calsfoundation@cals.org

Pearl Rush

The rivers of northeast Arkansas once teemed with freshwater mollusks capable of producing pearls, which led to a huge “pearl rush” in the region in the late 1800s. The mussels had not been harvested on a large scale since Native Americans dwelled along these rivers, giving the animals—and the pearls within—time to grow. In an era before cultured pearls, these gems only occurred naturally, growing inside a freshwater mollusk or saltwater oyster, and the rarity of this occurrence made them precious.

Native Americans used pearls to indicate elite status through adornment and burial practices. Burial sites in Campbell, Missouri, and Spiro, Oklahoma, revealed large quantities of freshwater pearls heaped in baskets or large shell vessels. A grave near present-day Helena-West Helena (Phillips County) contained a pearl bracelet, and Sallie Walker Stockard’s The History of Lawrence, Jackson, Independence and Stone Counties of the Third Judicial District of Arkansas (1904) mentions freshwater pearls found in burial mounds along the White River. As far back as the early 1700s, the geographical area now known as Arkansas was mentioned as a premier pearling location. Daniel Coxe chronicled his travels through present-day southeastern United States and witnessed Native Americans roasting freshwater mussels for food and finding pearls—although the heat from the fire ruined them.

In the mid-1800s, a pearl rush began in northern New Jersey when a shoemaker found a pearl that fetched a small fortune. This discovery set off a frenzy from New Jersey through the Ohio River Valley and down the tributaries of the Mississippi River. It was a time when land had not fallen under the wide and restricted private ownership that would, today, prevent people from accessing waterways. With few tools needed to harvest the mollusk, men, women, and children of all socio-economic levels joined the hunt for treasure. At first, the mussels were so abundant that people could just walk into shallow water and pick them up with their bare hands.

In 1888, a twenty-seven-grain, pear-shaped pink pearl was taken from the White River. In 1895, on the same river, a survey party found $5,000 worth of pearls. This predates the 1897 date generally attributed to the first pearl find by Dr. J. Hamilton Meyers of Black Rock (Lawrence County). News of the discovery of that stunning, fourteen-grain pink pearl set off the Arkansas pearl rush.

Northeast Arkansas became famous as a great spot for pearling. As mussel populations became extensively harvested, tools and boats were necessary to collect them. A strong man in a steady boat could use a long-handled set of tongs called a pearling rake to haul mussels out of deeper water. Subsequent harvest methods included brailing boats and underwater dive gear, although these methods were largely used when the shell was the primary product—with an eye kept out for pearls.

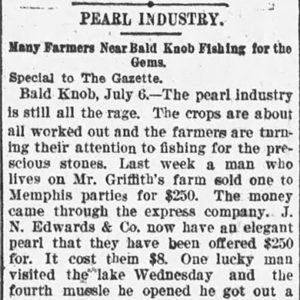

Shanties and tents sprang up along the rivers, largely the White and Black, in the initial rush (1897 to approximately 1903), as people destroyed thousands of mussels attempting to find a single perfect pearl. Some stories hold that because everyone was down at the rivers looking for pearls, crops went unharvested and shopkeepers could not find people to work in stores. Buyers traveled by train from New York and San Francisco, California, while local buyers included John L. Evans, who bought and sold pearls in Batesville (Independence County). Evans was also known to be skilled in peeling pearls, a process whereby an unattractive outer layer was peeled back to reveal a more lustrous gem within.

Discoveries could be accidental, as happened when a fisherman in need of bait opened a mussel and happened upon a gem, while others were well-planned expeditions. One account tells of four men who ordered pearling rakes from a blacksmith and set up camp. They had lumber delivered to their camp, built a boat, and drilled a freshwater well—and their expedition eventually yielded a gigantic pearl. Families went on summer pearling vacations hoping to find treasure but enjoying the festive atmosphere regardless of whether or not a gem was discovered. The rush had dwindled by 1905, but pearls were still found occasionally—as they are today.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the freshwater mussel shell was used in the mother-of-pearl button industry, and in the latter half of that century, the shell was ground into round nuclei and inserted into marine oysters, most often in Japan. The animal’s natural tendency to layer nacre around the bead forms cultured pearls.

Arkansas’s pearl rush provided the setting for the 1989 historical romance novel Delta Pearl, written by Antoinette Bronson and Maureen Woodcock under the pen name Maureen Bronson and published by Harlequin Books.

For additional information:

Craig, Robert D. “Pearling, the Arkansas Klondike.” Stream of History 47 (August 2014): 3–16.

McLeod, Walter. Centennial Memorial History of Lawrence County. Walnut Ridge, AR: Lawrence County Historical Society, 1980.

Shoults, Lenore. “Mother-of-Pearls: The Entwined History of Shell and Pearl in Arkansas.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2010.

Stockard, Sallie Walker. The History of Lawrence, Jackson, Independence and Stone Counties of the Third Judicial District of Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Democrat Co., 1904.

Lenore Shoults

Mountain View, Arkansas

Button Blank Industry

Button Blank Industry Pearl Boats

Pearl Boats  Pearling Camp

Pearling Camp  Pearlers

Pearlers  Pearling Article

Pearling Article  Pearling Industry Barges

Pearling Industry Barges  White River Pearls

White River Pearls

My uncle Sam Kirchner, his father Marion Kirchner, my grandfather Euclid Ogden, and his brother Jesse Suler pearled in the White River in the early 1900s. Uncle Sam used to tell me stories about pearling. He said Marion found an 80 mm pearl and sold it for $500 to a man who came from Memphis to buy the pearl. Sam said he also found a 30 mm pearl he sold for $300. My grandfather, Euclid Ogden, was the person who “cooked them out.” He apparently sold some of the pearls without splitting the profit. It caused a terrible fight between him and his brother. Sam Kirchner was married to my aunt Myrdle Ogden. My father was born in Newport, Arkansas.