calsfoundation@cals.org

Bill Dickey (1907–1993)

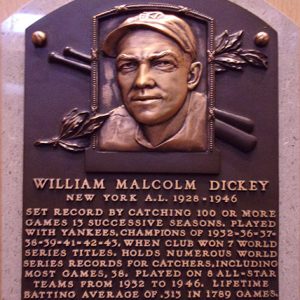

aka: William Malcolm Dickey

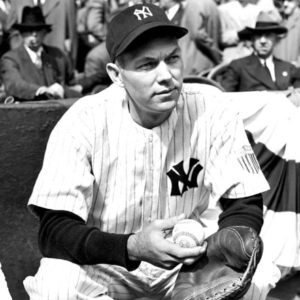

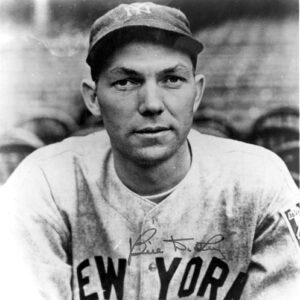

William Malcolm (Bill) Dickey is considered by baseball historians to be one of the best catchers in baseball history. Dickey played and later coached for the New York Yankees during that club’s dominance from the late 1920s to the early 1960s. His years as a player and coach are seen as a bridge that connects the great Yankees teams of those years. It is doubtful that any baseball figure can match the team success Dickey enjoyed as a player and coach. Combined, player/coach Dickey’s teams won seventeen American League titles and fourteen World Series (and Dickey was named to eleven All-Star teams in his playing career). That team success combined with Dickey’s individual performance made for an extraordinary career.

Bill Dickey was born on June 6, 1907, in Bastrop, Louisiana, one of seven children of John Hardy Dickey, a railroad worker, and Laura Ann Chapman Dickey. The family moved to Kensett (White County) three years later and to Little Rock (Pulaski County) when Dickey was fifteen. A younger brother, George “Skeets” Dickey, also became a major league catcher. George Dickey played for the Chicago White Sox and the Boston Red Sox in a six-year career scattered through the 1930s and 1940s.

Bill Dickey played for Little Rock College, a Catholic college, in 1925 and for a semipro team in Hot Springs (Garland County). A scout for the St. Louis Cardinals was sent to Hot Springs to sign the young catcher, but the scout’s car had a flat tire. The delay allowed Lena Blackburne, manager of the Little Rock Travelers, to sign Dickey before the scout arrived. This was an era when any team—not just major league teams—could sign players to contracts. Dickey split the 1926 season between the class C Muskogee Athletics in the Western Association and the class A Southern Association’s Little Rock Travelers. In 1927, the Travelers lent the catcher to the Jackson Senators, a Mississippi team in the class D Cotton States’ League.

Because the Little Rock club had a working agreement with the White Sox, most major league teams assumed Dickey had signed a contract that gave the White Sox the option of buying it. Such an arrangement was common during much of baseball’s history. But Dickey had not signed such a deal, and Chicago failed to press any advantage it might have had with the Travelers. A New York Yankees scout was not so hesitant. After watching Dickey play, the scout urged his bosses to buy Dickey’s contract, saying, “I will quit scouting if this boy does not make good.”

After buying Dickey’s contract, the Yankees assigned him to the Travelers for the 1928 season, bringing him to New York late in the season. Dickey was the Yankees’ regular catcher beginning in 1929, batting .324 his rookie year.

At just under 6’2″ and 185 pounds, Dickey was large for a catcher of his time. This may have helped his durability as well as his hitting. Dickey caught more than 100 games for a record thirteen straight seasons and combined that stamina at a demanding position with a lifetime batting average of .313. Dickey batted more than .300 in eleven seasons with a career high average of .362 in 1936, the highest batting average ever for a catcher. He struck out only sixteen times in 1936. Infrequent strikeouts were a characteristic of his career, as was his ability to get a hit in a key situation.

