calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil War Refugees

The Civil War that beset Arkansas for four years quickly depleted the modest infrastructure and resource base that then existed throughout the young state. The burden of armies supplying themselves with forage and requisitions from civilians compounded with marauding guerrillas and bushwhackers left many citizens utterly destitute, threatened with starvation. During wartime, order was often imposed only by means of military superiority over opposing forces, and civilized society in much of Arkansas began to break down as the fighting wore on. The prospect of survival in a war-torn state turned thousands of Arkansans into refugees who sought the charity of bare sustenance within Union lines or by leaving Arkansas altogether.

Even before the war, Arkansas was bitterly divided from within regarding secession, with most loyal Unionists residing in the Ozark Mountains in northern Arkansas. In this region, slave ownership was significant in select places but nominal in comparison to rich agricultural lands in the Delta and regions farther south. This divided citizenry created the emblematic conditions in which “brother fought against brother,” and much of the state north of the Arkansas River was a patchwork of neighboring communities that swore loyalty to opposing sides. Early Confederate success in Missouri and Union defeat at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in 1861 left wide swaths of northern Arkansas and southern Missouri empty of Union forces, which prompted thousands of threatened Unionist Arkansans to abandon their homes and flee north to Union army encampments in Missouri.

By contrast, many Arkansas slave owners apparently surmised that advancing Union armies would herald emancipation of their slaves and sought refuge in Texas, particularly following the Union victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862. In a personal journal entry dated November 24, 1862, William Williston Heartsill, a member of the W. P. Lane Rangers (Texas Cavalry), made note of this stream of refugees, recording: “Every day we meet refugees with hundreds of Negroes, on their way to Texas; thus we see that as the war is depopulating and ruining this country, it is building up the ‘Lone Star State.’” Some Arkansans who did not own slaves also turned refugee to avoid conscription, only to return to Arkansas later in the war to evade Confederate conscription efforts in Texas.

Except for its adjacency to the Mississippi River, Arkansas was considered of nominal strategic importance to the leadership of both sides during the war. Following its victories at the battles of Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove in 1862, until its disastrous Red River campaign in 1864, Union forces were more frustrated in their efforts at times by poor roads, lack of forage, and guerrilla bands encouraged by Confederate authorities than by organized military resistance. By late 1863, most Union forces in Arkansas and Missouri switched to a defensive posture, as it was apparent that Missouri was safe from Confederate threats. The Union held permanent garrisons at Fayetteville (Washington County) and Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and maintained a “line of defense” that stretched across Missouri from Cape Girardeau to Springfield. This strategy left a minimal Union presence in northern Arkansas, leaving Unionist sympathizers who had fled Arkansas unable to return safely, while those who remained behind suffered from the depredations of guerrilla bands.

Constant foraging by both armies and devastation by guerrillas did their part to drive thousands of Arkansans into destitution, but other factors were involved. The exodus of husbands, fathers, and sons leaving to fight in the war disrupted the annual farming cycles and left women and children to plant and harvest by themselves. Those that did manage to sow and reap crops during the war years often grew cotton instead of sustenance crops in an attempt to recoup economic losses, further reducing available food supplies. On occasion, wheat or corn was successfully harvested, but scorched-earth tactics by combatants, either in retribution or in an attempt to deny materiel to the enemy, resulted in slain livestock and many destroyed grist mills, rendered incapable of producing flour. War-ravaged populations who faced the prospect of starvation and did not or could not flee Arkansas ultimately sought relief and safety from Union garrisons at Little Rock (Pulaski County), Fort Smith, and Fayetteville, among others.

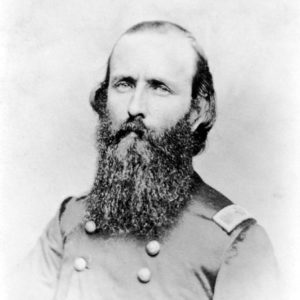

The flood of refugees to Union encampments did yield some positive benefits, as thousands of loyal Union men organized into what ultimately totaled seventeen units of Arkansas regulars that served in the Federal war effort. The first of these units, the First Arkansas Cavalry (US) was organized in 1862 by Colonel Marcus LaRue Harrison, Union garrison commander at Fayetteville. Other able-bodied men were put to work building fortifications and other manual tasks, but the problem of feeding, housing, and protecting refugees was a logistical nightmare that had no prescribed solution and continued to badger Federal commanders for the entire war. As there was no specific remedy regarding feeding and housing, handling of the refugees was left mostly to the discretion of individual garrison commanders. Humanitarian concerns were present in the consideration of how to handle the steady stream of refugees, and private charities were utilized to help with relief and relocation wherever possible, but the sheer number of persons seeking relief left the Union army as the primary provider for these indigent citizens at enormous financial cost to the war effort.

