calsfoundation@cals.org

Atkins Race War of 1897

What most newspapers described as the “Atkins Race War” occurred in Lee Township of Pope County in late May and early June 1897. In what appears to have been an unprovoked incident, a group of African Americans attacked two white men, Jesse Nickels and J. R. Hodges, just south of Atkins (Pope County) on May 30. In subsequent encounters, several residents of Lee Township, both white and black, were killed and wounded. Despite the fact that the events in Pope County attracted national attention, the extant newspaper records provide little information regarding the motivations of those who perpetrated the violence.

This area of the county, located in rich farmland along the Arkansas River, was populated mostly by farmers. Atkins, which was on the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, had the advantage of two nearby ferries that crossed the river, and it served as a cotton market and trade center for the region. One interesting aspect of these incidents is that African Americans, who were in the minority in Pope County, defended themselves and resisted arrest.

Many parts of Arkansas were not hospitable to African Americans in the late nineteenth century. There were a number of reasons for this. Because black workers had been attracted to the area from other parts of the South and were farming and working in the sawmills for much less pay than white workers received, some whites saw them as a threat to their jobs. In addition, most black citizens at this time were Republicans, while the Democratic Party was the preferred party of the white power structure of both the state and the South as a whole. Political and economic tensions resulted in the widespread use of intimidation, such as whitecapping/nightriding and lynching, in an effort to drive out black residents. The number of incidents in the state during the 1890s was startling: the Hampton Race War of 1892, the Canfield Race War of 1896, the Polk County Race War of 1896, the Nevada County Race War of 1897, and the Little River County Race War of 1899 constitute only a handful of the atrocities visited upon the black population. Persecution tended to be most prevalent in areas where the black population was proportionally the smallest; by the early twentieth century, some towns and even whole counties had become totally white.

The situation in Pope County was fairly typical of the area and the time. The black population in the county was always fairly small, peaking at 8.6% in 1900. Growth was rapid between 1880 and 1900, however, increasing from a population of 909 African Americans in 1880 to 1,865 in 1900. Most of these, more than 700, arrived between 1880 and 1890. The increase slowed after 1900; between 1900 and 1910, the black population increased by only two.

There was racial violence in Pope County even before the large influx of black residents. In 1875, John Hogan was lynched in Dover (Pope County) for an alleged rape attempt on two white girls. The racial animus continued in the 1880s. On January 26, 1885, a group of men rode up to the Alewine farm just north of Atkins and, stopping at a house where several black families lived, told them all to leave that part of Pope County, which was north of the railroad. The families refused to do so, and on February 11, the mob returned and shot up their house. No one was killed or injured. J. P. Strickling and Walter Cole were arrested for being part of the gang, but the case against them was dismissed.

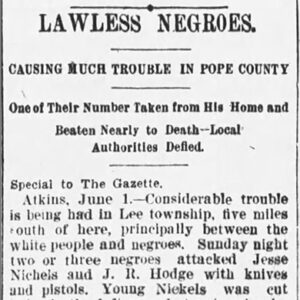

Twelve years later, an incident in Lee Township received national attention. On Sunday, May 30, a “gang of three or four negroes” attacked two white men, Jesse Nickels (Nichols or Nickel in some reports) and J. R. Hodges “with knives and pistols” just south of Atkins. A fight ensued, and Nickels was severely cut. No motive is given for these attacks. Warrants were issued the following day, but the black men insisted that they would not be captured. When a group of white men attempted to take them into custody, two of the white men were injured. That evening (Monday), a mob took one of the black men, William Gaylord, from his home and beat him “into insensibility.” Early reports indicated that he had later died. According to a report in the Salt Lake Herald, by June 2 the list of those killed and wounded included Gaylord, Nickels, an unknown white man who had been fatally shot by black shooters, Reason Edge (a white man “shot by a deputy constable, extent of injuries not known”), and Constable G. W. Edge (“badly cut”).

Other accounts indicate that during the first skirmish, the white combatants attempted to defend themselves with fence rails. The blacks then began shooting, but as soon as one of the whites was shot, they fled. Published reports indicate that tension was high immediately following these events. According to the News (Frederick, Maryland), while officials from Atkins were trying to settle things down, “the negroes are in a very ugly mood and defy arrest. They are being upheld by a few white men, and as they are armed there may be further rioting when the officers attempt to take those for whom warrants have been issued. A correspondent at Atkins says the situation is even more serious than was at first reported.”

During the subsequent arrest attempt, Reason Edge, who was white, helped the blacks to resist arrest, attacking Constable Edge with a knife and severely wounding him. George Edge, a deputy constable, then shot Reason Edge in the arm and arrested him. Since further bloodshed was anticipated, a posse, which included Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Tom D. Brooks, was assembled in Atkins and was headed to the scene of the trouble. A report printed in the Arkansas Gazette on June 4 indicates that things were quieting down in Pope County. Will Gaylord, while in serious condition, was still alive. Some of the participants had appeared before Justice Duke; one African American was fined $50 for carrying a pistol, and Nickels was fined $1 for assault. Two blacks who had been arrested for inciting the riot had been released, and the others had not been apprehended. It is interesting to note that Nickels, one of the supposed victims in the original skirmish, was the only one charged with assault.

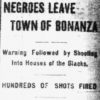

There were no more published reports about the events near Atkins. Trouble was to continue in Pope County during the early twentieth century. In her book A History of the Rushing Community, 1830–1930, Edith Simmons Martin describes a 1903 race war in which “lots of people got murdered,” adding, “It’s pitiful how they murdered the colored and run them off the creek.” In 1910, nightriders posted notices all over Lee Township telling blacks to leave within eight days or they would “proceed to move you ourselves in a very rough way.” The events of 1897, whatever the outcome, can be seen as constituting part of the local tapestry of anti-black violence which, by 1910, was slowing black population growth in the area precipitously.

For additional information:

“The Arkansas Race War.” The News (Frederick, Maryland), June 3, 1897, p. 1.

“A Bloody Race War.” Houston Daily Post, June 2, 1897, p. 1.

“Lawless Negroes.” Arkansas Gazette, June 2, 1897, p. 1.

Matkin-Rawn, Story L. “‘We Fight for the Rights of Our Race’: Black Arkansans in the Era of Jim Crow.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2009.

“Quieting Down.” Arkansas Gazette, June 4, 1897, p. 1.

“Terrible Race War.” Salt Lake Herald, June 2, 1897, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Race Riots

Race Riots Atkins Race War Article

Atkins Race War Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.