calsfoundation@cals.org

Unionists

Unionists were Arkansans who remained loyal to the United States after the state seceded from the Union during the American Civil War, often suffering retaliation from Confederate forces and guerrillas. A significant number of Arkansas Unionists served in the Federal army, and loyal Arkansans formed a Unionist government in 1864. Of the more than 111,000 African Americans held in slavery in 1860, the overwhelming majority should be considered Unionists, and thousands flocked to the protection of Union armies at their first opportunity.

As the possibility of disunion arose following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Arkansans were not wholeheartedly in favor of secession. Arkansas had been a state for only twenty-five years and had benefited from the presence of U.S. Army troops, particularly on the border with the Indian Territory, and from such projects as a swamplands reclamation project in the Arkansas Delta region and federal support for nascent railroad projects. Only around twenty percent of the state’s white population owned slaves, leading some to question the need to protect the human property of that minority. And many of the state’s political and opinion leaders felt that the Constitution and the federal court system would protect Arkansas and its people against any excesses from the new Republican Party.

Historian Christopher Phillips categorized two general classifications of Unionists in the states considering secession. The first were unconditional Unionists, “generally antislavery Republicans or Old Line Whigs.” Second were conditional Unionists, “moderates who advocated staying in the Union so long as the federal government did not interfere with a state’s right to determine local affairs.” The vast majority of Arkansas’s Unionists numbered among the latter—people historian James M. Woods described as Unionist-Cooperationists—and included many who owned slaves or who feared the negative impacts a civil war would have on Arkansas’s society and economy.

When Arkansas voters elected on February 18, 1861, to hold a secession convention, forty of the seventy-five delegates sent to argue the issue in Little Rock (Pulaski County) were Unionist in their tendencies, many hailing from Arkansas’s northern and western counties. They elected David Walker of Fayetteville (Washington County), a slave-owning Unionist and former Whig, as the convention chairman, and when the vote on secession was finally held it was defeated thirty-nine to thirty-five. After Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, and Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers to suppress the rebellion, Walker recalled the delegates on May 6. An initial vote showed five of the seventy delegates opposed to leaving the Union; after a second vote held to show unanimity in Arkansas, only Isaac Murphy of Huntsville (Madison County) maintained his Unionist stance.

The strength of Unionist sentiment in the state was apparent from the beginning, as Confederate authorities discovered a secret Unionist organization in mountainous northern Arkansas. As many as 1,700 men may have belonged to the Arkansas Peace Society, and hundreds of them were arrested. Some were forced to join the Confederate army, while others fled to Missouri to join Union regiments in that divided state. Civilian Union sympathizers throughout Arkansas would face persecution by both Confederate forces, irregular troops, and bushwhackers throughout the war, leading many to abandon their homes and property.

Northwestern Arkansas Unionists sought the protection of the federal Army of the Southwest when it marched into Arkansas in February 1862 before the Battle of Pea Ridge, and when Major General Samuel Curtis reentered Arkansas in May 1862, he found on reaching Batesville (Independence County) that there were many Unionists in the region; some, including many avoiding conscription into the Confederate army, joined Union forces and accompanied them when they marched into Helena (Phillips County) in July.

Similarly, Arkansas’s African-American population turned to the protection of Union armies as they operated within Arkansas. General Curtis took the extraordinary step of emancipating slaves during the Army of the Southwest’s march toward Helena in the summer of 1862, and more than 3,000 African Americans followed the federals into the Mississippi River town, where so-called contraband camps were thronged by slaves from Arkansas and Mississippi seeking freedom. This was replicated in every major movement of Union troops within the state for the rest of the war, and camps were established in Union-controlled areas to accommodate them.

