calsfoundation@cals.org

White River Expedition (January 13–19, 1863)

| Location: | Prairie County |

| Campaign: | White River Expedition (January 13–19, 1863) |

| Date: | January 13–19, 1863 |

| Principal Commanders: | Brigadier General Willis A. Gorman (US); Not reported (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Gunboats USS St. Louis, USS Romeo, USS Forest Rose, Twenty-fourth Indiana Infantry (US); Not reported (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | None (US); 95 to 150 prisoners (CS) |

| Results: | Union victory |

Conducted in support of early operations against Vicksburg, Mississippi, this expedition helped Federal forces maintain control of the strategically valuable Memphis and Little Rock Railroad between DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Shortly after the capture of Arkansas Post in January 1863 by Major General John A. McClernand, Brigadier General Willis A. Gorman—commander of the District of Eastern Arkansas—moved his command from St. Charles (Arkansas County) toward DeValls Bluff onboard the gunboat USS St. Louis. By a rapid advance on January 17, Gorman surprised two companies of Confederate infantry and forced them to flee, interrupting their attempt to load two large cannon onto a steamboat. An additional assault upon the Confederate rear defeated and captured most of the remaining Rebel force, as well as the town of DeValls Bluff. The spoils of this victory included two eight-inch Columbia siege guns with carriages, ninety Enfield rifles, twenty-five prisoners, and control of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad between DeValls Bluff and Little Rock.

Also on January 17, Gorman sent the Twenty-fourth Indiana Infantry upriver on the gunboats USS Romeo and USS Forest Rose, where it captured the town of Des Arc (Prairie County) and a supply train headed for Little Rock. The spoils captured at Des Arc included the town’s postal and telegraph offices, seventy prisoners, several thousand bushels of corn, and 200 artillery rounds previously taken by Confederates when they captured the steamer Blue Wing No. 2, as well as the destruction of all Confederate ferries operating on the White River up to Des Arc. Afterward, Gorman sent troops to Batesville (Independence County) to capture or burn Blue Wing No. 2.

Gorman also scouted the location, strength, and intent of Confederate commands in or near Little Rock. He estimated Major General Thomas C. Hindman’s command in Little Rock at 25,000, and he reported Brigadier General Henry E. McCulloch encamped at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County); Brigadier General John M. Hawes, however, remained at Hicks’s Railroad Station on the west side of the Arkansas River despite apparent orders to reach Arkansas Post. Based on this intelligence, Gorman considered it unlikely that the Confederates would make a significant fight to retain possession of Little Rock.

Gorman hoped to move his Federal cavalry toward Little Rock via Brownsville (Lonoke County), but recent snow melt turned the Grand Prairie into a small marsh that prevented this movement. This also stymied Confederate efforts to cross the prairie or cut bridges over Bayou Meto. Gorman did manage, however, to send 1,200 cavalry troops from Helena (Phillips County) to Clarendon (Monroe County), where they quickly became isolated by heavy rains and impassable terrain.

Shortly after Gorman’s occupation of Des Arc, McClernand (under authority of Major General Ulysses S. Grant) ordered Gorman to transfer Brigadier General Clinton B. Fisk’s brigade to McClernand’s command at Napoleon (Desha County), in accord with standing orders to prioritize the operations underway against Vicksburg. This transfer essentially forced Gorman’s operation to a halt at Des Arc. Gorman reluctantly complied but expressed concern that the loss of his largest brigade (3,500 men), on top of other recent redeployments from his command, would reduce his strength to less than 5,000 and complicate his ability to hold Clarendon, possession of which reduced Confederate threats against DeValls Bluff. Despite his earlier assessment of Confederate deployments near Little Rock, Gorman also argued that the transfer would leave his command vulnerable to attack by Confederates positioned in and around Little Rock.

In addition to Gorman’s concerns, Major General Samuel R. Curtis (commander of the Department of Missouri and Gorman’s immediate superior) had hoped to build on Gorman’s initial successes; by uniting Gorman’s force with other Union troops on the eastern side of the White River, along with a few gunboats, Curtis hoped to clear northern Arkansas of all Rebel populations. Curtis further hoped that the Federal line could then be extended and maintained to the Arkansas River. The redeployment of a large portion of Gorman’s command, however, made Curtis fearful of the Federals’ ability to maintain control over the railroad to Little Rock and, in turn, the potential for a renewed Confederate presence north of the Arkansas River that could be used to launch raids into Missouri. Despite these concerns, Fisk’s brigade transferred to McClernand’s command by late January.

Although restricted by the needs of the Vicksburg campaign, the White River expedition proved a modest success, including the capture and occupation of DeValls Bluff and Des Arc, as well as two eight-inch Columbia siege guns with carriages, 200 small arms, hundreds of rounds of artillery ammunition, the destruction of three railroad cars and a depot, several miles of railroad track and two railroad bridges, a telegraph, a large stash of Confederate mail, various stores and equipment, and at least 150 Confederate prisoners.

Contemporary accounts, however, vary somewhat in their assessment of the expedition. Fisk reported that Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter voiced opposition to an expedition to DeValls Bluff but did not specify the reasons for Porter’s objections (Porter likely believed this expedition would divert resources necessary to his impending Yazoo Pass Expedition, which got underway in early February). Fisk characterized Porter’s cooperation as lackluster and seems to blame him for making the venture less productive than anticipated. Gorman and Curtis, however, declared the expedition a complete success.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Huff, Leo E. “The Memphis and Little Rock Railroad during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964). 260–270.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 17, part 1. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1886.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 22, parts 1 and 2. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1888.

Robert Patrick Bender

Eastern New Mexico University–Roswell

St. Charles, Capture of

St. Charles, Capture of Weather in the Civil War

Weather in the Civil War ACWSC Logo

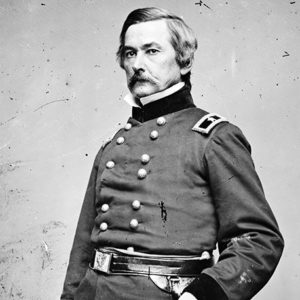

ACWSC Logo  Willis A. Gorman

Willis A. Gorman

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.