calsfoundation@cals.org

Fargo (Monroe County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34°57’05″N 091°10’48″W |

| Elevation: | 200 feet |

| Area: | 0.46 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 57 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 6, 1987 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

140 |

118 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

98 |

57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fargo is a town on U.S. Highway 49 in northern Monroe County, north of Interstate 40. Fargo came into existence due to the railroad industry and later was home to a significant school for African Americans.

Various Native American artifacts have been found in Monroe County, indicating that it has been inhabited at least sporadically for centuries. European hunters and trappers had arrived by the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the county itself was established in 1829, several years before Arkansas became a state. The northern part of the county, drained by the Cache River, was largely uninhabited throughout the nineteenth century.

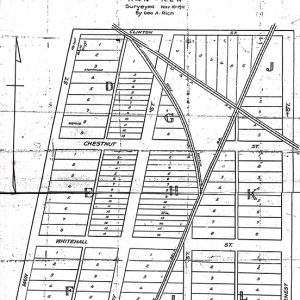

The St. Louis Southwestern Railway, known as the Cotton Belt, was constructed across Arkansas from Texarkana (Miller County) to St. Francis (Clay County) between 1881 and 1883. The railroad crossed northern Monroe County, but a depot was not established at the location of Fargo until the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA) was built to connect Seligman, Missouri, to Helena (Phillips County). The two railroads crossed at the location of Fargo, and a post office of that name was established in 1898, although a jointly owned depot was not built until 1911. According to a local history, the name was suggested by a conductor on the Cotton Belt Railroad. The town was platted in 1911 on land owned by Leroy Washington Mahon, an African-American man who had migrated to Arkansas from South Carolina and started a farm in the area that became Fargo.

Floyd Brown, a recent graduate of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, visited Brinkley (Monroe County) in 1915. He decided to relocate to Arkansas and found a school to be operated similar to Tuskegee. He returned in 1919 with $2.85, and he acquired land in Fargo and began operating the Fargo Agricultural School. For the next thirty years, Brown—along with his wife, Lillie Epps Brown, and a small staff of teachers—taught African-American students English, music, history, mathematics, and science, along with vocational skills including carpentry, plumbing, farming, childcare, sewing, food preparation, and family income management. Unlike similar schools in Arkansas, the Fargo Agricultural School was privately owned and not supported by any religious organization.

Flooding in the spring of 1945 destroyed the M&NA track between Fargo and Kensett (White County). Financial struggles of the railroad, combined with the scarcity of materials due to World War II, delayed repair of the railroad. By 1947, the railroad was in receivership for the third time in its history, and the line from Fargo to Helena was acquired by the Helena and Northwestern Railroad in 1949. When that railroad went out of business, the track from Fargo to Cotton Plant (Woodruff County), about six miles, became the Cotton Plant-Fargo Railway in January 1952. Serving the Southwest Veneer Company and other Cotton Plant businesses, the line operated until the 1970s and was the last portion of the M&NA in use.

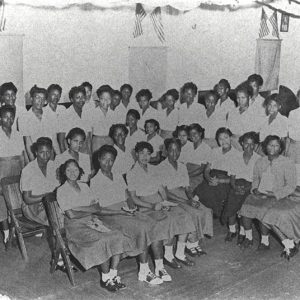

Meanwhile, Brown sold the Fargo Agricultural School to the State of Arkansas in 1949 and moved to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). The state changed the school into the Fargo Negro Girls Training School. The school’s buildings were demolished and replaced starting in 1955. In 1960, the Floyd Brown-Fargo Agricultural Museum opened on school property, thanks to a donation from the Browns. Graduates of the school gather regularly for reunions at the museum.

Similar training schools were operated by the State of Arkansas in Alexander (Pulaski and Saline counties), Wrightsville (Pulaski County), and Pine Bluff. Because of desegregation, the system was adjusted in 1968, and the students in Fargo were transferred to the facility in Alexander. With the closing of the school in Fargo, as well as the end of the railroad, the population declined, and the post office closed in 1976. The Arkansas Land and Farm Development Corporation took over the school property in 1981 to provide financial assistance to rural African-American families in Monroe County.

In 1987, the remaining citizens of Fargo voted to incorporate as a town to obtain federal and state money for roads and water systems. This did not end the decline in population, which fell from 140 in 1990 to ninety-eight in 2010. Of those ninety-eight citizens, forty-three were white and fifty-five were African American. The Fargo Training School Historic District, consisting of the buildings constructed between 1955 and 1960 as well as an older gymnasium, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 2010.

For additional information:

Fair, James R., Jr. The North Arkansas Line. Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books, 1969.

“Fargo Training School Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.org/National-Register-Listings/PDF/MO0163.nr.pdf (accessed October 13, 2020).

Handley, Lawrence R. “Settlement across Northern Arkansas as Influenced by the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Winter 1974): 273–292.

Steven Teske

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

ALFDC Business Center

ALFDC Business Center  Floyd Brown

Floyd Brown  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Fargo Community Center

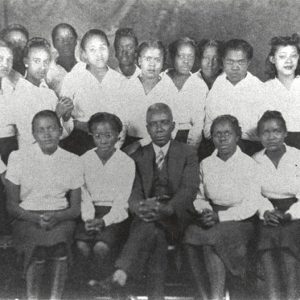

Fargo Community Center  Fargo Girls Chorus

Fargo Girls Chorus  Fargo Plat

Fargo Plat  Fargo School Girls

Fargo School Girls  Fargo Street Scene

Fargo Street Scene  Fargo Street Scene

Fargo Street Scene  Monroe County Map

Monroe County Map

On “Finding Your Roots” Dr. Louis Gates shared that Fargo, Arkansas, was built in 1911 on 40 acres of land donated by Leroy Mohan, an African American who had been enslaved in South Carolina. Changing his name from Leroy Stenhous, he found his way to Arkansas. Leroy Mohan is an ancestor of Sasheer Zamata. Please see Season 6 Episode 3.

I too viewed the “Finding Your Roots” episode where Dr. Gates and his research team unveiled the discovery of Fargo, Arkansas, having been originally purchased as 40 acres of land then platted and sold to other African Americans to build homes by a former slave from South Carolina renamed Leroy Washington Mahon Stenhouse. My family’s paternal tree is Washington and we have only been able to trace back one generation. We look forward to more detailed information regarding Mr. Leroy Washington and names of those who originally purchased the land that formed Fargo so that we may be able to obtain any information that helps with our family tree search.