calsfoundation@cals.org

Classical Music and Opera

Although Arkansas is generally better known for its blues, gospel, folk, country, and rock and roll performers, classical and opera music have deep roots in Arkansas history and culture, often appearing in interesting ways in unusual places.

Internationally famous Arkansan composers of classical music include Scott Joplin, Florence Beatrice Smith Price, William Grant Still, and Conlon Nancarrow. Sarah Caldwell, who grew up in Fayetteville (Washington County), was a longtime opera director in Boston, Massachusetts, and the first woman to conduct an opera at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. Arkansas has been home to opera singers Mary Lewis, Barbara Hendricks, Susan Dunn, Marjorie Lawrence, Mary McCormic, Robert McFerrin Sr., and William Warfield. Classical music figures prominently in academic music degree programs at the state’s universities, and Arkansans have at various times held regular opera performances at the Opera Theatre at Wildwood Park for the Arts in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and at Opera in the Ozarks at Inspiration Point in Eureka Springs (Carroll County). The Arkansas Symphony Orchestra in Little Rock is one of ten symphony orchestras in the state.

Classical Music: Early Arkansas History

Music figured prominently in early Arkansas history, with traveler Washington Irving identifying French chansons being sung at Arkansas Post in 1832. Early American pioneers brought their own music with them. This folk music was transmitted orally well into the twentieth century and fell into categories such as ballads, religious hymns, and even scatological songs. Familiar tunes usually provided by one or more fiddle players accompanied dancing. Early Arkansans also brought along pianos and sheet music. Surviving sheet music collections contain popular songs as well as non-vocal compositions, including polkas, waltzes, marches, and transcriptions of opera arias. The most “refined” were the parlor songs, while others more suited to the porch than the parlor, such as “Juanita,” were performed outdoors.

Church music fell into denominational camps: those who used organs, pianos, or other instrumental combinations and those who did not and depended on singing schools to teach the “shape note” singing tradition. Training in church music remains an important part of the curriculum at Ouachita Baptist University (OBU) in Arkadelphia (Clark County) and Harding University in Searcy (White County).

The first recorded formal concert in Arkansas was held at Arkansas Post in 1821 by a Mr. Fries. Before the Civil War, Batesville (Independence County) residents put on a performance of Joseph Haydn’s The Creation, which requires an orchestra, chorus, and soloists. After 1853, H. G. Hollenberg’s Great Southwest Music House out of Memphis, Tennessee, was the major source for both sheet music—which Hollenberg started publishing himself—and musical instruments. Hollenberg’s Little Rock branch was long the capital city’s leading supplier. Moses Melody Shop in Little Rock followed later. Violinist Ferdinand Zellner gave an Arkansas-related title to his “Fayetteville Polka” in 1856. Benjamin Franklin Scull, son of a pioneering Arkansas County family, composed music for minstrel troupes while studying medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His “I Am Near to Thee,” with words by Little Rock newspaperman John E. Knight and dedicated to Mary E. Woodruff, was published in 1858.

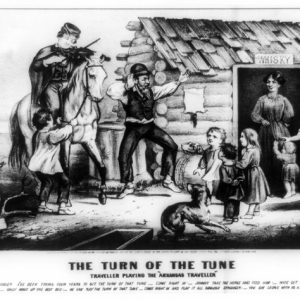

Since Arkansas has for a long time occupied a distinctive position in the American imagination, the tune, story, and visual image of “The Arkansas Traveler” attracted international attention. The Arkansas-based version of the Traveler story is said to have begun in 1840. Sandford C. (Sandy) Faulkner—for whom Faulkner County would later be named—got lost in rural Arkansas and asked for directions at a humble log home. Faulkner, a natural performer, turned the experience into an entertaining presentation in which the Traveler was greeted by the Squatter at the log cabin with humorously evasive responses to his questions. Finally, the Traveler offered to play the second half, or “turn,” of the fiddle tune the Squatter was playing. The tune was the “Arkansas Traveler.” In his happiness at hearing the turn, the Squatter mustered all of the hospitality of his household for the Traveler. When the Traveler again asked directions, the Squatter offered them but suggested that the Traveler would be lucky to make it back to the cottage “whar you kin cum and play on thara’r tune as long as you please.”

