calsfoundation@cals.org

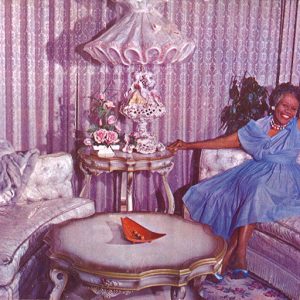

Willa Saunders Jones (1901–1979)

Willa Saunders Jones grew up in Little Rock (Pulaski County) during the first decades of the twentieth century before moving to Chicago, Illinois, where she became a prominent religious and cultural leader. Her crowning achievement was a passion play (a dramatization of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection), which she wrote in the 1920s and produced for more than five decades in churches and eventually prestigious civic theaters. The play featured top musical talent, including Dinah Washington and Jones’s close friend Mahalia Jackson, and drew support from such prominent figures as the Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr. and Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley. Her success in music as a soloist, accompanist, and choral director and in drama stemmed from early experiences in the African-American community of Little Rock and represented the dynamic cultural exchange between the urban South and North.

Willa Saunders was born in Little Rock to Ada Pulliam and George Washington Saunders on February 22, 1901; she had a twin sister who died in infancy and a half-brother. She grew up guided by a close-knit group of relatives in neighboring homes on the southwest side of the city. Her grandfather Joseph Davis was a charter member and prominent official of the Mosaic Templars of America, and her father served as pastor of First Baptist Church-Highland Park. Under his leadership, the church grew, and his position on the Home Missions Board of the National Baptist Convention, USA, offered his daughter early exposure to the denomination’s organizational power. While socially situated in the black middle class, Saunders grew up poor. She learned to play piano on a piece of cardboard with charcoal-drawn keys, receiving instruction from a white neighbor girl.

Saunders attended Stephens Elementary School, graduating from the eighth grade with honors. She entered Arkansas Baptist College, where her father had previously taught, and took a wide range of liberal arts courses. Around the time she graduated with the equivalent of a high school diploma from Arkansas Baptist, she married her childhood sweetheart, George Washington Jones, who attended Philander Smith College. The couple put themselves through school by living with relatives and working menial jobs. Prior to the birth of their first child, George Jr., in January 1921, Jones worked at a laundry. Her husband earned enough at a lumberyard to afford regular payments on a house in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), into which the young family planned to move. The couple later had a second son, Charles, as well as a daughter, Betty Jane, who died soon after birth.

Jones lived in Little Rock when the city was a hub of black middle-class cultural activity. Influential composers William Grant Still and Florence Price were developing their craft, Carrie Still Shepperson (Still’s mother) was producing various dramatic works, and Charlotte Andrews Stephens—the pioneering and widely respected black educator after whom Jones’s primary school was named—was introducing local black citizens to community theater and the fundraising possibilities of music and drama. Mattie Albert Booker Pearry, the daughter of Arkansas Baptist College president Joseph A. Booker, probably had a more immediate influence on Jones than any other cultural leader. Through Sunday afternoon “community sings” at the school, Jones witnessed the power of spirituals and anthems to move both black and white audiences.

An unfortunate series of events foiled the Joneses’ plan to move into their new home in North Little Rock. In March 1921, a white woman claimed that two black men had assaulted her, with one raping her. In Jones’s presence, a vigilance committee entered her home and later strip-searched George Jones and his friend Emanuel West. When the alleged victim later identified West as the rapist, George Jones became the primary witness in a trial that garnered national media attention. Fearing those who attempted to lynch West, the Joneses fled Arkansas, although George Jones returned to defend his friend in court. (In spite of overwhelming evidence in favor of his innocence, and after a highly publicized initial trial that ended in a hung jury, a second jury sentenced West to life in prison, though Governor John E. Martineau later pardoned him.)

In Chicago, Willa Saunders Jones became a teacher and cultural leader similar to Pearry, Shepperson, and Stephens, signaling the significance of her Arkansas upbringing. By the 1930s, she sang with elite sacred choral groups and played organ for several Baptist churches. In 1933, Jones took the solo lead on Price’s choral work “Banjo Song” before a large interracial audience at Chicago Orchestra Hall. In the 1940s and 1950s, she directed massive choruses across the country for the National Baptist Convention. Nothing brought greater acclaim and buttressed her religious authority more than the passion play. George Jones played the role of Christ for more than thirty years until his death in 1965, while she produced and directed the play until her death on January 15, 1979.

For additional information:

Hallstoos, Brian. “Pageant and Passion: Willa Saunders Jones and Early Black Sacred Drama in Chicago.” Journal of American Drama and Theatre 19 (Spring 2007): 77–97.

———. “Willa Saunders Jones.” In African American National Biography, Vol. 5, edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

———. “Windy City, Holy Land: Willa Saunders Jones and Black Sacred Music and Drama.” PhD diss., University of Iowa, 2009. Online at http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/371 (accessed February 1, 2022).

“Passion Play: Annual Chicago Presentation of All-Negro Religious Play Proves Big Box Office Draw.” Ebony (May 1950): 25–28.

Brian Hallstoos

Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Willa Saunders Jones

Willa Saunders Jones

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.