor Robinson House

Joseph Taylor Robinson House  Betty Sorensen

Betty Sorensen  State Democratic Convention

State Democratic Convention

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.