calsfoundation@cals.org

Elaine (Phillips County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º18’30″N 090º51’07″W |

| Elevation: | 171 feet |

| Area: | 0.51 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 509 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | April 23, 1919 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

377 |

511 |

634 |

744 |

898 |

1,210 |

991 |

846 |

865 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

636 |

509 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The name of Elaine (Phillips County) will always be linked with a race massacre that broke out in the fall of 1919, leaving scores of African Americans dead. Aside from this one memorable incident, the city is representative of life in the Delta region that includes eastern Arkansas.

When Arkansas became a state in 1836, the area of present-day Elaine was still swampland. It was designated as such by the Swamp and Overflow Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1850. Silas Craig and John Martin purchased Phillips County land from the State of Arkansas under the provisions of that act, and the land passed through several owners—including the State of Arkansas a second time, due to unpaid taxes—but was only slightly developed by its various owners.

Around 1892, state geologist John Casper Branner predicted to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) investor Harry Kelley that the swampland of Phillips County would become the richest part of the state. This prediction noted that silt from river flooding created fertile farmland throughout the area. Branner said that three things were needed to develop the land: effective flood control through the building of levees, railroad transportation, and clearing of the timber. Beginning in 1892, Kelley purchased land in the promising area. Eventually, he came to own—alone or through partners—about 35,000 acres. Kelley granted railway right-of-way to the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad, provided that it established a depot at the spot of his choosing. The Iron Mountain was acquired by the Missouri Pacific Railroad before the line and depot were completed, but the promise of a depot was kept in 1906. At first the depot was to be named Kelley, but the same name had already been given to another depot on the line. The name Elaine was chosen—Elaine was the first name of one of Kelley’s daughters, but one of Kelley’s partners later said that the depot was actually named for a popular actress.

Meanwhile, Kelley had sold the oak and ash timber on the land to a St. Louis, Missouri, company. The timber was cut and shipped by John D. Crow and J. M. Countiss, both of whom built houses on the land. In 1911, Kelley and his partners laid the lots of the new city, deliberately creating separate neighborhoods for white and black families. Within a few years, the growing settlement could boast of paved streets, concrete sidewalks, electric lights, brick store buildings, a brick school house, and a well 1,600 feet deep that provided water to all parts of the city. Plantations were established as timber was cleared, while the Howe Lumber Company and the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company remained major employers. The New Madrid Hoop Company and the Acme Cooperage Company also hired many workers. The city was incorporated in 1919, and its first bank was established soon thereafter. Baptist and Methodist churches were built around the same time.

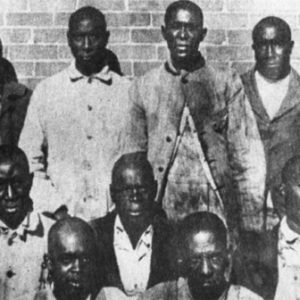

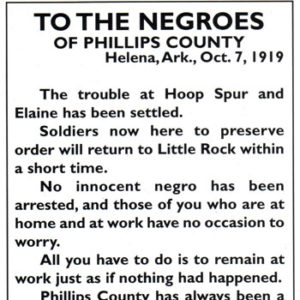

In 1919, the Progressive Farmers and Household Union was holding meetings in Phillips County, promising to help tenant farmers negotiate for better cotton prices. A shooting at a meeting in a church in Hoop Spur, three miles north of Elaine, left one white law enforcement officer dead and another injured. In response, many white residents took up weapons, believing false rumors that the black workers were preparing a violent uprising against white landowners. This rumor spread quickly, and hundreds of people from neighboring counties in Arkansas and Mississippi joined the disorganized vigilante mob. Governor Charles Hillman Brough also specifically requested 500 soldiers to be sent from Camp Pike in North Little Rock (Pulaski County).

A large though undetermined number of black citizens (estimates range into the hundreds) were murdered during the conflict, and many more were detained and imprisoned. Ultimately, seventy-seven black citizens (and no whites) were tried and sentenced for their alleged role in the riot. Twelve who were sentenced to death received legal assistance and eventually were released from prison.

Following this violence, many members of the black population left the area, a large number of them seeking work in northern cities. The city of Elaine, however, continued to grow in spite of this stain on its reputation, and in spite of continued danger of flooding. The Flood of 1927 was one of many that damaged the city; that historic flood resulted in the closing of the Bank of Elaine. The city remained without a bank until the Delta State Bank opened in Elaine in 1948. A tornado damaged the black neighborhood in Elaine in 1930, killing many people and destroying property. (A tornado touched down near Elaine in 2011 but was not as destructive as the 1930 tornado.) In general, the Great Depression created significant hardship for both agriculture and the timber industry in and around Elaine.

Like many other school districts in Arkansas, schools in Elaine experimented with an “open choice” policy that continued de facto segregation in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Eventually, court orders led to more equal desegregation of schools, and other businesses followed the trend of desegregation.

Like other communities in the Arkansas Delta, Elaine experienced depopulation in the last decades of the twentieth century. In 2006, the Elaine school system was consolidated with the Marvell (Phillips County) schools. In February 2017, the Elaine Legacy Center opened in the town; its mission is to memorialize the victims of the Elaine Massacre and the local struggle for civil rights. The Lee Street Community Center also serves as a local cultural anchor.

The centennial of the Elaine Massacre in 2019 drew significant national attention to Elaine, but this attention has not manifested in increased resources for the community, which continues to struggle with a lack of infrastructure, including healthcare services and clean drinking water. A picture of the rusted Elaine water tower was featured in a 2021 USA Today exposé on water contamination in rural communities, and residents have long complained about the smell and taste of local tap water.

Elaine is the hometown of musician Levon Helm. Nationally known newspaper editor Gene Foreman grew up in rural Phillips County and graduated from high school in Elaine. The city is home to a Dairy King restaurant and Hudson’s Fish Market, as well as six churches—three Baptist, two Churches of God, and a church called Casa de Dios (Spanish for “House of God”). The local Lee Grocery Store is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

For additional information:

Allen, E. M. “The Story of Elaine, Arkansas.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 34 (Fall 1996): 30–32.

Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. https://www.elainemuseum.org/ (accessed May 24, 2023).

Gray, Katti. “More than Memorials in Elaine.” Arkansas Times, August 2019, pp. 34–37. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2019/08/04/more-than-memorials-in-elaine (accessed May 24, 2023).

Jones, Mary L. Demoret. “Elaine, Arkansas.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 34 (Fall 1996): 33–37.

Kyte, Willie Mae Countiss. “Elaine, Arkansas.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 23 (December 1984/March 1985): 38–67.

Pascal, Olivia. “Elaine Massacre Descendants Call for Backing up Repentance with Resources.” Facing South, October 8, 2021. https://www.facingsouth.org/2021/10/elaine-massacre-descendants-call-backing-repentance-resources (accessed May 24, 2023).

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Stopford, Annie. Trauma and Repair: Confronting Segregation and Violence in America. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2020.

Steven Teske

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Cypress Logging

Cypress Logging  Elaine Street Scene

Elaine Street Scene  Elaine Massacre Defendants

Elaine Massacre Defendants  Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article

Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article  Elaine Massacre Flyer

Elaine Massacre Flyer  Elaine Methodist Church

Elaine Methodist Church  Elaine Street Scene

Elaine Street Scene  Lee Grocery Store

Lee Grocery Store  Phillips County Map

Phillips County Map

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.