calsfoundation@cals.org

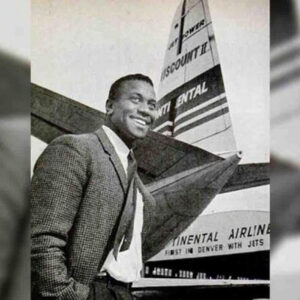

Marlon DeWitt Green (1929–2009)

In 1963, Marlon DeWitt Green, an Arkansas-born African American and former U.S. Air Force pilot, broke the airline industry color barrier when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Continental Airlines had to comply with the State of Colorado’s anti-discrimination laws—there being no conflict with any federal statute—and required that the company hire him. He has been described as the “Jackie Robinson of the airline industry” for overcoming discrimination to become the first black pilot hired by a regularly scheduled commercial passenger airline.

Marlon D. Green was born on June 6, 1929, in El Dorado (Union County) to McKinley Green, who was a domestic worker, and Lucy Longmyre Green, a homemaker. He had four siblings. Despite growing up economically disadvantaged, Green was an excellent student and graduated as the valedictorian of Fairview Elementary. He attended Booker T. Washington High School in El Dorado through the eleventh grade and then converted to Catholicism and received a scholarship to Xavier Preparatory High School in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he graduated as co-valedictorian in 1947. He briefly attended Epiphany Apostolic College in Newburgh, New York, with plans to become a priest. At the end of 1947, however, he was dismissed from that institution (allegedly for sexual activity, a charge he denied) and joined the U.S. Air Force on February 5, 1948, with hopes of becoming an aircraft mechanic.

After basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, Green was stationed in Hawaii on June 5, 1948. After being assigned to an all-black unit whose main duty was performing menial work, Green exhibited a desire to fly planes. He was one of very few black airmen accepted into basic pilot training school in San Antonio, Texas, in March 1950. (One of his classmates was Virgil “Gus” Grissom, who would become one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts.)

Green passed the course and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Over the course of nine years in the U.S. Air Force, he flew a variety of multi-engine aircraft, including bombers, mid-air refueling tankers, and amphibious rescue planes, and served at various air bases.

On December 29, 1951, Green married Eleanor Gallagher, a white Xavier University instructor of physical education whom he had met while in New Orleans. They had six children. They were divorced in 1970. Green later remarried three times, having another son with his second wife, Delores.

In early 1957, Green, then a captain stationed in Japan, resigned his commission to pursue his goal of becoming a commercial airline pilot and earning more money to support his and Eleanor’s growing family. However, the airlines had never employed black pilots before, and Green, who had relocated to Lansing, Michigan, was continually denied employment due to his race. He briefly worked as a pilot for the Michigan State Highway Department but resigned over a dispute about the safety of the plane he was required to use. For several years afterward, he was either unemployed or worked at low-paying menial jobs while continuing to apply for pilot positions.

In June 1957, Continental Airlines, based in Denver, Colorado, invited him to take a flight test, unaware of his race because he had not included a photo of himself with his application. He passed, but five other white, ex–Air Force applicants, all of whom had far less experience than he had, were hired while Green was not. Believing himself to be the victim of racial discrimination, he filed a complaint with the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission (CADC). The CADC agreed and ruled that Continental had to admit Green to a training class. The airline refused and took the matter to the Denver District Court.

In 1959, Continental’s lawyers argued that, as an interstate carrier, the airline was not subject to a state commission’s ruling. On June 11, the court returned the complaint to the commission for revision and set a new court date. Subsequently the complaint was dismissed by the court on June 26. At this point, Green hired a Denver lawyer who appealed the case to the Colorado Supreme Court in 1960; this court sent the case back to the Denver District Court. Green’s lawyer then petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case and was granted a hearing. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy as well as other influential figures and organizations filed “friend of the court” briefs on Green’s behalf.

In April 1963, the Supreme Court, under Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled unanimously in Green’s favor and ordered Continental to admit him to a training course. After more than a year of working out contract terms, Green started with Continental in January 1965. He flew for almost fourteen years, all of them for Continental, before retiring in 1978. As a result of his breaking the airline “color barrier,” he opened the doors for hundreds of other minority pilots, and the Organization of Black Airline Pilots was formed as a result of his victory.

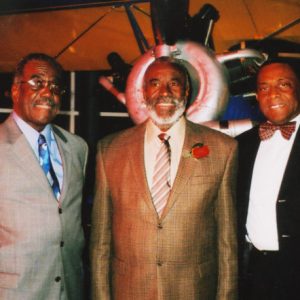

Green received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Organization of Black Airline Pilots in 2003 and was inducted into the Arkansas Aviation Historical Society Hall of Fame in 2005. Continental Airlines named a Boeing 737 the “Capt. Marlon Green” in his honor in 2010. He was also included in the permanent “Black Wings” exhibit at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC.

Green died on July 6, 2009, in Denver. He donated his body to science.

For additional information:

Buggs, Shannon. “Milestone in Diversity.” Houston Chronicle, February 19, 2010. Online at http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/business/6859688.html (accessed January 31, 2024).

Culver, Virginia. “Pilot Marlon D. Green Fought Racial Discrimination.” Denver Post, July 10, 2009. Online at http://www.denverpost.com/obituaries/ci_12805244 (accessed January 31, 2024).

Whitlock, Flint. Turbulence before Takeoff: The Life and Times of Aviation Pioneer Marlon DeWitt Green. Brule, WI: Cable Publishing, 2009.

Flint Whitlock

Denver, Colorado

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Marlon D. Green

Marlon D. Green  Marlon Green

Marlon Green

This country has to be thankful for men like Marlon Green who persevered through undue hardship because of the color of their skin and achieved great things. My heartfelt thanks to you, Sir, for your contribution to our country.