calsfoundation@cals.org

Hodges v. United States

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906) is a U.S. Supreme Court case resulting in the overturning of the convictions of three white men convicted in 1903 of conspiring to prevent a group of African-American workers from holding jobs in a lumber mill in Whitehall (Poinsett County), a small town in northeastern Arkansas. It was overruled by another Supreme Court decision in 1968, but the decision in Hodges represented an important step in the evolving judicial interpretation of the constitutional amendments passed in the aftermath of the Civil War. The Court’s decision imposed a strict limitation on the application of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime), as well as the ability of the federal government to protect citizens against threats to their civil rights.

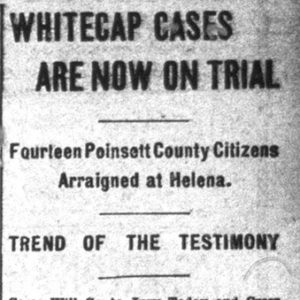

Hodges originated as a local matter stemming from reports of “whitecapping,” a practice not uncommon in the post-Reconstruction South and usually including acts of violence by whites against Blacks. It occurred often enough to have garnered legal notice and gained a definition that focused more broadly on the use of intimidation aimed at forcing people to abandon their home or work. In fact, in this particular case, as with others at that time, the motivation for the incident appeared to be less about race than about class, as the assailants—lower-class whites unable to compete with the Blacks for the limited work available in that economically poor part of the state—sought to drive the competition away. The case gained heightened importance when William G. Whipple, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas, determined that the incident represented an opportunity to send a larger message and contacted the U.S. attorney general, asking for funds to support the use of a special prosecutor for the case. Attorney General Philander Knox responded quickly, praising Whipple’s responsiveness to the problem and approving both the funding and the appointment of Whipple’s choice as prosecutor.

With Department of Justice backing in hand, a full-scale investigation was launched, and two sets of indictments were soon returned. The first case, United States v. Morris, charged that eleven whites had intimidated a group of sharecroppers, while in the other, originally titled United States v. Maples, the government charged that on August 17, 1903, fifteen men had descended upon a sawmill in Whitehall (Poinsett County) and proceeded to intimidate a group of Black workers in an effort to get them to abandon their jobs. Before either set of defendants were brought to trial, their attorneys filed demurrers (motions seeking dismissal of the indictments), arguing that the statutes under which the indictments had been brought—sections 1977 and 5508 of the Revised Statutes—were unconstitutional, representing an infringement upon the rights of both the states and the individual defendants. These motions were dismissed in an opinion by federal district court judge Jacob Trieber, a German immigrant and the first Jew to be named to a federal judgeship.

From the outset, the central question involved the scope of the Thirteenth Amendment, for all acknowledged that the action in question had been committed by private citizens, not a government entity. In denying the demurrers, Trieber ruled that the amendment marked “a great extension of the powers of the national government,” one that allowed the government to protect the freedom of individuals to contract for their labor, which is a central part of the freedom granted by the amendment and which would be guaranteed by prosecuting those who would interfere with that freedom. Too, he asserted that the protection of that right could not be left to the states, under whose authority the now prohibited practice of slavery had operated.

Following Trieber’s ruling, the cases went to trial. In that venue, the basic outlines of the legal, cultural, and philosophical ideas driving the prosecutions became clear. Indeed, while the prosecution argued forcefully that the harassment of the victims had been race related, evidence suggests that, reflective of the class divide typical at the time, the case was more likely pursued at the behest of the town’s prominent whites who viewed whitecapping as something that ran counter to their economic interests. Thus, the real goal of those behind the prosecution was to gain federal support in their battle against a lower class of whites. However, given the identity of the victims, as well as the government’s argument, the case became a test of how far the government would and could go to protect the rights guaranteed by the Reconstruction amendments.

