calsfoundation@cals.org

Canfield Race War of 1896

On Saturday, December 12, 1896, African-American workers at the Canfield Lumber Company in the small lumber town of Canfield (Lafayette County) were fired on by a mob of whites and forced to leave the area. This was part of a widespread pattern of intimidation of Black laborers in southern Arkansas in the 1890s, a practice that seems to have reached a peak in 1896. There were incidents involving railroad workers in Polk County in August and on the Cotton Belt Railway line in Ouachita County in early December. Later in December, there was a similar incident at a sawmill in McNeil (Columbia County).

These incidents were part of a larger pattern evident in southern Arkansas throughout the 1890s in which white tenant farmers, timber workers, and railroad workers banded together to drive out Black laborers, who were paid less and thus were more attractive to employers. Sometimes this was done by whitecappers or nightriders, who threatened African Americans, hoping to drive them off. When threats failed to work, whites sometimes resorted to outright violence, including lynchings, whippings, and shootings.

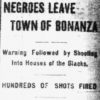

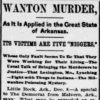

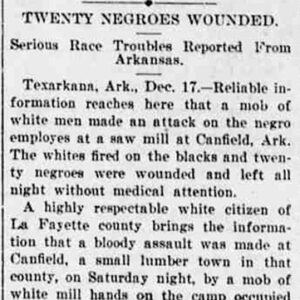

National coverage of the Canfield incident appeared in the Kansas City Daily Journal (Missouri) and the Wichita Daily Eagle on December 18. According to these accounts, which were virtually identical, a “highly respectable white citizen of Lafayette County” had reported that white workers at the Canfield lumber mill had warned the Black workers that they “must leave the mill or suffer the consequences.” The Black workers paid no attention to the warnings and returned to their nearby shanties after work. That night, a mob of white workers surrounded their dwellings and began to fire shots into the buildings. The Black workers ran into the woods, pursued by yet another volley of shots. Twelve of them were wounded, some apparently critically. Two days later, the Daily Huronite (Huron, South Dakota) noted that, after the mob dispersed, “the wounded negroes were left without medical attendance until morning. Those of the negroes who escaped have left the vicinity.”

Both the Journal and the Eagle reported that a similar incident had occurred in nearby Frostville (Lafayette County) on Sunday night, where nine Black workers were shot by birdshot and badly wounded. Both newspapers asserted that the only reason for the shootings “is the determination on the part of the whites to run the negroes out of the county and prevent them from working around the mills.”

On December 27, in a report dated the day before, the Record-Union (Sacramento, California) noted that violence had broken out once again when the Black and white workers in Canfield “filled up with whiskey…and went in search of each other’s gore.” Several workers were seriously wounded, and the sheriff was supposedly on his way to investigate.

For additional information:

“Negroes Attacked by Whites.” Kansas CityDaily Journal, December 18, 1896, p. 2.

“Colored Mill Hands Shot.” Wichita Daily Eagle, December 18, 1896, p. 2.

Matkin-Rawn, Story L. “‘We Fight for the Rights of Our Race’: Black Arkansans in the Era of Jim Crow.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2009.

“Negroes Shot Down.” Daily Huronite (Huron, South Dakota), December 19, 1896, p. 1.

“Race War in Arkansas.” TheRecord-Union (Sacramento, California), December 27, 1896, p. 6.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Presbyterian College

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Labor Movement

Labor Movement Polk County Race War of 1896

Polk County Race War of 1896 Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Race Riots

Race Riots Southern Arkansas Race Riots of Late 1896

Southern Arkansas Race Riots of Late 1896 Canfield Race War Article

Canfield Race War Article

My grandfather, Henry Fort, was fired upon. He was in a wagon with a white man. They were contractors to cut crossties for the railroad. The white man stopped the wagon and ordered my grandfather down. He got off the wagon. The man asked him, NIGGER CAN YOU DANCE? Pappa replied, yes sir. He shot in the ground by Pappa’s feet. Pappa DANCED like he never did before. He didn’t return to work.

I had no knowledge of such things happening in Canfield, Arkansas, of all places. I lived there with my grandparents most of my life but never knew of this.