As the war progressed, white dissatisfaction with the Confederacy increased in Arkansas as food ran short, inflation ravaged the economy, and a policy enacted wherein one white man could be exempted from conscription for every twenty or more slaves on a plantation created a clear class division. On January 6, 1863, as many of fifty conscripts at a camp in Magnolia (Columbia County) marched out, refusing to serve in the Confederate army. Throughout southwestern Arkansas, Unionists organized militarily and politically, with bands of armed Unionists reported in Clark and Pike counties and Union Leagues organized in Clark, Pike, and Calhoun counties. Confederate lieutenant general Theophilus Holmes declared martial law on February 9, 1863, and troops were sent into the region to crush the partisan bands, including a force that was attacked and devastated at McGraw’s Mill, survivors of which made their way north to join Union regiments. Ringleaders of the Calhoun County Union League were arrested, and at least three were hanged. So many Unionists were forced into the Confederate army in western Arkansas that, at the September 1, 1863, Action at Devil’s Backbone in Sebastian County, about one-third of the Confederate force simply fled the battlefield, with several hundred joining the Union army shortly afterward. Union militancy was also recorded in Sebastian, Logan, and Yell counties.

Unionists provided substantial military support to the Federal army in Arkansas. White Arkansas Unionists, beginning with refugees in Missouri who formed the First Arkansas Cavalry (US) in 1862, organized regiments to serve in the Federal army, with some 8,789 men serving in four cavalry regiments, ten regiments or battalions of infantry, and two light artillery batteries. Others fought in Missouri regiments or in partisan bands such as that of Jeff Williams in Conway County. Arkansas had the highest number of native sons fighting for the Union in any of the seceded states with the exception of Tennessee. One in every seven white Arkansas men of military age served in Union regiments, according to historian D. D. McBrien. Black Arkansans, too, enlisted in the Union army after they were authorized to do so in 1863, with a total of 5,526 credited to Arkansas units. Of these, some 1,700 white and 1,500 black Arkansans would die in Federal service.

As Federal troops established a presence in Arkansas with the occupation of Little Rock in September 1863 and the formation of fortified posts along the Arkansas River Valley, Unionists in areas controlled by the Confederate government or in areas infested with bushwhackers fled to the safety of the strongholds, causing considerable hardship in the post at Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and residents of the occupied cities took the oath of loyalty to the United States, as they had earlier in the war at posts controlled or occupied by U.S. troops. In northwestern Arkansas, Unionist civilians with military support established twenty-one military farm colonies in the spring of 1864 to enable more than 1,000 men and their families to raise crops and protect their property from guerrillas. Similar attempts were made by white and black Unionists in the Delta region in 1863 and 1864, though with less success.

Unionists living in areas outside of Union control faced harassment or worse from Confederate forces or pro-Southern guerrillas, with houses burned, property stolen and many who remained loyal to the Union murdered. Federal forces sent regular patrols out in search of the bushwhackers, who would face stern justice if captured. On March 18, 1864, for instance, Jeremiah Earnest of Montgomery County and Thomas Jefferson Miller of Hempstead County were hanged at the penitentiary in Little Rock for the murder of three Unionists, including seventy-year-old Elijah Osborn, who reportedly told his killers, “When you hang me, you will hoist a Union flag.”

After President Lincoln announced a plan that any seceded states could establish a loyal government once ten percent of the people who had voted in the 1860 election had professed their loyalty, Unionists in Arkansas moved to establish a new state government in Little Rock. Major General Frederick Steele on February 2, 1864, designated posts at Helena, Little Rock, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Fayetteville, Van Buren (Crawford County), Dardanelle (Yell County), Lewisburg (present-day Morrilton in Conway County), DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), and Batesville as sites where Arkansans could take the oath of allegiance. Led by such men as William Fishback, Elisha Baxter, Edward W. Gantt, and Isaac Murphy, Unionists moved to hold a constitutional convention that would nullify the Confederate state constitution and abolish slavery. An election of somewhat dubious integrity was held March 14–16, 1864, and Arkansans voted 12,177 to 266 to approve the new constitution and make Isaac Murphy, who had been serving as provisional governor, the permanent governor of Arkansas; he was inaugurated on April 18. The new Unionist government accomplished little other than the April 1865 vote for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Many of its members went on to serve prominent roles during Reconstruction in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Bradbury, John F., Jr. “‘Buckwheat Cake Philanthropy’: Refugees and the Union Army in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Autumn 1998): 233–254.

Britton, Nancy. “E. D. Rushing: A Unionist in Independence County during the Civil War.” Independence County Chronicle 55 (July 2014): 19–37.

