calsfoundation@cals.org

Harvey Crowley Couch (1877–1941)

Influenced by a teacher’s counsel, Harvey Crowley Couch helped bring Arkansas from an agricultural economy in the early twentieth century to more of a balance between agriculture and industry. His persuasiveness with investors from New York and his ingenuity, initiative, and energy had a positive effect on Arkansas’s national reputation among businessmen. He ultimately owned several railroad lines and a telephone company and was responsible for what became the state’s largest utility, Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L).

Harvey Couch was born on August 21, 1877, in Calhoun (Columbia County) to Tom Couch, a farmer turned minister, and Mamie Heard Couch. He had five siblings. Couch attended school in Calhoun two months out of each year, as did many farmers’ children then. When he was seventeen, the family moved to Magnolia (Columbia County) because his father was no longer physically able to farm. There, he attended his first nine-month school term as a six-foot, bulky classmate of twelve- and thirteen-year-olds. When he became withdrawn and considered dropping out, his teacher, Pat Neff, challenged him with adages that founded Couch’s lifelong ambition: “A winner never quits” and “Men like you have built empires.” Pat Neff eventually became the governor of Texas and president of Baylor University. Two years later, however, Couch left school to help support his siblings.

Couch’s first job off the family’s farm was to fire the boiler of a local cotton gin’s steam engine and bring it up to the required pressure. He earned fifty cents a day. While waiting to hear about his application to the Railway Mail Service (SLR), he became a drugstore clerk. His hard work and honesty prompted his boss to assign him the additional task of collecting overdue accounts.

At age twenty-one, he was hired as a mail clerk on the St. Louis–Texarkana route of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway and was soon transferred to head clerk on the St. Louis Southwestern Railway. At a water stop, Couch noticed a construction crew raising a pole—not for the telegraph line but as part of a long-distance telephone system. After questioning the linemen, he saw a chance to help bring phone service to places like Magnolia. He paid a colleague fifty dollars to exchange routes so he could clerk the Magnolia–north Louisiana route. Enlisting his brother Pete as crew leader to move and set up poles and a postmaster in Louisiana to become a partner, Couch began the North Louisiana Telephone Company (NLTC). The line expanded, and Couch bought his partner’s share of the business.

Couch’s expanding telephone system took him to Athens, Louisiana, where he met Jessie Johnson. They married on October 4, 1904. The couple had five children.

In 1911, Couch sold NLTC, which then had 1,500 miles of line and fifty exchanges in four states, to Southwestern Bell for over a million dollars. Too young to retire, he determined to build another company. In 1914, at the age of thirty-five, he bought from Jack Wilson the only electric transmission line in the state, which ran twenty-two miles between Malvern (Hot Spring County) and Arkadelphia (Clark County). The system ran only at night. Sixteen years later, bolstered by hydroelectric dams on the Ouachita River, the company that Couch named Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L) had 3,000 miles of line serving cities and towns in sixty-three of the state’s seventy-five counties as well as 3,000 farmers. The company, now called Entergy, currently serves 2.4 million customers in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. In 1922, Couch started WOK, the first radio station in Arkansas, at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

Harvey Couch created three interconnected utility companies from scratch—AP&L, Mississippi Power and Light, and Louisiana Power and Light. He also built the first modern natural gas–fired power plant in the lower Mississippi River Valley, near Monroe, Louisiana. With permits from Washington DC, he built Remmel and Carpenter dams in Garland County, using stones from the riverbanks and timber from the soon-to-be-inundated lands, thereby creating Lake Hamilton and Lake Catherine, the latter named for his daughter. The only luxury the longtime resident of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) (where AP&L also had its headquarters) allowed himself was a rustic log cabin on Lake Catherine, just outside of Hot Springs (Garland County). He called it Couchwood, and there he entertained everyone who had helped him in his rise to fame, as well as international bankers, and presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

During the Flood of 1927, Governor John E. Martineau appointed Couch flood relief director and supervisor of the Red Cross rescue operations. After the drought of 1930, Couch was appointed state relief chairman. In this position, he was able to help Arkansas senator Joe T. Robinson obtain $20 million in federal loans to Arkansas farmers.

Hoover also appointed Couch to the seven-member board for the president’s newly formed emergency Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), which operated from 1931 to 1956. The RFC was the president’s way of getting the government involved. The new program’s mission was to strengthen confidence, facilitate exports, protect and aid agriculture, make temporary advances to industries, and stimulate employment. Couch was one of seven directors of the RFC, and he moved to Washington DC for three years. He served as supervisor of the public works section, overseeing budgets and encouraging the building of water and sewage systems, bridges, and electric lines. He and Jesse Jones were the only Hoover appointees to stay on after Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected.

