calsfoundation@cals.org

Bullfrog Valley Gang

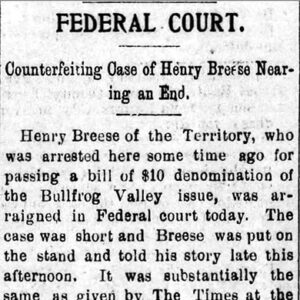

The Bullfrog Valley Gang was a notorious counterfeiting ring that operated in the wilderness of Pope County during the depression of the 1890s. The gang’s origin and methods were mysterious, but the New York Times reported its demise on June 28, 1897. The article said deputy U.S. marshals attached to the federal district court at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) had captured three men, effectively breaking up “the once-famous band of counterfeiters known to secret service operators all over the United States as the Bullfrog Valley Gang.” Previous arrests were reported in Arkansas earlier in the year. In all, some fifteen men were arrested and convicted in federal courts at Fort Smith and Little Rock (Pulaski County). Others, in Arkansas and other states, were convicted of passing the bogus money. A young doctor and his friend in the remote mountain town of Timbo (Stone County) were convicted of smuggling and passing the gang’s bills.

Counterfeiting was an endemic problem in the South after the Civil War, particularly during the steep depression that followed the Panic of 1893. The South did not enjoy the benefits of the national banking system, and currency was in short supply. The wilds of Arkansas were home to a number of counterfeiting operations, some in caves in the Ouachita Mountains and in the wilderness of southwest Arkansas. None, however, received the notoriety of the Bullfrog Valley Gang.

If the Secret Service’s accounts are to be believed, the head of the Bullfrog Valley Gang was George Rozelle, who moved from Nebraska to Pope County in 1893 and, within a couple of years, had printing equipment shipped by rail from Chicago, Illinois. He took the machine into Bullfrog Valley, a remote and inhospitable glen north of Russellville (Pope County) that was famous as a hideout for highwaymen, bandits, and moonshiners. The remote valley, which follows Big Piney Creek from Long Pool to Booger Hollow, was named for Chief Bullfrog, a Cherokee who, according to legend, settled there after his tribe’s forced removal from Georgia (the Trail of Tears) by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. There, Rozelle set up a mint where he and associates made bogus five- and ten-dollar bank notes.

The June 28, 1897, article in the New York Times, along with similar ones that week in the Arkansas Gazette and a number of other newspapers around the state and country, reported that the Bullfrog Valley ring had agents in many large cities around the country and in Toronto, Canada, and Mexico City, Mexico. The spurious money had baffled the government until the Secret Service bureau in Chicago followed a lead on a shipment of supplies to Pope County and tracked the fake money’s source to the infamous Bullfrog Valley. (Four years earlier, the New York Times had carried a story about the ambush by moonshiners of six deputy U.S. marshals in Bullfrog Valley. Two marshals were killed, two were wounded, and two were missing and presumed to have been kidnapped.)

The Mountain Wave, a newspaper at Marshall (Searcy County), commented on the counterfeiting arrests this way: “Everyone knows where the Bull Frog Valley is. The name of Pope County cannot be spoken without recalling to memory this famous valley. That is where the genuine wild-catter [moonshiner] blooms and flourishes as prolific as morning glories on the back porch of a farm house.” Three weeks after the Bullfrog Valley arrests, national newspapers ran stories about a marshal’s arrest of “the noted and desperate female outlaw Rhoda Fuller” at Batesville (Independence County) for passing counterfeit currency, although the stories did not link her with the Bullfrog gang but with another in the mountains of Independence County.

An article in the Gazette said the Bullfrog counterfeiters had dodged federal agents operating out of the federal courts at Fort Smith and Little Rock by ducking back and forth across the Pope-Johnson county line and evading jurisdiction, but some fifteen men had been arrested by August 1897. Rozelle, who was never mentioned in articles at the time, managed to escape with his printing press.

A later lengthy article in the New York Times on May 12, 1901, which recounted the tireless work of the Secret Service in tracking down thugs, finally explained what happened to Rozelle, although the bureau may have embellished the truth in praising the steadfastness and cunning of its men. It reported that the Secret Service learned that Rozelle (it spelled his name Roselle) had fled Bullfrog Valley and had buried the equipment. An agent found three men who had provided Rozelle with money and assistance. He discovered the general area where the machine was buried, and he moved there and waited two years. One of the three men weakened under the pressure and was about to turn in the other two when he was slain by a load of buckshot fired through his front window, according to the Secret Service. Feeling safe then, one of the men dug up the equipment one night, and the agent arrested him.

The man gave the agent a tip on Rozelle’s location in southern Missouri, but Rozelle had by then moved to Goff Cove in Cleburne County, Arkansas, and had started to farm under another name. Several weeks before the agent arrived at Goff Cove, Rozelle got sick and died. The agent found only his grave.

For additional information:

“How Secret Service Men Track Criminals.” New York Times, May 12, 1901, p. 26.

Johnston, James J. Shootin’s, Obituaries, Politics, Emigratin’, Socializin’, Commercializin’, and the Press: News Items from and about Searcy County, Arkansas, 1866–1901.Fayetteville, AR: Searcy County Publications, 1991.

Mihm, Stephen. A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Folklore and Folklife

Folklore and Folklife Law

Law Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Counterfeiting Article

Counterfeiting Article

My dad and grandpa are from Bullfrog Valley.