calsfoundation@cals.org

Black Rock (Lawrence County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36º06’30″N 091º05’50″W |

| Elevation: | 302 feet |

| Area: | 3.29 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 590 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | October 23, 1884 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

761 |

1,400 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,078 |

853 |

751 |

769 |

662 |

554 |

498 |

848 |

736 |

717 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

662 |

590 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The city of Black Rock in Lawrence County is situated on the Black River at the edge of the Ozark Mountains. It reportedly takes its name from black rocks in the area. The city was a boomtown, rising due to the development of railroads and timber interests, and it was later sustained by the pearling industry.

Black Rock consisted of only a few houses and some cleared farmland prior to the 1882 construction of the Kansas City, Fort Scott, and Gulf Railroad through the area. Immediately, the area was transformed into a boomtown as lumber interests moved in to take advantage of the offerings of the Ozark Mountains. General stores were quickly established, and a sawmill was built on the Black River. In 1884, the city incorporated with a recorded population of 277. By 1890, the city had about ten sawmills. The decade of the 1890s saw the creation of numerous industries, many linked to the timber businesses—shingle mills, planing mills, a furniture factory, a handle factory, and a wagon felloe factory. In addition, Black Rock featured a stone quarry and the Southern Queensware Company, the latter of which was established in 1896 to produce porcelain, earthenware, encaustic tiles, and enamel brick. Between 1890 and 1900, the city grew from 761 to 1,400, though some local sources insist that the city’s population hit near the 3,000 mark in 1897. A Republican newspaper began operations in town in 1888, and the Bank of Black Rock opened in 1892.

African Americans lived in an area locals dubbed “Nigger Hill,” near the property of Coffey Lumber Company. The black part of town had its own school, two churches, and a place for entertainment. However, some local residents did not want black people around, and, on January 12, 1894, a group of unknown vigilantes posted a notice warning all African Americans to leave town within ten days. At the time, about 300 black workers lived in the city, a third of whom reportedly left in response to this threat. One mill did discharge its black laborers, but most other mills and factories stationed guards to prevent violence, and soon the area settled into an armed quiet. However, “whitecappers” continued operating in and around Black Rock, attacking several African Americans in 1898. In 1900, there remained 297 African Americans in Black Rock township, but that number fell to zero by 1920, and Black Rock was soon an acknowledged “sundown town”—a place where white residents forbade African Americans to live.

In 1897, area residents began trolling the Black River after Dr. J. H. Myers found a fourteen-grain, pink ball pearl inside a local mussel. As the pearl rush took hold, most people simply threw away the mussel shells they opened, but Myers shipped a load of the ostensibly worthless shells to Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1899 to be used in the manufacture of buttons. Subsequently, he, along with partners N. R. Townsend and H. W. Townsend established the Black Rock Pearl Button Company, which was reportedly the first button factory in the South. It was later purchased by a company in Davenport, Iowa, and expanded. The Chalmers Button Factory opened around 1909.

By 1908, three newspapers were published in the area. The Powhatan Zinc and Mining Company operated some mines in the area in the early twentieth century. A fire in 1912 destroyed a part of town known as “Rat Row.” In 1919, the First National Bank of Black Rock opened, though it moved to Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) in 1933.

After World War II, however, with the increased availability of plastic buttons, the industry foundered. The last button factory in Black Rock closed in 1954, though mussels are still harvested from the Black River and shipped to China, where they are used for cultured pearls. The main employers in the the city are quarry related. In 1954, the Ben M. Hogan Company opened a rock crusher in Black Rock; this later became the St. Francis Material Company. Sand, gravel, and limestone are also mined in the area. Black Rock schools are a part of the Lawrence County School District. In May 2015, a new bridge spanning the Black River was opened at Black Rock, replacing the 1949 structure, which had been declared deficient by highway officials in 2010.

Betty Clark Dickey, who served as a chief justice and a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court, was born in Black Rock in 1940.

For additional information:

“History of Black Rock.” Lawrence County Historical Quarterly 2 (Fall 1979): 6–11.

Lawrence County, Arkansas: 1815–2001. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2001.

Perkins, Blake. “Race Relations in Western Lawrence County, Arkansas.” Big Muddy: A Journal of the Mississippi River Valley 9.1 (2009): 7–21. Online at http://www.semopress.com/race-relations-in-western-lawrence-county-arkansas/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Black Rock

Black Rock  Black Rock Quarry

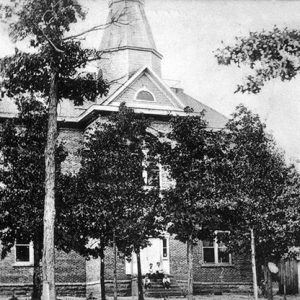

Black Rock Quarry  Black Rock School

Black Rock School  Black Rock Sign

Black Rock Sign  Black Rock Street Scene

Black Rock Street Scene  Lawrence County Map

Lawrence County Map

My father, Howard H. Smith, grew up on the Black River. He lived on the river in a small houseboat, with his father John, his mother Carrie, his sister until she passed at the ripe old age of 16, and his little brother Henry who passed at the age of 7. Not sure when he lost his father, but it had to be prior to 1930 I figure, because my father went to work in the CCC with his mother, also hired on as a cook. His father made a living dragging the bottom of the Black River for mussel shells to sell to the button factory that was in the woods just below the town; they also sold fish. My father used to tell stories of his father’s possibly working for the Pony Express before he got into some kind of trouble in Pennsylvania. He then relocated to Arkansas and made a living the best he could. He also practiced medicine my father recalled. My father always believed the middle name (Vananda) was their true last name since his father signed his name John V. He only used the name Smith during introductions. Wish I had more history on the button factory and Black Rock during that era. His best friends were Wes and Onionhead Woodson, and Charlie.