Following the publication of the story, both Mose Case—an entertainer from Buffalo, New York—and Cincinnati violinist Jose Tasso produced sheet music versions of the tune (the Case version was published in 1863 and distributed widely), and violinist Henri Vieuxtemps played an elaborate set of variations of it, as well as including it in his American Bouquet (No. 6) series. Twentieth-century composer David W. Guion in 1929 wrote a difficult piano concert transcription based on the tune, and Harl McDonald’s The Legend of the Arkansas Traveler was recorded by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1939. An arrangement was also recorded by the Boston Pops Orchestra. Finally, this fiddle tune, improbably supplied with words by a committee, was legislated into becoming Arkansas’s official state song between 1949 and 1963. It is now the state’s official historical song.

Classical Music: Civil War through the Gilded Age

Many backwoods soldiers received an expanded musical education during the war. The tune “Wait for the Wagon” was fitted with pro-secession and anti-secession lyrics in the spring of 1861, and Harry MacCarthy, “the Arkansas Comedian,” authored the South’s first highly popular song, “The Bonnie Blue Flag.” Civil War brass bands, with their own special music but also transcriptions of newly popular songs, performed on the Fourth of July and other occasions. “Dixie” was rendered by bands during and after the war. The popular song “Lorena” was the only tune one southern Arkansas band knew.

After the war, town bands became popular; Bradford (White County) had an ensemble that included women. Academic institutions, at first academies and then colleges, supplied music education and offered performances. Little Rock’s St. Johns’ College and Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas—UA) in Fayetteville were music centers. UA’s founding director of music in 1872 was Wolf Detleff Carl Botefuhr; Moonlight on the Poteau was one of his many compositions. Botefuhr moved to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in 1881, where he opened his own conservatory and taught the young William Worth Bailey, a talented blind violinist called “the American Paganini.” In 1923, Bailey became the concertmaster of the Fort Smith Symphony; his wife, Katherine Price Bailey, was the conductor and remained in that position for many years.

Opera: Post Civil War through the Gilded Age

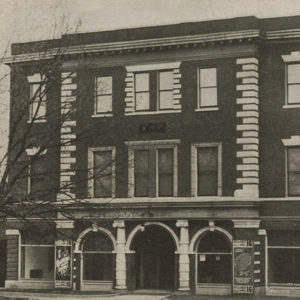

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century saw a rise in the popularity of classical music, especially opera—considered a “higher” form of music by the educated elite. In 1870, Little Rock’s first visiting opera company, headed by the famed tenor Pasquilino Brignoli, came by steamboat and presented six operas in a shabby setting, and Little Rock responded by erecting a $50,000 opera house in 1873. Many other communities, including Fort Smith, Hot Springs (Garland County), Clarendon (Monroe County), Cotton Plant (Woodruff County), Van Buren (Crawford County), and St. Joe (Searcy County) built what were styled “opera houses.” These structures were used as venues for all kinds of local performances and school events as well as for major national companies passing through by train. However, plays and minstrel shows were more common than opera companies.

Classical Music: Twentieth Century

During the early part of the twentieth century, music clubs around the state, as well as individual music supporters, began pushing for music education for the young and for quality musical performances for the enjoyment of the citizenry.

The music club movement was central to organized culture. Little Rock’s Musical Coterie, founded in 1893, was one of the first groups preceding the Arkansas Federation of Music Clubs formed in 1908. By 1940, there were forty senior and thirty junior clubs around the state. Music was not neglected at the state’s colleges; Frederick Harwood worked from 1913 to 1946 building a music program at what is now Henderson State University in Arkadelphia.

For about a decade starting in 1912, Little Rock held May festivals that imported outside orchestras and performers. The Community Concerts organization was active for more than ten years in Little Rock and in other communities in the 1950s. Famous twentieth-century violinist Jascha Heifetz came to El Dorado (Union County) during the oil-boom days. Colleges and high school auditoriums or basketball courts were used for concerts. Radio stations regularly broadcast classical music, including Saturday matinees live from the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

In 1933, the Little Rock Civic Symphony, precursor of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, was organized and directed by Laurence Powell of the music department at Little Rock Junior College (now the University of Arkansas at Little Rock) as part of the school’s music program. Powell had already organized an orchestra in Fayetteville. Low pay led him to leave Little Rock in 1939, and the group folded. The State Symphony Orchestra and the Arkansas Philharmonic Society followed, but the current Arkansas Symphony Orchestra was not established until 1960. By 2013, it was the only symphonic body in the state with some salaried players; all other orchestras operate completely on a per-service basis. Paul W. Klipsch, who began manufacturing high-end high-fidelity speakers in Hope (Hempstead County) in 1946, was an important symphony supporter.

