calsfoundation@cals.org

Union Occupation of Arkansas

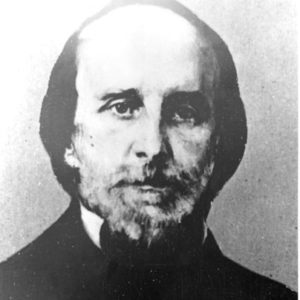

At the Arkansas Secession Convention in May 1861, only Isaac Murphy, among seventy total delegates, refused to repudiate Arkansas’s bonds with the United States. The total delegation was representative of the wishes of many Arkansans, but Unionist sentiment ran deep in some regions, and eagerness for secession was not wholly unanimous among ordinary Arkansans expected to rally to the Confederate cause. During the war, these same ordinary Arkansans were pressed by Union and Confederate armies for conscription and forage, and devastation wrought by irregular partisans hastened a complete breakdown of civilized society in many parts of the state. Union forces were successful in reestablishing law and order as they pushed into Arkansas but were largely restricted to the area around their own garrisons. Federals also achieved mixed results in neutralizing Confederate resistance until the very last days of the war but did enable progress to begin in state reconstruction and in reconciling the newly freed slaves onto paths of citizenship and economic parity with their white neighbors.

Curtis’s March across Arkansas

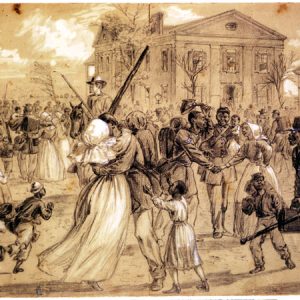

The bulk of Arkansas’s Confederate troops was transferred east to join operations in Tennessee following Union victory at Pea Ridge (Benton County) in March 1862, which consequently left almost no organized military presence to oppose Union incursions. Union major general Samuel Curtis capitalized on this lack of resistance, slowly marching his army eastward to occupy river ports Batesville (Independence County) and Jacksonport (Jackson County) in late spring before taking Helena (Phillips County) in July 1862. In many ways, Curtis’s march across Arkansas foreshadowed General Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea” two years later, as a Union army advanced deep into hostile land, isolated from a line of supply. Union progression into Confederate territory also meant de facto emancipation for thousands of slaves. Even before the official Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln, Arkansas slaves received the opportunity presented by the invading Yankees; those who were able to do so cast off their bondage and flocked to Curtis’s army as it advanced, following it all the way to Helena.

En route to Helena, Curtis’s army was compelled to forage and requisition supplies from civilians, and devastation lingered in the army’s wake. Total war was exacted upon materiel and infrastructure during the march to prevent its use by the enemy; a soldier under Curtis’s command wrote of deserted houses “fast going to ruin; fences are pulled down and burned up; orchards are ruined by hitching horses and mules to the trees; fields are left uncultivated and an air of sickening desolation is everywhere visible.” Both armies were guilty of these practices, however, and local authorities were increasingly unable to maintain peace in the absence of a large armed force to impose some semblance of order.

Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers

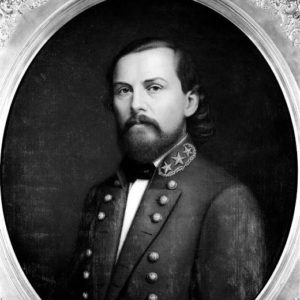

In reaction to Curtis’s march across Arkansas and to prevent the capture of Little Rock (Pulaski County), the Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, Thomas C. Hindman, began initializing “scorched-earth” tactics to deny forage and supplies to Union armies and called upon un-conscripted citizens to organize themselves into guerrilla bands to harass Union forces independent of specific instructions from authorities. Thus, the first officially sanctioned companies of slash-and-burn partisans were formed in 1862. Wherever uniformed regular troops were absent, marauders carried on the fighting on a personal level that frequently ignored the rules and aim of what is known as civilized warfare—as opposed to irregular, or guerrilla warfare.