While Dickey excelled at two of the skills desired in a catcher—durability and hitting—he was equally known for his defense, throwing arm, and the art of knowing how to pitch batters to get them out. In 1931, he became the first catcher in history to go an entire season with no passed balls. He was also one of the first catchers to adopt a one-handed catching technique, a technique more difficult in Dickey’s day due to the smaller, less flexible catcher’s mitts in use then.

Durability and hitting ability were also traits of Dickey’s best friend and roommate on Yankees road trips, Lou Gehrig. The men shared other traits, as well. Both were quiet, reserved gentlemen in a game populated by brasher types. Through their deportment on and off the field, the two instilled a sense of professionalism in the New York club and acted as a counterweight to Babe Ruth’s more boisterous ways. The closeness of the two was evidenced by the fact that Dickey was the only player invited to Gehrig’s wedding and that Gehrig told Dickey, before telling other teammates, about the illness that prematurely ended his career and took his life.

Dickey’s mild manner made a 1932 incident very out of character. After he collided at home plate with Washington player Carl Reynolds as Reynolds tried to score, and believing Reynolds was headed toward him, Dickey landed a punch. He broke Reynolds’s jaw. Dickey was suspended for a month and fined $1,000, both heavy penalties at the time. Another 1932 event was more pleasant: Dickey married Violet Arnold after the baseball season. They had a daughter the next year.

In 1944, Dickey joined the navy and missed the 1944 and 1945 seasons. He returned to play in 1946. Disagreements between veteran manager Joe McCarthy and a new ownership and general manager for the club led to McCarthy’s firing early in the 1946 season. Dickey was named manager, and he curtailed his own playing time the rest of the year. But Dickey had his own disagreements with the front office and resigned as manager in the season’s closing days. His resignation also ended his playing career.

The 1947 season saw Dickey return to the Little Rock Travelers as their manager. After a 51-103 record, Dickey resigned that managerial post. He returned to baseball in 1949, when he joined the coaching staff of the new Yankees manager, Casey Stengel. One of Dickey’s first assignments was to train a young catcher, Yogi Berra, or as Berra told reporters, “Bill is teaching me his experience.” Berra later broke Dickey’s franchise record for home runs by a catcher and his World Series record for number of games played by a catcher. Dickey remained one of Stengel’s coaches through the 1957 season. He served as a Yankees scout in 1959, and he returned to Stengel’s coaching staff briefly during the 1960 season.

Dickey was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1954. In 1959, he was one of the first five sports figures inducted to the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. In 1972, the Yankees retired uniform number 8 in honor of Dickey’s and Berra’s careers, the only time a team has retired a number to honor two players.

Dickey had the distinction of playing himself in two movies. Pride of the Yankees (1942), starring Gary Cooper, was about Gehrig’s life, and The Stratton Story (1949), starring Jimmy Stewart, was about Chicago White Sox pitcher Monty Stratton.

After his baseball career, Dickey joined his brother George at Stephens, Inc., a Little Rock investment firm. A stroke in 1989 left Dickey homebound. He died on November 12, 1993, and is buried in Little Rock’s Roselawn Cemetery.

The new baseball park for the Arkansas Travelers which opened in 2007 was named Dickey-Stephens Park to honor the Dickey brothers and the Stephens brothers—Witt (founder of Stephens, Inc.) and Jack (longtime chief executive officer). Warren Stephens, Jack’s son and chief executive officer of the company, donated land for the park. He named the facility for the four brothers who had shared a friendship and a love of baseball.

For additional information:

Appel, Marty. “Rugged Dickey.” Memories and Dreams 2 (Summer 2004): 10–12.

Honig, Donald. The Greatest Catchers of All Time. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown, 1991.

Lensing, Eric G. “Bill Dickey—New York Yankee.” Pulaski County Historical Review 47 (Winter 1999): 83–91.

Rogers, Thomas. “Bill Dickey, the Yankee Catcher and Hall of Famer, Dies at 86.” The New York Times. November 13, 1993, p. 30.

Williams, Nancy A., ed. Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Bob Razer

Bill Clinton State Government Project

Central Arkansas Library System

Bill Dickey Plaque

Bill Dickey Plaque  Bill Dickey

Bill Dickey  Bill Dickey

Bill Dickey

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.