calsfoundation@cals.org

Ozark Folklore Society

aka: Arkansas Folklore Society

The Ozark Folklore Society was founded on April 30, 1949, at an informal meeting convened by poet John Gould Fletcher, who was then serving as artist-in-residence at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), and held in the study of folklorist Vance Randolph in Eureka Springs (Carroll County). Fletcher was named president and Randolph vice president. Just over a year later, on May 10, 1950, Fletcher drowned himself in a pond near his house in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Randolph assumed the office of president. In the first issue of its newsletter, Ozark Folklore Society, Randolph stated the mission of the society: “We believe that the Ozark region of Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma has a richer store of traditional culture than any comparable area in the United States. The purpose of the Ozark Folklore Society is to collect such material and deposit it in the archives at the University of Arkansas.”

The founding directors of the society, in addition to Randolph, included Otto Ernest Rayburn, vice president; UA folklore professor Mary Celestia Parler, secretary-treasurer; Merlin P. Mitchell, Parler’s field assistant, who held the office of “researcher”; writer Charlie May Simon, Fletcher’s widow; Robert Morris, a professor of English at UA; and May Kennedy McCord, a writer and well-known popularizer of Ozark folkways. In addition to the stated goals of collecting and preservation, the society held the annual Folk Festival. The festival hosted performances by Ozark singers and instrumental musicians, a presentation by a professional folklorist or writer, and opportunities for fellowship among the members. J. Frank Dobie, the renowned Texas writer and folklorist, spoke at the first festival.

Despite Fletcher’s death, the society grew and maintained its activities for most of the rest of the decade. In 1951, the name was changed to Arkansas Folklore Society, with a corresponding change in the title of its publication. Among the speakers at the annual festivals were Harry Ashmore, executive editor of the Arkansas Gazette, and John Quincy Wolf, noted collector of Ozark folklore and music.

The mimeographed pages of the society’s newsletter contain the names of many well-known collectors, performers, and scholars of Arkansas folklore, including Irene Carlisle, Mary Jo Davis (who performed at the 1951 festival), Doney Hammontree, Booth Campbell, and Fred High. The 1953 issue refers to James C. Morris (better known as Jimmy Driftwood) of Timbo (Stone County) as a “capable and enthusiastic collector.”

In 1954, the society published A Checklist of Arkansas Songs, comprising 557 songs collected by Mitchell, Parler, and Carlisle. A supplement, issued in 1957, included 298 more songs recorded in that interval.

The society went dormant about 1960 despite its membership of nearly 300. It was reorganized in 1978 with Dr. Tate C. “Piney” Page, former professor at Western Kentucky University, as president; David Newbern, an early administrator of the Ozark Folk Center, as vice president; and Robert Cochran, Parler’s successor as folklore professor at UA, as secretary. The announced intention was to provide a framework for folklore research, continuing to use the University of Arkansas Libraries as a clearinghouse and archival repository. Since that time, with the deaths of many of the original members and supporters of the society, work in Ozark and popular culture has been subsumed into the activities of the university’s Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies.

For additional information:

Arkansas Folklore 1–8 (1950–1958). Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Arkansas Folklore 1977–1979. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Cochran, Robert. Vance Randolph: An Ozark Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985.

Mary Celestia Parler Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Otto Ernest Rayburn Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Sutton, Leslie. “Folklore Society Reorganizes.” Northwest Arkansas Times, December 7, 1977, p. 8.

Vance Randolph Collection. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Ethel C. Simpson

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Booth Campbell

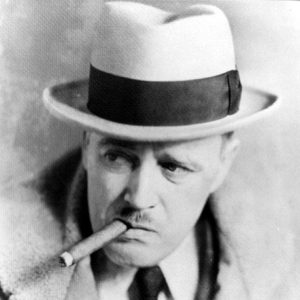

Booth Campbell  John Gould Fletcher

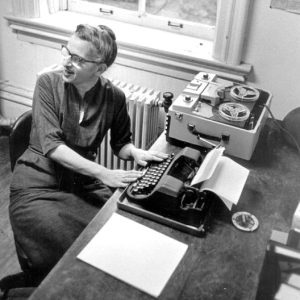

John Gould Fletcher  Mary Parler

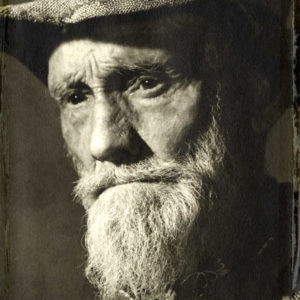

Mary Parler  Vance Randolph

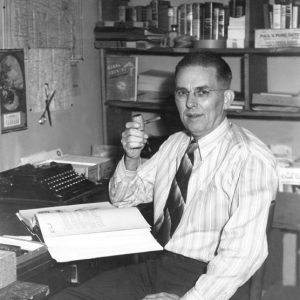

Vance Randolph  Otto Ernest Rayburn

Otto Ernest Rayburn  Charlie May Simon

Charlie May Simon

When I lived in Springfield, Missouri, May Kennedy McCord was my dear friend and neighbor, and many hours were spent at her house at 1111 North Jefferson singing the old songs and talking about the Ozarks. She was one of the reasons I moved to Eureka Springs in 1983. Luckily, I found a few informants I could record who have since passed on. I still perform the old songs whether they be called Ozark folksongs, Appalachian folksongs, Smoky Mt. folksongs, etc. I started collecting the old songs in 1959 and have worked since then to keep these old songs and the spirit of the Ozarks hillbilly alive. I once read that someone said, “How can we know where we’re going if we don’t know where we’ve been?” I only hope the younger generation will see the value in these songs and be keepers of the flame.

Arkansas Red-Ozark Troubadour