In the Morris case, the government was unable to secure any convictions, as the defendants maintained a united front that left the government unable to present any direct testimony of the alleged intimidation. However, in the Maples case, three of the defendants charged with conspiring to intimidate the mill workers were convicted. Those three defendants quickly appealed their convictions, and in March 1904, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

As the case, now labeled Hodges v. United States, headed to the U.S. Supreme Court, the fundamental issue to be addressed was the right of African Americans to contract for their labor, but no less important was the question of whether the Thirteenth Amendment made the right guaranteed by the Constitution or federal laws and thus subject to protection by the federal government, rather than the states. Another question facing the Court centered on the reach of the Thirteenth Amendment. It had to determine whether the amendment was intended only to secure the freedom of the enslaved African Americans, or whether the prohibition against slavery and the protections central to that edict applied to all people. This was a question of no small relevance at a time when reports of abuses against Italian immigrants and Chinese laborers were commonplace. Ultimately, the Supreme Court had to confront the question of the Thirteenth Amendment’s intent as well as the question of whether the federal government had the power to protect the newly granted rights.

Confronted by this array of issues, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision that influenced civil rights and race relations for almost half a century. The Court’s 7–2 ruling, authored by Justice David Brewer, threw out the convictions of the three men—Reuben Hodges, William Clampit, and Wash McKinney—but more significantly, it imposed substantial limitations on both the reach of the Thirteenth Amendment and the federal government’s power to enforce the amendment and protect the rights it guaranteed. Central to the Court’s ruling was the distinction between the imposition of slavery—something clearly prohibited by the Thirteenth Amendment—and the denial of freedom, in this case the freedom to contract for work, that was less clearly expressed in the amendment. Such an inquiry required the Court to interpret the definition of slavery. While relying more on the common usage of the word “enslavement,” the Court acknowledged that a central component of slavery, as previously practiced, was the act of rendering an individual unable to make or perform a work contract, and while the government argued that the defendants had done just that, the Court majority found that not “every wrong done to an individual by another…operates…to abridge some of the freedom to which the individual is entitled.” The Court ruled that while an individual is entitled to have his property safe and to be safe from assault, no personal violation of those rights can be said to “reduce the individual to a condition of slavery.” Beyond that, the Court ruled that the protection of these rights was the responsibility of the states, not the federal government.

Too, considering whether the Thirteenth Amendment served to protect only the rights of the African Americans, the Court declared that the Thirteenth Amendment was not intended to “denounce every action done to an individual which was wrong if done by a free man and yet justified in a case of slavery and to give to Congress the authority enforcing such denunciation.” Rather, in conjunction with the post–Civil War Fourteenth Amendment (which defines citizenship and contains clauses relating to privileges and immunities, due process, and equal protection) and the Fifteenth Amendment (which prohibits the denial of suffrage based on race or previous condition of servitude), the Thirteenth Amendment aimed to give the African Americans full citizenship, so that their interests would be best served by “taking their chances with other citizens in the states where they should make their homes.”

In a typically forceful dissent, one three times as long as the Court’s opinion, Justice John Marshall Harlan argued that the Thirteenth Amendment authorized the federal government to protect the rights not only of those who had been freed by the end of slavery but also of any citizen whose freedom was threatened. Harlan, joined by Justice William R. Day, also argued for a significantly more expansive view of federal power, echoing Trieber’s belief that only the federal government could adequately protect the rights secured by the Thirteenth Amendment.

The case was important for many reasons, as it represented the next and, in some ways, final step in the development of both the Court’s understanding of the role the Reconstruction amendments would play in the lives of the nation’s now free Black citizens, as well as the role of the federal government in enforcing those evolving rights. Not until after World War II, in response to a concerted legal campaign by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), would the Supreme Court reexamine its previous rulings, ultimately endorsing expanded applications of the amendments in question and the federal government’s power to enforce their guarantees. Only then, in a footnote in the 1968 decision in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., was Hodges v. United States overruled.

For additional information:

Aucoin, Brent J. A Rift in the Clouds: Race and the Southern Federal Judiciary, 1900–1910. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1. Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center. http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/203/1/case.html (accessed February 8, 2024).

Klarman, Michael J. From Jim Crow to Civil Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Mahoney, Martha R. “What’s Left of Solidarity? Reflections on Law, Race, and Labor History.” Buffalo Law Review 57.5 (2009):1515–1596. Online at http://www.buffalolaw.org/past_issues/57_5/Mahoney%20Web%2057_5.pdf (accessed February 8, 2024).

Pruden, William H. III. “Black Workers, White Nightriders, and the Supreme Court’s Changing View of the Thirteenth Amendment.” In Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre, edited by Michael Pierce and Calvin White. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Jacob Trieber

Jacob Trieber  Whitecap Article

Whitecap Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.