Signs of renewed interest in classical music emerged in the mid-1950s. In 1966, the Arkansas Arts Council, which received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, was created to advance the arts in Arkansas, including classical music. New regional orchestras appeared in the mid-twentieth century. The Jonesboro Symphony Orchestra became successively the Northeast Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and then the Delta Symphony Orchestra. Aided by Arkansas Arts Council grants, these orchestras organized youth concerts, held competitions, and expanded their outreach. By 2013, symphony orchestras could be found in Conway (Faulkner County), Fort Smith, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), El Dorado, Texarkana (Miller County), Fayetteville, Mountain Home (Baxter County), Bentonville (Benton County), and Jonesboro (Craighead County). Children’s concerts, pop concerts, and salutes to the military were featured prominently in regional orchestras.

The Arkansas Symphony was praised by the music critic of the Washington Post for its 1976 Bicentennial concert in the national’s capital, and the Fort Smith Symphony made three recordings of William Grant Still compositions for the Naxos label. These various orchestras were not without problems, however. The North Arkansas Symphony, which had made a commercial recording, had to cancel its last concert in 2008 and shut down. The Symphony of Northwest Arkansas started up two years later. Band music, aside from its connection with high school and college football games, declined in popularity, and only one semi-professional band remained active in the state.

What is now the Diamond State Chorus, a men’s barbershop singing group, started in 1955, with the women’s group, now called Top of the Rock Chorus, starting in 1961. The Arkansas Chamber Singers, founded in 1979, became the premier volunteer chamber chorus in the state.

A musical series, Artspree, succeeded in bringing a variety of individuals and groups to Little Rock, and the Chamber Music Society of Little Rock, founded in 1952, brought in notable ensembles and individuals. In Helena (Phillips County), the Warfield Concerts provided free admission; classical music figured prominently in the offerings. Phillips County’s Lily Peter brought the Philadelphia Orchestra at her own expense to play in Little Rock in 1969. The Hot Springs Music Festival started in 1995 and paired students with professionals to offer public concerts.

Opera: Twentieth Century

Opera did not fare as well as classical music in the twentieth century, although there were some successes. Beginning in 1941, Hot Springs was home to retired opera star and professor Marjorie Lawrence. She held summer opera coaching sessions at her ranch, Harmony Hills, which advanced the cause of classical and opera music in Arkansas. A nationally famous program supported by the music clubs dating back to 1950, Opera in the Ozarks at Inspiration Point, includes internationally known tenor Chris Merritt among its alumni. Former Metropolitan Opera star Blanche Thebom came to Little Rock in 1973, along with Ann Chotard, founded the Arkansas Opera Theatre. After she left in 1989, it became the Opera Theatre at Wildwood under the direction of Chotard. Following Chotard’s retirement, the board chose to expand the park’s vision, and opera productions have not resumed. Operas were also produced at the state’s universities. An Arkansas State University music teacher, soprano Julia Langford, who performed with City Opera of New York and many regional companies, frequently featured her students in campus productions. Mezzo-soprano Mignon Dunn of Tyronza (Poinsett County), who appeared 653 times at the Metropolitan Opera, was the wife of Kurt Klippstatter, who conducted the Arkansas Symphony in the 1970s.

Trailblazers in Classical and Opera Music

Classical and opera music may not have achieved the recognition granted more specialized popular forms, but especially notable are the many trailblazers in classical music and opera who have been associated with Arkansas—especially African Americans. Scott Joplin, renowned for his ragtime compositions, wrote his single surviving opera, Treemonisha, with a plot set in Arkansas. William Grant Still of Little Rock completed his Afro-American Symphony in 1930. First performed in 1931 by the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra and still performed today, it is Still’s most well-known composition and was the first symphony composed by an African American that was performed by a major orchestra. Florence Beatrice Smith Price, a graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music who taught at Cotton Plant Academy and Shorter College in Little Rock but was denied membership in the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association, became the first black female composer to have a work performed by a major American symphony when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed her Symphony in E Minor on June 15, 1933.