Guerrilla fighters (popularly dubbed “jayhawkers” or “bushwhackers”) fought for either the Union or Confederate cause, sometimes interchangeably, or sometimes for no cause aside from plunder or revenge. These bands usually consisted of deserting soldiers, men evading conscription, those on self-appointed missions of vengeance, or bandits intent on rape, robbery, or murder. Guerrillas fought in plain clothes, preyed upon enemy forage parties and supply trains, disrupted communication lines, harassed enemy movements wherever possible, and could blend back into the civilian population to escape detection. Some guerrilla bands had legitimate military endeavors, but many did not; and almost all of them ravaged the food, livestock, and property of noncombatants and civilians of differing loyalties.

From a civilian perspective, roving guerrilla bands consumed what meager food and provisions war-torn Arkansas had left after supplying passing armies on the march. Consequently, Arkansas increasingly became a state left in chaos, and most of its citizens had nothing left but poverty and despair. Many fled the state—thousands of loyal northern Arkansans already chose to flee to the safety of Union lines in Missouri in 1861. Pockets of lawlessness that continued to arise statewide caused thousands more to seek safety by fleeing to Kansas, Texas, or the unsettled western frontier.

Establishing a Union Government

The capture of Little Rock by Federal forces in September 1863 afforded Arkansas Unionists the opportunity to establish a loyalist government and set the state on a path of reconciliation with the Union. That December, President Lincoln issued a proclamation of amnesty and reconstruction, more widely known today as the “Ten Percent Plan,” which provided lenient terms by which states could receive executive recognition as no longer being in rebellion. In accordance with this plan, a constitutional convention was held in Little Rock in January 1864 involving delegates representing almost half of Arkansas’s then fifty-seven counties; the constitution drafted at this convention abolished slavery, renounced secession, and changed election guidelines for some state officials but was otherwise similar to the state constitution of 1836. An enumeration of rights for newly emancipated slaves (including Black male suffrage) was noticeably absent from this new constitution, however. The convention appointed state officials on a provisional basis and selected Isaac Murphy as governor, though he abstained from acting in this capacity until after the constitution and his appointment were ratified by popular vote. That March, an election overseen by Union forces was held to ratify the new constitution and governor appointment, although fewer than ten percent of Arkansas voters participated, in part because most of southern Arkansas still remained under Confederate control. Nonetheless, Governor Murphy and the reconstructed constitution were overwhelmingly approved, and the newly elected state legislature appointed Elisha Baxter and William Fishback to the U.S. Senate in May 1864. Both men were refused admittance by the Senate’s Radical Republicans, who were indignant over the perceived forbearing nature of Lincoln’s reconstruction plan.

Stalemate

The effort in establishing a reconstructed Arkansas government in 1864 was concurrent with Union ambitions in delivering a final, decisive blow against remaining Arkansas Confederates. The state Confederate government fled before the capture of Little Rock and eventually relocated to Washington (Hempstead County), ruling in exile and general impotence for the remainder of the war. In what later became known as the Camden Expedition, part of the (ultimately disastrous) Red River Campaign, Union major general Frederick Steele’s army was thwarted in its efforts to advance through southwestern Arkansas and on toward Shreveport, Louisiana. Confederate victories at Marks’ Mills and Poison Spring in April 1864 forced Steele to turn back to Little Rock, and there was a strategic stalemate of sorts in Arkansas until the end of the war. Thereafter, both armies typically limited themselves to cavalry raids into opposing territory, but guerrilla bands continued to inflict the depredations of war. Union garrisons had reestablished order in cities such as Little Rock, Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Fayetteville (Washington County), but guerrillas operated freely outside the reach of Union garrisons. By the thousands, civilians who were unable or unwilling to flee Arkansas ultimately became refugees within their own state, seeking aid and protection from Union forces.

Refugees and Freedmen

For the latter half of the war in Arkansas, Union forces were beset with problems dealing with refugee civilians and newly freed slaves, both before and after official emancipation in 1863. Refugees fled to Union lines seeking relief from exposure and starvation; freedmen likewise left their bondage and sought means of sustaining themselves. Charitable organizations supplied some relief, but the sheer volume of refugees and freedmen meant that the heaviest burden of stewardship fell to the occupying Union armies. For instance, records indicate that, by March 1865, rations given to refugees at Fort Smith, Van Buren (Crawford County), and Fayetteville were equal to those given to garrison troops. A Union departmental policy of refugee relief was formed in April 1865; until that time, individual commanders managed the challenge of feeding and housing noncombatants on their own terms.

