calsfoundation@cals.org

Office of Removal and Subsistence

The United States government opened the federal Office of Removal and Subsistence for territory west of the Mississippi River in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1831. The office oversaw removal and subsistence operations relating to the Native American tribes being expelled from their eastern homes, along with providing subsistence for one year after their relocation to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). During the nine years the office was in operation, almost $4.5 million passed through the hands of the officers charged with the operations of the office.

The Choctaw were the first of the five Southeastern tribes to sign a removal treaty. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed by the Choctaw on September 27, 1830, and ratified by the U.S. Congress on February 24, 1831. The February 23, 1831, issue of the Arkansas Gazette printed an alert to the citizens of Arkansas, “To the Farmers, Graziers, and Salt Manufacturers of Arkansas,” urging people not to plant cotton but instead to plant corn and grow the other things that the Indians would require: “The subsistence of such a number of Indians will give profitable employment to our farmers…and at prices that will afford them a better reward for their labor. They [the removal parties] must necessarily scatter large sums of money through our Territory.”

As soon as the treaty was ratified, Captain John B. Clark was named Superintendent of Removal and Subsistence West and ordered to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to repair the old fort and prepare to store items needed for the Indians who were being removed. On May 17, 1831, Clark was ordered to change the location of the office to Little Rock. This office was to be responsible for removal operations, for paying tribal annuities, and for seeing that provisions of the treaties were complied with, such as the delivery of blankets, hoes, blacksmith supplies, and more. Additional responsibilities included having blacksmith shops and mills built in Indian Territory and having repairs made to roads and bridges on the Arkansas routes along which the Indians were expected to travel.

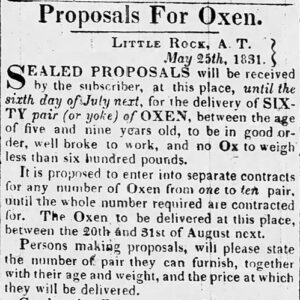

Clark, in preparation for Indian Removal, purchased horses and oxen and made arrangements to have local farmers care for the animals until they were needed. He employed a Little Rock merchant to hire teamsters and act as wagon master. He advertised extensively in the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Advocate newspapers for items needed for removal and subsistence. He contracted for food rations consisting of beef or pork, corn, and salt for the Indians, as well as fodder for the horses and oxen. He rented an office and a warehouse in Little Rock to conduct the business of the office.

By August 2, 1831, Clark was becoming frustrated. He could not find out when the Choctaw were to start, how many were coming, or where they were going to cross the Mississippi River. He wrote, “I will be agreeably surprised if the removal during the approaching fall should pass off only tolerably well.” Clark asked to be relieved by “a person every way better qualified to superintend a matter of so much responsibility.” On October 19, 1831, the Gazette announced that Clark’s replacement, Captain Jacob Brown, had arrived in Little Rock to assume the dual duties of Superintendent of Removal and Subsistence West and Chief Disbursement Officer for Indian Removal.

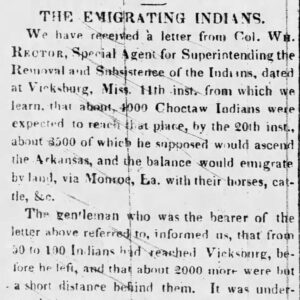

On November 23, 1831, the Arkansas Gazette began a series of announcements regarding “the Emigrating Indians.” On December 18, 1831, a party of eighteen Choctaw with 100 horses arrived on the north side of the Arkansas River opposite Little Rock. This group was soon followed by 594 Choctaw men, women, and children, some with slaves and/or horses. Groups of Choctaw continued to be removed from Mississippi across Arkansas to Indian Territory into the late 1830s.

Between 1831 and 1839, emigrating tribal groups of Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Cherokee—some with slaves, horses, and wagons—removed through Arkansas and were supplied from the office. In addition to overseeing the five Southeastern tribes, the officers were put in charge of two tribal groups of Seneca and Shawnee removed from Ohio to the northeast corner of Indian Territory, as well as the Osage tribe. The second removal of the Quapaw from Arkansas in 1834 to northeast Indian Territory came under the superintendence of the Little Rock office.

Keeping a supply of cash money on hand was a major problem. There were no banks in Arkansas, and the officers or their clerks had to make frequent trips to New Orleans, Louisiana, for money. At times, the United States Department of War was slow in making money available for operations, and the officers in charge frequently complained about the shortage of money. Getting the cash by wagon from Little Rock to Indian Territory to pay annuities or other expenses required accompaniment by guards.

Steamboat traffic at the Little Rock landing near the office picked up dramatically. During a two-month period in 1836, twenty-seven steamboats carrying goods for the removing and removed Indians stopped at the Little Rock landing. Some tribal parties also traveled by steamboats.

Late in 1836, Brown requested to be relieved of duty, and Captain Richard D’Cantillon Collins arrived in March 1837 to assume the responsibility of the office. During the seven-month transitional period, both men worked in the office. In October 1837, Brown completely turned over all responsibilities to Collins and left for other duties.

By the summer of 1839, the bulk of Indian Removal was complete. The responsibilities of the office were transferred to the Southwest Superintendency in Indian Territory, and the Little Rock office closed. By this time, serious problems were coming to light in Collins’s accounts. Collins had stopped sending his quarterly accounting reports to the United States auditor in Washington DC in 1838, but the Department of the Treasury continued to send him funds. In the fall of 1839, Collins found he was being investigated. He became despondent and began drinking alcohol heavily. He was discharged from the Army on February 24, 1841, and died on July 1, 1841, with his accounts still unsettled. At the final accounting of Collins’s operations of the Little Rock office, he was $270,000 in arrears. The money was never recovered, but Collins was rumored to have given money from government funds to men in Little Rock, which they used to build homes. The owners were reported as saying that they owed Collins nothing.

For additional information:

“Died.” Arkansas Gazette, July 7, 1841, p. 3.

“The Emigrating Indians,” Arkansas Gazette, November 23, 1831, p. 3.

“The Emigrating Indians,” Arkansas Gazette, December 28, 1831, p. 3.

Foreman, Grant. Forward to Michael D. Green, A Traveler in Indian Territory, the Journal of Ethan Allen Hitchcock. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

“Highly Interesting.” Arkansas Gazette, February 23, 1831, p. 3.

“The Late Captain Collins’ Account.” Arkansas Gazette, May 25, 1842, p. 2.

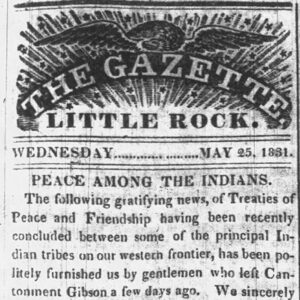

“Peace among the Indians.” Arkansas Gazette, May 25, 1831, p. 3.

Record Group 217, Entry 525, Records of the Department of the Treasury, Indian Affairs, Settled Accounts and Claims. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

Carolyn Yancey Kent

Jacksonville, Arkansas

Arkansas Times and Advocate

Arkansas Times and Advocate Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Native American Emigration Story

Native American Emigration Story  Native American Supplies Ad

Native American Supplies Ad  Native American Treaty Story

Native American Treaty Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.