calsfoundation@cals.org

Elizabeth Ann Eckford (1941–)

Elizabeth Ann Eckford made history as a member of the Little Rock Nine, the nine African American students who desegregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. The image of fifteen-year-old Eckford, walking alone through a screaming mob in front of Central High School, propelled the crisis into the nation’s living rooms and brought international attention to Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Elizabeth Eckford was born on October 4, 1941, to Oscar and Birdie Eckford, and is one of six children. Her father worked nights as a dining car maintenance worker for the Missouri Pacific Railroad’s Little Rock station. Her mother taught at the segregated state school for blind and deaf children, instructing them in how to wash and iron for themselves.

On September 4, 1957, Eckford arrived at Central High School alone. The Little Rock Nine were supposed to go together, but their meeting place was changed the previous night. The Eckford family had no phone, and so Daisy Bates intended to go to their place early the next day but never made it. As a result, Eckford was alone when she got off the bus a block from the school and tried to enter the campus twice, only to be turned away both times by Arkansas National Guard troops, there under orders from Governor Orval Faubus. She then confronted an angry mob of people—men, women, and teenagers—opposing integration, chanting, “Two, four, six, eight, we ain’t gonna integrate.” Eckford made her way through the mob and sat on a bus bench at the end of the block. She was eventually able to board a city bus, and went to her mother’s workplace.

Because all of the city’s high schools were closed the following year, Eckford did not graduate from Central High School, but she had taken correspondence and night courses and so had enough credits. She was accepted by Knox College in Illinois but soon returned to Little Rock to be closer to her parents. She also attended Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, and has a BA in history.

Eckford served in the U.S. Army for five years, serving for her first two as a pay clerk and then, upon reenlisting, worked as an information specialist and wrote for the Fort McClellan, Alabama, and the Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, newspapers. Eckford has held various jobs throughout her life. She has been a waitress, history teacher, welfare worker, unemployment and employment interviewer, and a military reporter. She currently works as a probation officer in Little Rock.

Eckford was awarded the prestigious Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as were the rest of the Little Rock Nine and Daisy Bates, in 1958. In 1997, Elizabeth Eckford shared the Father Joseph Biltz Award (presented by the National Conference for Community and Justice) with Hazel Bryan Massery, a segregationist classmate who appears in the famous Will Counts photograph, and during the reconciliation rally of 1997, the two former adversaries made speeches together. In 1999, President Bill Clinton presented the nation’s highest civilian award, the Congressional Gold Medal, to the members of the Little Rock Nine. She is currently a probation officer in Little Rock and is the mother of two sons.

In 2018, Eckford released a book for young readers, The Worst First Day: Bullied while Desegregating Central High, co-authored with Dr. Eurydice Stanley and Grace Stanley and featuring artwork by Rachel Gibson. Later that year, the Elizabeth Eckford Commemorative Bench was dedicated at the corner of Park and 16th streets, and she received the Community Truth Teller Award from the Arkansas Community Institute. In 2024, she was honored as a Living Legend by the Military Women’s Memorial based in Arlington, Virginia.

For additional information:

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Desegregate Little Rock’s Central High School. New York: Washington Square Books, 1994.

Eckford, Elizabeth. “Interview with Elizabeth Eckford.” September 4, 2002. Audio from Grif Stockley Papers, BC.MSS.01.01, Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Bobby L. Roberts Library of Arkansas History & Art, Central Arkansas Library System: Elizabeth Eckford Interview (accessed July 11, 2023).

Jacoway, Elizabeth, and C. Fred Williams, eds. Understanding the Little Rock Crisis: An Exercise in Remembrance and Reconciliation. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Kwasnik, Brianna. “Marching On.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 5, 2021, pp. 1E, 4E. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/sep/05/marching-on/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site Visitor Center. Little Rock, Arkansas. http://www.nps.gov/chsc/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Ly, My. “Eckford of LR Nine Honored for Service.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 24, 2024, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/mar/23/little-rock-nines-eckford-honored-for-her/ (accessed March 25, 2024).

Margolick, David. Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock. New Haven, NJ: Yale University Press, 2011.

———. “Through a Lens, Darkly.” Vanity Fair. http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2007/09/littlerock200709 (accessed July 11, 2023).

Roy, Beth. Bitters in the Honey: Tales of Hope and Disappointment across Divides of Race and Time. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Stanley, Eurydice. “Radiating from Within.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 13, 2022, pp. 1E, 4E. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/nov/13/radiating-from-within/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

National Park Service

Central High School National Historic Site

Eckford Bench

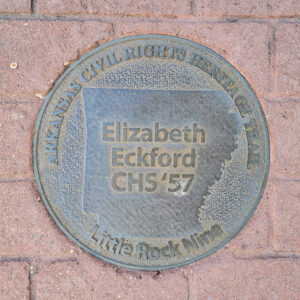

Eckford Bench  Eckford Marker

Eckford Marker  Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High

Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High  Elizabeth Eckford

Elizabeth Eckford  Elizabeth Eckford

Elizabeth Eckford  Little Rock Nine Way

Little Rock Nine Way  Grace Lorch and Elizabeth Eckford

Grace Lorch and Elizabeth Eckford  Thurgood Marshall and Central High Students

Thurgood Marshall and Central High Students

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.