In 1864, Colonel Marcus LaRue Harrison, garrison commander at Fayetteville, initiated a unique system of “post colonies,” in which groups of refugee families would farm individual parcels of land near a common fortification for defense against guerrillas. Officials considered the confiscation of land for colony use to be a matter of necessity since the land was farmed in order to feed refugees rather than to provide economic self-sufficiency. Eventually, seventeen post colonies across Benton, Washington, and Madison counties were established, but the war ended before their effectiveness in feeding destitute refugees could be fully measured.

Union leaders quickly realized the benefits and drawbacks of eager slaves, hungry for freedom, flocking to Union lines “wandering around the camp thick as blackberries,” as described by a Wisconsinite serving in Curtis’s army en route to Helena. In August 1862, the U.S. government began instituting contraband camps in parts of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas to provide fugitive slaves with food and shelter. Union forces utilized these camps to recruit thousands of able-bodied African Americans to work in the war effort. The first of six Black Arkansas volunteer regiments was organized at Helena beginning in April 1863. Ultimately, more than 5,500 Black volunteers from Arkansas served with distinction in the Union army and navy and supplied crucial manpower so that forces engaged against Confederates elsewhere would not be needed to fight in Arkansas.

In addition to establishing contraband camps and recruiting fugitive slaves for labor and military muster, the challenge of feeding and housing led to the creation of freedmen’s “home farms,” somewhat like the experimental post colonies in northwest Arkansas. At least four home farms were established during the war, at Little Rock, DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and near Helena. The land for these farms was leased (not confiscated), and the colonies were economically self-supporting through crop sales and depended upon nearby Union detachments for protection. After a few years, only the DeValls Bluff and Pine Bluff farms were ultimately successful, but these experiments did begin to address the issues surrounding the emancipation of slaves. The opportunity for ownership of land and one’s own labor was understood to be fundamental for all free citizens, and the home farm experiments provided a metric of success by which social and economic potential for freedmen could be measured.

For additional information:

Bradbury, John F., Jr. “‘Buckwheat Cake Philanthropy’: Refugees and the Union Army in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Autumn 1998): 233–254.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. 2003.

Huff, Leo E. “Guerrillas, Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Summer 1965): 127–148.

Hughes, Michael A. “Wartime Gristmill Destruction in Northwest Arkansas and Military-Farm Colonies.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 167–186.

Lovett, Bobby L. “African Americans, Civil War, and Aftermath in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Autumn 1995): 304–358.

Shea, William L. “A Semi-Savage State: The Image of Arkansas in the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Winter 1989): 309–328.

Adam Miller

Searcy, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Freedmen's Bureau

Freedmen's Bureau Politics and Government

Politics and Government Celebrating African American Soldiers

Celebrating African American Soldiers  Samuel Curtis

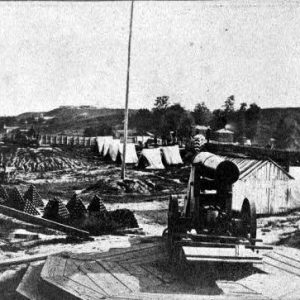

Samuel Curtis  Fort Curtis

Fort Curtis  Thomas Hindman

Thomas Hindman  Isaac Murphy

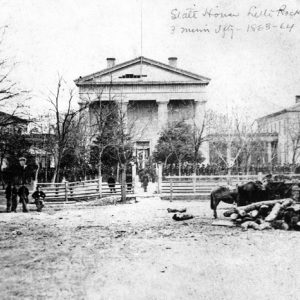

Isaac Murphy  Old State House, Union Occupation

Old State House, Union Occupation  Twenty-Ninth Iowa Volunteer Infantry

Twenty-Ninth Iowa Volunteer Infantry

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.