calsfoundation@cals.org

Bonanza Race War of 1904

The Bonanza Race War of 1904 was a race riot/labor war that occurred in the coal-mining city of Bonanza (Sebastian County) and resulted in the expulsion of African Americans from the city following several days of violence. The event is indicative of a general antipathy toward black labor in the coal mines of western Arkansas, and, by the end of the decade, African Americans could reportedly be found in only two mining communities, having been driven from the rest.

Bonanza was a coal-mining city even before its incorporation in 1898. Central Coal and Coke Company operated the only three mines there, and the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) provided easy transportation, both for coal and other goods and for travelers. Due to the mines, Bonanza was the largest city in its township and hosted all the businesses typical of a mining city, including a company store, restaurants, saloons, and general stores.

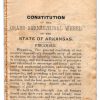

African Americans likely worked in the coal mines of western Arkansas from the beginning, most notably under the convict lease system, whereby the State of Arkansas rented out prisoners to private businesses, including mining companies. At the notorious mines in Coal Hill (Johnson County), black convicts labored under barbaric conditions that included regular beatings. Mining companies also employed black laborers in order to break strikes. For example, in 1899, after representatives of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) launched a strike against the Kansas and Texas Coal Company at Huntington (Sebastian County), the company began filling its mines with labor imported from out of state, consisting primarily of African Americans. In response, the striking miners directed a lot of their violence against their black replacements.

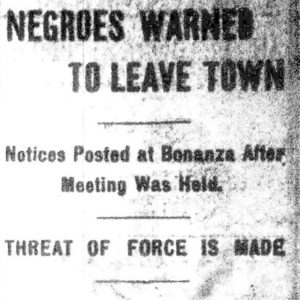

The source material relating to the Bonanza Race War consists largely of articles from the Arkansas Gazette and regional newspapers of the time. The earliest mention of the event comes from the April 30, 1904, issue of the Arkansas Gazette, which reported that approximately 200 white citizens of Bonanza held a meeting on April 27 and passed resolutions “demanding that about forty Negroes employed by Central Coal and Coke Company leave town,” promising to effect such a removal by force if necessary. According to rumor, the union was involved in this attempt at intimidation, leading union local No. 1199 of the UMWA to pass its own resolution two days later, repudiating “as false and unfounded this malicious report.” (Newspaper reports are contradictory as to whether the black mine workers were members of the union, as well as whether the African Americans in question were recent arrivals.) The company publicly pledged its protection for the black laborers, and a tense peace seems to have existed for the next few days.

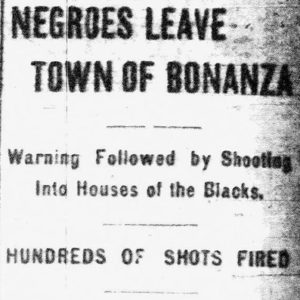

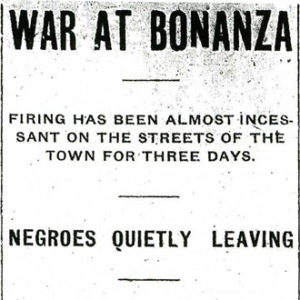

On the night of Saturday, April 30, however, tensions exploded when black and white patrons of Clinton’s Saloon traded shots outside the establishment. This led to a city-wide exchange of bullets; the Fort Smith Times reported that “as many as 500 shots were fired during the night.” Most of these shots were apparently fired into the homes of African Americans. Armed mobs roamed the town, shooting sporadically and warning black residents to leave within twenty-four hours. The gunfire continued through Sunday night, but no one was reported killed or injured. By Monday, May 2, most of the black women and children had already left the city, and other black residents were making arrangements to leave quickly. The Arkansas Gazette reported on May 7 that nearly all African Americans had left the city.

The Bonanza Race War fits in with other examples of racial and labor violence in the state. In 1894, whitecappers tried to drive black workers from the mills and factories of Black Rock (Lawrence County), and, five years later, white residents of Paragould (Greene County) also tried to drive off black workers due to labor concerns. In 1910, Arthur Alvin Steel of the Arkansas Geological Survey reported that African Americans had been driven from all the mining camps save those at Huntington and Russellville (Pope County). The coal mines of Arkansas attracted Italians, Germans, and other European immigrants, who had added motive for committing violence against African Americans—in an era when such immigrants were considered racially suspect and low on the racial hierarchy, attacking African Americans was often a means of attaining “whiteness.” The town of Bonanza was home to European immigrants and had Catholic churches for both Irish and Italian congregations.

The Bonanza Race War illustrates how racial antipathies and conflicts between management and labor were often intertwined. Too, events such as this help explain local demographics; though Fort Smith (Sebastian County) has long hosted a significant African-American population, many rural Sebastian County cities such as Bonanza are all or predominantly white, having been transformed into “sundown towns”—places where African Americans have been forbidden to reside, often through the threat of violence. By 1930, the township in which Bonanza is located recorded no African-American residents, and it was still all white as of the 2000 Census.

For additional information:

Steel, A. A. Coal Mining in Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing Co., 1910.

“War at Bonanza.” Fort Smith Times. May 2, 1904, p. 1.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Labor Movement

Labor Movement African Americans in Bonanza

African Americans in Bonanza  African Americans in Bonanza

African Americans in Bonanza  War at Bonanza

War at Bonanza

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.