calsfoundation@cals.org

Sterling Robertson Cockrill (1847–1901)

The chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court from 1884 to 1893, Sterling Robertson Cockrill was only thirty-seven years old when he ascended the bench as the youngest chief justice in the state’s history (a record he still holds). A product of a law school education rather than the old apprenticeship system, Cockrill strongly embraced the codification of legal procedures that the Republican Party had enacted during Reconstruction and thus moved Arkansas more into the nation’s judicial mainstream. Although his tenure on the court was short, his influence was long-lasting.

Sterling Robertson Cockrill was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on September 26, 1847, to Henrietta McDonald Cockrill and her husband, Sterling Robertson Cockrill. Young Cockrill was sometimes identified in Arkansas as “junior” and shared his full name with at least five other kin. His father, a planter with holdings in Tennessee and Alabama, moved to the Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) area in 1855. Young Cockrill was attending school in Nashville at the outbreak of the Civil War. After continuing his education in Georgia, he followed two older brothers into the Confederate army. Wounded at the Battle of Atlanta, he rose to the rank of sergeant.

After the war’s end, Cockrill attended Washington College (whose president, Robert E. Lee, was related to Cockrill’s mother) and then studied law at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee, one of the leading law schools in the South. Armed with a Bachelor of Law degree, he arrived in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1870. In 1872, he married Mary Ashley Freeman, the granddaughter of Episcopal Bishop Andrew Freeman and of former U.S. senator Chester Ashley; they had one daughter and five sons. Not long after arriving in Little Rock, he entered into partnership with Augustus H. Garland, which ended in 1874 when Garland was elected governor.

Cockrill often argued cases before the state Supreme Court and in federal courts. Following the death on September 1, 1884, of Chief Justice Elbert H. English, the Democratic Party convention chose Cockrill as its nominee for the upcoming election, but only on the fifty-ninth ballot. His extreme youth hurt his chances, but as General Robert C. Newton observed, he had “a head as old and as prudent as any in Arkansas.” Cockrill defeated Republican Mason W. Benjamin in the general election and, in 1888, was elected to a full term.

Cockrill’s court consisted of only three justices until the state’s growth led to two more being added in 1888. In his first case, Beard v. State, 43 Ark. 284 (1884), Cockrill crossed swords with the venerable John R. Eakin over the state’s newly enacted law, which made selling any part of a mortgaged crop a felony. Cockrill upheld sending a man to the state penitentiary who had sold less than twenty dollars’ worth to buy medicine for his sick wife. He and Eakin differed also in Maddox v. Neal, 45 Ark. 121 (1885), when Cockrill upheld granting a writ of mandamus to compel a Crawford County school district to open a black school as well as a white one. Eakin argued that there was not enough money to do both, claiming, “The greatest good to the greatest number is all that can be hoped.”

Cockrill’s greatest accomplishment was in enforcing the Republican-adopted code. He wrote many decisions on railroad cases, upholding the fellow servant rule that shielded corporations from lawsuits from injured employees, but also sustaining Arkansas’s version of Lord Campbell’s act that allowed relatives to claim damages from accidents. He upheld the right to vote in Jones v. Glidewell, 53 Ark. 161, 13 S.W. 723 (1890), stating that “it is the province of the courts to see that every legal vote cast is counted.”

Cockrill did receive considerable criticism from his holding in State v. Scales, 47 Ark. 476, 1 S.W. 769 (1886), in which he upheld the state’s Sunday Closing Law that had filled the state’s jails with Seventh-Day Adventists who had been seen working on the first day of the week. His consistent philosophy of upholding legislative enactments and refusing to allow the court to address obvious wrongs did not mean he was oblivious to conditions. He endorsed fellow justice Monti Hines Sandels’s plea for the legislature to fix the probate laws, which allowed administrators to get away with stealing or frittering away estates. But his judicial restraint was such that his court would not even rule in Macowitz v. State, 49 Ark. 170, 4 S.W. 656 (1887), that “a pint of whisky was not a quantity within reason for a youth to have.”

Cockrill resigned his position on April 21, 1893, largely due to the extremely low salary being paid to the justices. He returned to private practice, being joined by his son Ashley, and was involved in a number of high-profile cases, most notably those arising from Attorney General Jeff Davis’s antitrust suits against insurance companies. He was a member of the Omer R. Weaver Camp of the United Confederate Veterans and Beta Theta Pi of Cumberland College, and he was serving as president of the Arkansas Bar Association at the time of his death.

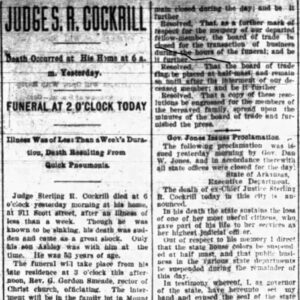

Cockrill died on January 12, 1901. According to press reports, he had been in ill health for several months before being stricken with “la grippe” (influenza) that turned into pneumonia. His death at age fifty-three came as “a great shock” according to the Arkansas Gazette. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Dougan, Michael B. “Sterling Robertson Cockrill: The Youngest Chief Justice, Part 1.” Arkansas Lawyer 46 (Summer 2011): 30.

———. “Sterling Robertson Cockrill: The Youngest Chief Justice, Part 2.” Arkansas Lawyer 46 (Fall 2011): 28.

Hallum, John, Biographical and Pictorial History of Arkansas. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Company, Printers, 1887.

“Judge S. R. Cockrill.” Arkansas Gazette, January 13, 1901, p. 3.

Rose, U. M. “In Memoriam: Sterling Robertson Cockrill.” Arkansas Reports 68 (1901): 613–620.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Mary Cockrill

Mary Cockrill  Sterling R. Cockrill Article

Sterling R. Cockrill Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.