calsfoundation@cals.org

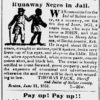

Post-bellum Black Codes

aka: Black Codes

Immediately after the Civil War, Southern states passed onerous laws to maintain their legal control and economic power over African Americans in response to the 1865 passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which ended slavery. Under slavery, whites had disciplined blacks mostly outside the law. After emancipation, fearing blacks’ revenge, slave owners sought to institute a comparable level of legal control over former slaves. While some Black Codes were not harsh, most were: African Americans could not serve on juries; could not sue or testify against whites; were prohibited from owning farms; and were forced to sign unequal labor contracts. The U.S. Congress immediately responded to the Black Codes by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, banning discrimination that treated African Americans as legally and economically inferior, and then the 1868 Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed “equal protection of the laws.” This was followed by a new set of Southern-state laws allowing local officials to discriminate informally. This jousting over black civil rights between the federal government and many Southern states continued through the 1950s.

Arkansas did not pass laws with the severe restrictions like the onerous Black Codes of other “Deep South” states. Blacks could make contracts and own real or personal property, and there was no vagrant law. However, Arkansas did pass laws that prohibited African Americans from attending school with whites and voting, as well as laws with employment restrictions and other legal rights that are often classified as Black Codes.

Arkansas’s comparative mildness was perhaps due to the fact that the political power of a minority of large landowners had pushed the state into secession, but it evaporated in the post-bellum period. As evidence, in 1864, in an election conceded to be “very irregular,” a pro-Union group in Arkansas of ten percent of eligible voters petitioned and were granted presidential recognition of their government. This legislature promptly ratified the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, but did little else for African Americans. Despite this, groups like the Ku Klux Klan often used terror in Arkansas to harass freedmen and negate blacks’ legal and economic rights after the Civil War.

One ostensibly “color-blind” Arkansas law that amounted to a Black Code was Act 122 of 1867, titled “An Act to Regulate the Labor System in This State,” with which the legislature required written labor contracts and prohibited a laborer from breaking a contract. This was extremely powerful because the share system, or sharecropping, was dominant. The sharecropping work day was specified as from sunrise to sunset, and contracts stressed that labor was a family system, with wives’ duties specified along with those of children old enough to work. The laborer fell from a renter who paid rent as a share of the crop to being a wage laborer whose “share” on the crop was paid to him by the landlord. Because he did not own or control his crop share, this continued the exploitation of plantation laborers, most of whom were African American. When a Republican-controlled legislature later reversed this, the Arkansas Gazette approvingly editorialized that it had been a “savage law,” and “adverse to the interests of the property holders and white men of the state.”

While Arkansas did not pass laws as nefarious as the onerous Black Codes of the “Deep South” states, African Americans continued to be legally penalized and harassed within the state.

For additional information:

Stockley, Grif. Ruled By Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Whayne, Jeannie, and Willard Gatewood, eds. The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Williams, C. Fred, et al., eds. A Documentary History of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984.

William P. Kladky

College of Notre Dame of Maryland

Jim Crow Laws

Jim Crow Laws Segregation and Desegregation

Segregation and Desegregation Slave Codes

Slave Codes

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.