Christ, Mark K. “‘They Will Be Armed’: Lorenzo Thomas Recruits Black Troops in Helena, April 6, 1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Winter 2013): 366–383.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

———. “All Cut to Pieces and Gone to Hell”: The Civil War, Race Relations, and the Battle of Poison Spring. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

Cowen, Ruth Caroline. “Reorganization of Federal Arkansas, 1862–1865.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 18 (Summer 1959): 32–57.

DeBlack, Thomas A. “‘A Surprisingly Strong Union Sentiment’: Unionism in Arkansas in1861.” in The Die Is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861, edited by Mark K. Christ. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

Duncan, Georgena. “Uncertain Loyalties: Dual Enlistment in the Third and Fourth Arkansas Cavalry, USV.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Winter 2013): 305–332.

Howard, Rebecca. “Civil War Unionists and Their Legacy in the Arkansas Ozarks.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2015. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1426/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

———. “No Country for Old Men: Patriarchs, Slaves, and Guerrilla War in Northwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Winter 2016): 336–354.

Hughes, Michael A. “Wartime Gristmill Destruction in Northwest Arkansas and Military Farm Colonies.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 167–168.

Johnston, James J. Mountain Feds: Arkansas Unionists and the Peace Society. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Jones, Kelly Houston, “The Peculiar Institution on the Periphery: Slavery in Arkansas.” PhD dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 2014.

McBrien, D. D. “Arkansas Unionists.” Arkansas Valley Historical Papers 24 (March 1962): 1–12.

Moneyhon, Carl H. “Disloyalty and Class Consciousness in Southwestern Arkansas, 1862–1865.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Autumn 1993): 223–243.

———. “From Slave to Free Labor: The Federal Plantation Experiment in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer 1994): 137–160.

———. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Phillips, Christopher. The Rivers Ran Backward: The American Civil War and the Remaking of the American Middle Border. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Rein, Christopher Michael. “Trans-Mississippi Southerners in the Union Army, 1862–1865.” MA thesis, Louisiana State University, 2001. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/748/ (accessed June 13, 2022).

Robertson, Brian K. “Men Who Would Die by the Stars and Stripes: A Socio-Economic Examination of the 2nd Arkansas Cavalry (US).” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Summer 2010): 117–139.

Scott, Kim Allen, ed. Loyalty on the Frontier, or Sketches of Union Men of the South-West with Incidents and Adventures in Rebellion on the Border. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Woods, James M. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Mark K. Christ

Little Rock, Arkansas

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Union Occupation of Arkansas

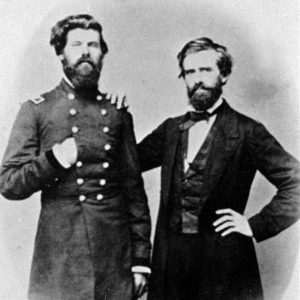

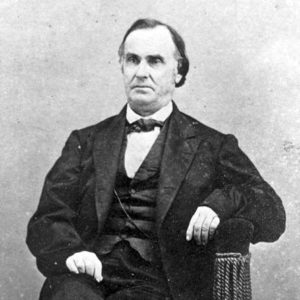

Union Occupation of Arkansas Elisha Baxter

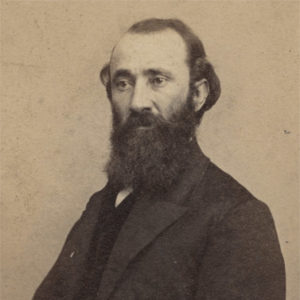

Elisha Baxter  William Fishback

William Fishback  Edward Gantt

Edward Gantt  Augustus Garland

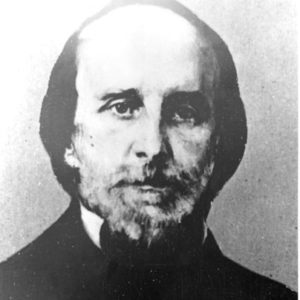

Augustus Garland  Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy  Jonas Tebbetts

Jonas Tebbetts  David Walker

David Walker  Jeff Williams

Jeff Williams

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.