Robert McFerrin Sr. of Marianna (Lee County), father of singer and conductor Bobby McFerrin, was a baritone opera and concert singer who was the first black male to appear in an opera at the Metropolitan Opera House; his debut came less than a month after the well-publicized breaking of the color barrier by contralto Marian Anderson. More recently, opera mezzo-soprano Gretha Boston of Crossett (Ashley County), who was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 1997, debuted at Carnegie Hall in May 1991 with Mozart’s Coronation Mass. The first Arkansan to receive a Tony Award, she won the 1995 Tony for Best Featured Actress in a Musical for her role as Queenie in the Broadway revival of Show Boat. Juilliard-trained soprano Barbara Hendricks from Stephens (Ouachita County) had an international career in opera and film and performed at jazz festivals. She also has been noted for her work with refugees and for other humanitarian causes. She also performed at a gala for President Bill Clinton’s 1993 inauguration. Soprano Georgia Ann Laster grew up in Arkansas; a branch of the National Association of Negro Musicians is named after her.

Other Arkansan classical and opera musicians who have achieved fame include Mary Lewis of Hot Springs, who made her way to grand opera via vaudeville and operetta. Her career included radio performances and recordings with His Master’s Voice (HMV), Victor, and RCA. Celebrity status was accorded to Mary McCormic—born Mamie Harris in Belleville (Yell County). A graduate of what is now OBU, she sang in Paris, France, and in Chicago, Illinois, and left behind a recorded legacy.

Frances Greer of Piggott (Clay County) and Helena had an extensive vocal career that included The Frances Greer Show on radio, performances with the Metropolitan and Philadelphia Opera companies, and work in operetta and radio. Susan Dunn of Malvern (Hot Spring County), a Hendrix College graduate, was a prominent soprano during the 1980s and 1990s. One of the important names nationally in opera production was UA graduate Sarah Caldwell, who brought opera back to Boston and became the first woman to conduct an opera at the Metropolitan Opera House, on January 13, 1976. Also making a name for herself in opera is soprano Kristin Lewis of Little Rock, who began her vocal studies at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway and performs around the world.

Some other notable Arkansas classical composers, performers, and directors are player-piano composer Conlon Nancarrow of Texarkana; world-renowned composer and conductor Francis McBeth, who was professor and resident composer at OBU and also conducted the Arkansas Symphony for many years; Jett Hitt, an outfitter at Yellowstone National Park who composed Yellowstone for Violin and Orchestra; composer John S. Hilliard of Hot Springs, who is especially known for his piano compositions; the Grammy-nominated New York Philharmonic Orchestra English horn player Thomas Stacy, who grew up in Augusta (Woodruff County); and Buryl Red of Little Rock, who is the musical director and conductor of the CenturyMen choral group. UA professor Bruce Benward wrote the bestselling two-volume book Music In Theory and Practice (1963), which has long been the standard in the field.

For additional information:

Barnwell, RyeAnn. “Frederick Harwood and Henderson State Teacher’s College: A History.” PhD diss., University of Oklahoma, 1987.

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Dougan, Michael B. “Bravo Brignoli! The First Opera Season in Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 30 (Winter 1982): 74–80.

Hudgins, Mary. “Composer Laurence Powell in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1972): 181–188.

Tucker, Jenna M. “A Survey of Professional Operatic Entertainment in Little Rock, Arkansas: 1870–1900.” DMA diss., Louisiana State University, 2010. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3766/ (accessed June 13, 2022).

Michael Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Moorman, Charlotte

Moorman, Charlotte Arkansas Symphony Orchestra

Arkansas Symphony Orchestra  Arkansas Traveler Print

Arkansas Traveler Print  Diamond State Chorus

Diamond State Chorus  "Fayetteville Polka"

"Fayetteville Polka"  Grand Opera House

Grand Opera House  Grand Opera House

Grand Opera House  Barbara Hendricks

Barbara Hendricks  Hollenberg Building

Hollenberg Building  Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin  Marjorie Lawrence

Marjorie Lawrence  Mary Lewis

Mary Lewis  Robert McFerrin Sr.

Robert McFerrin Sr.  Conlon Nancarrow

Conlon Nancarrow  "Ol' Man River," Performed by William Warfield

"Ol' Man River," Performed by William Warfield  Opera House

Opera House  William Grant Still

William Grant Still  Top of the Rock Chorus

Top of the Rock Chorus

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.