calsfoundation@cals.org

Desegregation of Van Buren Schools

The desegregation of Van Buren (Crawford County) schools produced several national headlines and is one of Arkansas’s most intriguing episodes of compliance with—and defiance against—the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas school desegregation decision.

In 1954, the Van Buren School District had 2,634 white students and eighty-seven African-American students. Black students attended a segregated elementary school, and after graduation they were bussed over the Arkansas River to the segregated Lincoln High School of Fort Smith (Sebastian County). After Brown, with assistance from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), nineteen parents sued for the entry of twenty-four black students into Van Buren’s white high school, the first case of its kind in Arkansas. On November 2, 1955, the school board voted to fight the NAACP’s lawsuit.

At the trial, Van Buren superintendent of schools Everett Kelley told the court that it would “take time to educate school patrons for integration,” and that he did not “intend to integrate until forced or until the feeling in Van Buren changes.” Federal District Judge John E. Miller warned that after Brown the only issue was how long the “transition to a racially non-discriminatory school system” would take. Miller ordered the board to produce an integration plan and report back to the court.

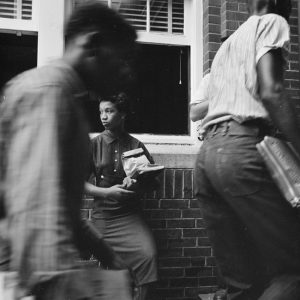

On August 20, 1956, the school board submitted a nine-year desegregation plan beginning in August 1957. Under the plan, the first four high school grades would desegregate in 1957, the eighth grade in 1958, and the seventh grade in 1960. On August 28, 1957, the school board implemented this plan by enrolling twenty-three African-American students with 550 white students. No trouble was reported.

Van Buren High School remained successfully integrated even as the crisis over the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County) unfolded. But because of continuing unrest in Little Rock, the mood changed considerably the following year on September 2, 1958, when thirteen black students attempted to enroll. In contrast to peaceful integration in 1957, black students were met by jeering white students carrying signs reading, “Niggers, Go Home” and “Chicken Whites Go to School With Jigs.”

For four days, around forty white students staged a strike outside the school. On the third night, they burned an effigy of an African-American student on the school grounds. Using the pseudonym Roger Williams, the group sent a telegram to Governor Orval E. Faubus telling him, “In behalf of [sic] Van Buren High School we are on strike here. In order to stay integration, we need your help.” There was speculation that Faubus might use legislation passed by an extraordinary session of Arkansas General Assembly in 1958 to close a school that encountered problems because of desegregation.

School officials were in no doubt about the cause of the disturbances. “If it hadn’t been for Little Rock, we wouldn’t have this trouble now,” one said. “We had Negroes in the school last year—more than this year—and we didn’t have any trouble.” Others agreed. A member of the student council claimed that the strikers were “just trouble makers…They’re always into something and now they’re just trying to imitate Little Rock.” A mother of one of the white students told reporters that Little Rock “gave us an example up here,” adding, “All we needed was something to get it started. And now that it’s started, we’ll soon have those colored children out of there.”

With black students refusing to return to school until their safety was assured, the white students ended the strike. At the next school board meeting, president of the newly formed Van Buren Citizens’ Council (VBCC), Sam Cox Jr., claimed they had nothing against African Americans but added, “We just want them to go to their own schools.” Parents demanded to know why the Van Buren School Board was not seeking a delay in its integration plan in the courts as the Little Rock School Board was doing in the state capital. Fifteen-year-old president of the student council Jessie Angelina “Angie” Evans said that a poll of 160 students in the school favored admitting African-American students, with eighty-five for, forty-five against, and thirty undecided. Afterward, Evans told a Time magazine reporter, “Someone had to speak up. I just don’t think segregation is a Christian thing.”

On Monday, September 8, 1958, NAACP southwest regional attorney U. Simpson Tate asked Judge Miller to hold the Van Buren School Board in contempt of court for failing to implement its desegregation program. Miller refused on the grounds that he had already dismissed the original case when school officials agreed to implement a desegregation plan. He told Tate to file a new suit.

On Friday, September 19, 1958, Judge Miller turned down the request of the NAACP to intervene in events at Van Buren. He expressed confidence that black students could now safely resume classes. On September 22, eight of the thirteen black students returned to school without incident. The next day, one white student, fifteen-year-old Eugene Matthews, told Everett Kelley that black student Nathaniel Norwood had spat at him. Norwood denied this. He claimed that a group of ten white boys had in fact spat at him. Kelley asked Matthews to report to his office that afternoon; backed by his twin brother, Gene, he refused. Kelley suspended both indefinitely.

The VBCC responded by circulating petitions for the recall of school board members. School board president J. J. Izard, whose seat was targeted by segregationists, explained that the school board had no choice under existing law but to desegregate. Izard stepped down before the election, and his place on the school board was contested by Sam Cox Jr. and local businessman Russell Myers. Myers took the position in the election that he was against integration but for keeping the schools open. He won by 1,084 votes to 256 votes. The school remained integrated, and the VBCC disbanded.

For additional information:

Clemons, James T., and Kelly L. Farr, eds. Crisis of Conscience: Arkansas Methodists and the Civil Rights Struggle. Little Rock: Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, 2007.

“Courage in Van Buren.” Time, September 22, 1958, p. 14.

“Hoodlums in Arkansas.” Time, September 15, 1958, p. 15.

Kirk, John A. “Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954–1966.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (August 2011): 225–257.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) Van Buren Desegregation

Van Buren Desegregation

I was a student at Van Buren High School, graduating in 1960. The so-called strike in 1958 involved a handful of white students, 1015. MOST of us attended classes. The strike was blown out of proportion by Time and Life magazines. There was more disruption for students in 1957 when the Arkansas National Guard was activated and then federalized, causing some of the older students who were members the Guard to be late to class because they had to report to the armory before class. In Sept. 1958, the strikers circled the high school in their cars with signs and shouts, performing for the TV and magazine reporters. Most of us stood in line awaiting the first bell and went to class after it rang. As for the strikers, those of us non-strikers considered them non-students who were looking for a reason to not attend classes. Douglas Elementary school in Van Buren was a disgrace. Lincoln High School in Fort Smith was not much better. The students from those schools were not prepared for classes in Van Buren High School due to the lower level expected in the black schools. Their difficulty was due to lack of preparation, not their ability. One of my classmates was the president of the student body and stood up to the reporters. She was/is one of my friendsa hero for her action in stopping the so-called strike. Everett Kelly and J .J. Izard were personal friends during all of this. Mr. Izard was my fathers boss. Upon graduation in 1960, Mr. Izard handed me my diploma and later a personal gift. I knew the Norwood family outside of school; Mrs. Norwood cleaned our home. Many times I picked her up at her home and returned her after her work.