After spending his life acquiring money, now Couch simply distributed it, but he kept up his Arkansas connection at Couchwood with wiener roasts (his favorite food was the hotdog) for neighbors and their children.

Still, the RFC was not helping everyone. The Public Works Administration (PWA) was established in 1933 under Roosevelt to fund large-scale projects-schools, dams, and civic improvements. Couch resigned from RFC, staying on until the PWA ran smoothly. He took 1,400 employees of RFC on a farewell cruise along the Potomac—complete with hot dogs and dance music.

In 1937, Couch acquired stock in the Kansas City Southern Railroad (KCS) and soon assumed control of it. In 1939, he combined it with the Louisiana and Arkansas Railway, which he had purchased in February 1928 (he also added the Louisiana Railroad and Navigational Company the year after). Control of the KCS allowed Couch to form a merger in 1939 that stretched the system from New Orleans to Kansas City. He upgraded the aging system and announced the development of an air-rail-motor transportation system that followed the KCS routes. He received expedited government approval.

Returning to Arkansas in 1934, Couch took on his final two projects. One was devising a new type of electrical distribution system using one insulated wire and a grounded neutral, which was easier to get to farms. This cut the cost from $1,500 per mile to $750. Instead of patenting the system, he turned it over to the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the first connections included Magnet Cove (Hot Spring County) and Prattsville (Grant County) and garnered nation-wide publicity.

Couch’s second project was practical for the future. He thought that, instead of being only a provider of resources—water, cotton, rice, timber, etc.—the state could process resources as well. This would mean manufacturing industries, with pricing and payments staying in Arkansas. He thus worked to develop the state’s economy by building industries to process lumber, cotton, glass, and bauxite into useable products.

Couch died at Couchwood on July 30, 1941, of heart disease. After funeral services in Pine Bluff, a special train transported his body to Magnolia, where he was buried beside his father and mother.

For additional information:

Couch-Remmel Family Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Olson, James S. “Harvey C. Couch and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Autumn 1973): 217–225.

Tatman, Donald Angus. Sparks of Genius That Helped Build Arkansas. Pine Bluff, AR: Delta Press, 1997.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Wilson, Stephen. Harvey Couch: An Entrepreneur Brings Electricity to Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

Wilson, Winston P. Harvey Couch: The Master Builder. Nashville, TN: Broadman Press, 1947.

Patricia Paulus Laster

Benton, Arkansas

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

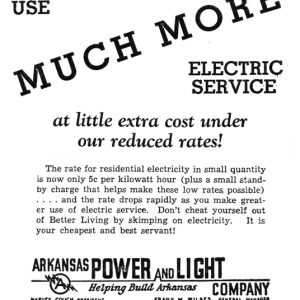

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad

Arkansas Power & Light (AP&L) Ad  Couch in Washington

Couch in Washington  Couch Power Plant in Stamps

Couch Power Plant in Stamps  Harvey Couch with Will Rogers

Harvey Couch with Will Rogers  Harvey Couch

Harvey Couch  Couchwood Historic District

Couchwood Historic District

(Editors note: The Bylander narratives are oral history narratives submitted by Jerry Bylander on behalf of his uncles Ernest Eugene Bylander and Edgar Gearhart Bylander and other members of the Bylander family.) Harvey Couch, president of Arkansas Power and Light, had a home on large acreage on Lake Catherine, near Hot Springs. He had deer and several wild animals, but he wanted a pair of buffalo. He bought three buffalo in Oklahoma. He gave some of these animals to the zoo, and they got the Arkansas State Highway Dept. to send a truck for them. The zoo kept the buffalo in a pen with a goat. Mr. Adams (whom the Little Rock Airport is named for) owned a wholesale produce company, and he, along with other wholesale firms, would give us old vegetables and fruit, and I would haul it in the state fairs Model T Ford touring car. I would feed the old peaches to the goat. One time we got a load of peaches that had gotten over-ripe, and we threw them in the buffalo-elk-goat pen for the goats to eat. One of the buffaloes ate some of the spoiled peaches and diedwhen he was cut open for an autopsy, his stomach was full of peach pits. They had the head mounted and gave it to Dad [Ernest G. Bylander]. I dont know where it ended up.