At times throughout the war, some commanders sought to allow refugees to work growing crops on confiscated or abandoned farmland, but Colonel Harrison began in 1864 organizing “post colonies,” which in essence were farms worked by refugee groups of at least fifty men and their families. The settlers—the men of which had to be capable of bearing arms—were to be of known loyalty and to cultivate land tracts, “giving to each one all he wants to cultivate,” within a ten-mile radius of a communal fortification. Legal considerations of land ownership aside, Harrison moved forward implementing the post colonies, citing the need to feed and house refugees to alleviate government expense. Ultimately, Harrison helped establish seventeen colonies in Benton, Madison, and Washington counties, which were inhabited by an estimated 1,200 men, not including family members, and had a projected cultivation of 15,000 acres. Unionist governor Isaac Murphy was also enthusiastic about expanding the post colony program and encouraged Colonel Harrison to establish colonies in other counties, though this never materialized.

Harrison viewed this endeavor as a success in civilizing the region and making refugees self-sufficient, but it was not without detractors. Brigadier General Cyrus Bussey served as garrison commander at Fort Smith from February 1865 onward and was involved in selling rations and supplies to citizens and refugees under his own command. Bussey offered sometimes contradictory objections to the tenability of the post colonies and Harrison’s true intentions behind the program. Bussey cited citizens’ complaints and wrote that Harrison used terror and coercion to force area residents into joining his colonies. Bussey further suspected Harrison of creating a “military despotism,” squandering or liberally giving away government rations, and attempting to run his post colony experiment for his own benefit, possibly for a postwar run for Congress. It is difficult to determine the extent to which Bussey’s investigations and allegations are accurate, but the war in Arkansas ended before the post colony experiments could be fully tested or exemplify their effectiveness in caring for refugees.

Immediately after the war, some Arkansans became refugees for reasons other than mortal peril or destitution. Some Confederate political and military leaders anticipated Northern retribution or imprisonment for their involvement with the Confederacy and fled to Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, British Honduras (modern Belize), and Brazil, among other countries. Some wealthy planters who had managed to retain their slaves until the war’s end continued to do so in Central America and Brazil, where slavery was not yet abolished; other Southerners sought the opportunity to rebuild their lives away from their war-ravaged homes and an occupying Union army. Perhaps the most prominent Arkansas refugee of this class was Brigadier General Thomas Carmichael Hindman of Phillips County, who saw potential in relocating his family to Mexico but returned to Arkansas in 1867.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. “General Bussey Takes Over at Fort Smith.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Autumn 1965): 220–240.

Bradbury, John F., Jr. “‘Buckwheat Cake Philanthropy’: Refugees and the Union Army in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Autumn 1998): 233–254.

Dawsey, Cyrus B., and James M. Dawsey, eds. The Confederados: Old South Immigrants in Brazil. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Hopkins, David P., Jr. “‘A Lonely Wandering Refugee’: Displaced Whites in the Trans-Mississippi West during the American Civil War, 1861–1868.” PhD diss., Wayne State University, 2015.

Huff, Leo E. “Guerrillas, Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Summer 1965): 127–148.

Hughes, Michael A. “Wartime Gristmill Destruction in Northwest Arkansas and Military-Farm Colonies.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 167–186.

Lemke, W. J. “A Christmas Story.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 9 (Winter 1950): 229–230.

Shaw, Arthur Marvin. “A Texas Ranger Company at the Battle of Arkansas Post.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 9 (Winter 1950): 270–297.

Adam Miller

Searcy, Arkansas

Civil War Recruitment

Civil War Recruitment Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Freedmen's Bureau

Freedmen's Bureau Military Farm Colonies (Northwestern Arkansas)

Military Farm Colonies (Northwestern Arkansas) M. LaRue Harrison

M. LaRue Harrison

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.