calsfoundation@cals.org

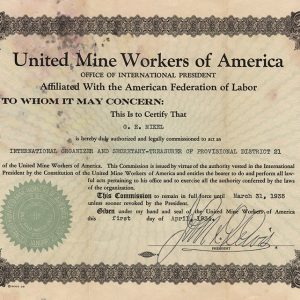

United Mine Workers of America (UMWA)

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was at one time the most powerful union in the United States. The union, which remains active in the twenty-first century, encouraged the development of the Arkansas State Federation of Labor.

The UMWA was formed in 1890 in Columbus, Ohio, when Knights of Labor Trade Assembly No. 135 merged with the National Progressive Union of Miners and Mine Laborers. This combined union banned discrimination against any members based on race, national origin, or religion. By 1898, the UMWA had achieved improvements in wages and hours per week with mine operators in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

In 1898, the UMWA began organizing miners in western Arkansas. Arkansas became a part of District 21, and by 1899, the UMWA organized its first Arkansas strike. The mine operators, employing a commonly used tactic against strikers, brought in African-American strikebreakers. The UMWA members in Huntington (Sebastian County) decided that none of their strikes could be successful while the miner operators still had these replacement workers, or “scabs,” employed. During a 1904 strike that ended with the terrorizing of black families, white miners in Bonanza (Sebastian County) requested that the mining company remove about forty black miners from the payroll. The mine operators refused, and, after this refusal, about 200 miners drove out the black workers and their families in what has been called the Bonanza Race War. Ironically, both the company and the union claimed to defend the black workers (as some were reportedly even UMWA members) and blamed each other for the violence.

In 1900, mine operators formed the National Civic Federation in order to counteract the massive gains in union membership since the turn of the century. The federation continuously published anti-union propaganda, and, along with other smaller operator-formed organizations, sought to stop to the growth of unions in the United States. Much of their propaganda grew from successful movements like the Great Anthracite Coal strike of 1902 in Pennsylvania, in which the UMWA’s major coal strike caused a nationwide shortage of coal. As winter approached, President Theodore Roosevelt had held a mediation between the operators and representatives of the UMWA for an opportunity to end the strike; the operators refused to reach an accord with the workers until Roosevelt finally threatened both sides with military intervention. The miners returned to work after five months of striking.

On April 6, 1914, in Sebastian County, miners once again rose up against the operators. More than 1,000 people crowded around Mine Number Four of Prairie Creek Mining Company to hear the orations of activist Freda Hogan. The participants were so invigorated by Hogan that they marched to the mining operation in an attempt to “negotiate” with the operators. A battle between the miners and armed guards broke out, with the miners physically besting the guards. Energized by the victory, the miners continued into the mines, where they successfully shut down production and ridded the mines of all non-union workers. The UMWA was forced into a long legal battle with the company, Coronado Mining Company, for damages to the mine. In 1917, a judge ruled in favor of the company, awarding them reparations of $720,000; the UMWA settled out of court for $27,500. The sympathies of the court reflected the trend of dissatisfaction and distrust of unions and further drove a wedge between workers and government. The UMWA soon lost public favor in Arkansas after the Sebastian County action in 1914. It was also found guilty of violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act with a 1915 strike, known as the Wheelbarrow Strike, which was a reaction to the state legislature lowering miner salaries.

By 1917, the national UMWA had a membership of 334,000 miners, by far making it the largest and most powerful union in the United States. After World War I, corporations like the United States Steel Company refused to cooperate with the UMWA, accusing members of Bolshevism. But after World War I, wartime contracts—which included a freeze on wages—ran out, and in 1919, the UMWA requested sixty-percent wage increases, along with a thirty-hour work week. The mine operators refused to comply. In response, the UMWA organized a national strike day on November 1, which resulted in a twenty-seven-percent wage increase for miners.

The UMWA received federal support during the Great Depression. In 1933, with the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (which limited overproduction and allowed for collective bargaining), the union was able to force mine operators to once again accept the “closed shop,” which helped to raise wages and reinvigorate union membership. Arkansas experienced increased active membership, as well as increased union advocacy by organizers.

The UMWA played a major role in shaping the Arkansas workday for all employees within and outside the mining industry, much through federal labor regulations. In 1898, the union achieved a federal standard of the eight-hour work day. In 1946, it won a guarantee for health and retirement benefits for all workers. Then, in 1969, it was able to secure for the nation additional health and safety protections to ensure the longevity of workers.

Throughout its long history, the UMWA—which has nearly 80,000 members—has acted as a major political voice for workers. Arkansas membership is based in UMWA District 12, which runs from Louisiana up the middle of the United States. The UMWA pays out $2 million annually to retirees in Arkansas.

For additional information:

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Lewis, Susanne S. “The Wheelbarrow Strike of 1915: Union Solidarity in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43 (Autumn 1984): 208–221.

Sizer, Samuel A. “‘This is Union Man’s Country’: Sebastian County, 1914.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Winter 1968): 306–329.

Steel, A. A. Coal Mining in Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing Co., 1910. Online at http://archive.org/details/coalmininginark00goog (accessed October 26, 2021).

Van Horn, Carl E., and Herbert A. Schaffner, eds. Work In America: An Encyclopedia of History, Policy, and Society. 2 vols. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2003.

Kayla Griffis

University of Oklahoma

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Labor Movement

Labor Movement UMWA Document

UMWA Document

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.