calsfoundation@cals.org

Capital Citizens' Council (CCC)

The Capital Citizens’ Council (CCC) was one of many similar organizations established throughout the South to resist implementation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s May 1954 decision that school segregation was contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment. Formed in 1956 from a Little Rock (Pulaski County) affiliate of the like-minded Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) group, White America Incorporated, to oppose School Superintendent Virgil Blossom’s plan for the gradual integration of Little Rock’s schools, the CCC was the most important segregationist organization during the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School.

The CCC combined traditional racist rhetoric about miscegenation and states’ rights diatribes with allegations of integrationist bias against working-class people. It claimed that there was an alliance between the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the forces of international communism to undermine the Southern way of life. The council harassed the school board, lobbied public officials (particularly Governor Orval Faubus), and organized rallies widely acknowledged to have polarized the community at large. The council supported the school closing referendum of September 1958, the Little Rock Private School Corporation, the purging of unsympathetic teachers, and the Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools in May 1959. The council sponsored both the Mothers’ League of Central High School and the Freedom Fund established to assist those “unjustly” arrested during the disturbances of September 1957. It attacked the reputations of opponents like Daisy Bates, state president of the NAACP, by publicizing her state police file. It also organized a boycott of the Arkansas Gazette because of its “slanted stories [and] editorials”.

Although the council formally disavowed violence in favor of petitions, propaganda, and political pressure, men and women of the council were urged to join the crowds around Central in September 1957 and were disproportionately represented among participants specifically named by the press and bystanders.

While the council was disruptive and frightening, it was not as widely favored as its noisy and inflammatory campaigns suggested. Council-endorsed candidates for school board and municipal office polled strongly but never enjoyed sweeping success at the ballot box. Nor, unlike most other councils, did the Capital Citizens’ Council attract the support of its city’s civic elite.

The council had a membership of 514 in October 1957. Almost three-quarters of the council’s members lived in Little Rock or North Little Rock (Pulaski County), while the majority of the remainder lived in communities like Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke Counties) and Jacksonville (Pulaski County) near the capital or in Delta towns, such as Parkdale (Ashley County) and England (Lonoke County), that were also centers of the state’s African-American population. Around three-fifths of the council’s Little Rock dues-paying supporters were skilled and semi-skilled employees, particularly in sales and ancillary services like banking, insurance, and maintenance, while the rest (including the majority of its leaders) were predominantly the owners of small- to medium-sized family businesses or independent professionals. For example, the council’s chief spokesman was Little Rock attorney Amis Guthridge, and the first three presidents were Little Rock television executive Robert Brown, Broadmoor Baptist Church pastor Wesley Pruden, and Little Rock osteopath Malcom Taylor; the council’s chaplain was L. D. Foreman, president of the Little Rock Missionary Baptist seminary. Very few councilmen were unequivocally lower class. Just over one-fifth of the total council membership was female. Only ten council members actually had children at Central.

Unable to prevent the reopening of Central High after its 1958–59 closure, and with its pretensions to non-violence discredited by a director’s conviction for masterminding a series of bomb blasts in September 1959, the CCC’s influence quickly faded, although a rump group remained vocal until at least 1962.

For additional information:

Bartley, Numan. “Looking Back at Little Rock.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Summer 1966):101–116.

———. The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South during the 1950s. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Cope, Graeme. “‘Honest White People of the Middle and Lower Classes’? A Profile of the Capital Citizens’ Council during the Little Rock Crisis of 1957.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 61 (Spring 2002): 34–58.

Daniel, Pete. Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

McMillen, Neil. The Citizens’ Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971.

———. “White Citizens’ Council and Organized Resistance to School Desegregation in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 95–122.

Graeme Cope

Melbourne, Australia

Capital Citizens' Council Graphic

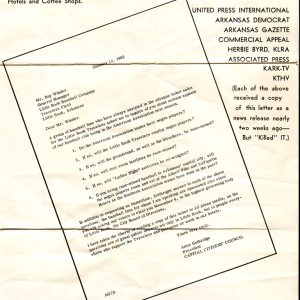

Capital Citizens' Council Graphic  Capital Citizens' Council Anti-integration Flyer

Capital Citizens' Council Anti-integration Flyer  Capital Citizens' Council Graphic

Capital Citizens' Council Graphic  Capital Citizens' Council Meeting

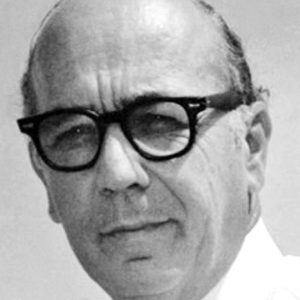

Capital Citizens' Council Meeting  Wesley Pruden

Wesley Pruden  Segregationist Rally

Segregationist Rally

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.