calsfoundation@cals.org

Memphis to Little Rock Road

aka: Military Road (Memphis to Little Rock)

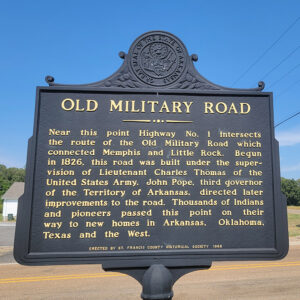

The Memphis to Little Rock Road was one of the first major public works projects in the Arkansas Territory. Spanning the swamplands of eastern Arkansas, the heights of Crowley’s Ridge, and the expanse of the Grand Prairie, it opened the state to emigrants from the east. The road was also a major route for Native Americans during the forced relocations of the 1830s.

The Memphis to Little Rock Road, also known as the Military Road (as were most of the early Arkansas roads constructed under the auspices of the U.S. Army), was authorized on January 31, 1824, when the U.S. Congress passed an act for construction of a road opposite Memphis, Tennessee, through the swamps of eastern Arkansas to the territorial capital of Arkansas at Little Rock (Pulaski County). Surveyors Joseph Paxton and Thomas Mathers and Memphis contractor Anderson B. Carr were hired to lay out a route for the proposed road, though Carr resigned from the team amid disagreement with the others about the best route to follow in crossing the White River.

Lieutenant Frederick L. Griffith was appointed superintendent of the Memphis to Little Rock Road on January 27, 1826, with instructions to make a road “at least twenty four feet wide throughout” with all timber and brush removed and stumps cut as low as possible, marshes and swamps to be “causewayed with poles or split timber,” and ditches four feet wide and three feet deep to be dug on either side of the road.

Griffith advertised for contractors for the first section of the road; he faced criticism that Arkansas citizens were not informed and given an opportunity to bid on the road project. The first section of the road was finished and the second section started by September 14, 1826. Lieutenant Charles Thomas replaced Griffith as superintendent on the project in October 1826.

Despite the failing health of some workers in swampy eastern Arkansas, Thomas reported to Quartermaster General Thomas S. Jesup on January 17, 1827, that contractors were making good progress on the road, though the lieutenant complained bitterly of the Paxton and Mathers report, reporting inaccuracies in both their blazing of the trail and their description of the land through which it passed. “For instance,” Thomas asserted, “they ‘positively aver’ after crossing the Saint Francis ‘that the road will no where be subject to inundation from any river &c’ when they were informed by persons well acquainted with the country & it is also evident from the water marks on the trees, that the county is subject to be overflowed in some places as much as eight feet and by the Mississippi & St. Francis Rivers.” While Blackfish and Shell lakes could be traversed by ferries, Thomas concluded that the areas west of the ridge around Bayou de View and the Cache River were impenetrable and that a new route would be needed to reach the crossing of the White River.

By the end of August, the remaining sections between the White River and Little Rock were completed, and Little Rock and Memphis were connected.

Though it was finished, the road faced harsh conditions, particularly in its eastern reaches, which were subject to severe flooding and were impassable for several months each year. On July 3, 1832, the U.S. Congress appropriated $20,000 for repairs to the road, with Territorial Governor John Pope using the money to improve the road between Little Rock and William Strong’s place near the St. Francis River. Additional congressional funding was sought for the more extensive work needed on the eastern reaches of the road, and Congress appropriated $100,000 and ordered a new survey of the road from Memphis to Strong’s.

Lieutenant Alexander H. Bowman was the third officer to tackle the difficult route through eastern Arkansas, arriving in Memphis in June 1834 with instructions to make contracts for improvements on the road between “a point on the Mississippi River, opposite Memphis, and terminat[ing] at the house of Wm Strong on St. Francis.” Bowman requested—and in late 1835 received—permission to construct an embankment “twenty four feet wide at the top, with suitable slopes, which shall be three feet above highest water” in the first four miles of the road, “creating a continuous levee, from the bank opposite Memphis to the highlands on the South Side of Grandee lake.” After one contractor abandoned the project after three-quarters of his 300-man crew fell ill in the July heat, Bowman hired a second contractor who used oxen and scrapers to create the embankment. Though the initial miles opposite Memphis proved difficult, twenty-three miles of the road were completed by November 1834. After Arkansas became a state on June 15, 1836, Bowman was transferred to other duties as maintenance of the road became a local, as opposed to a federal, concern.

During the years of federal involvement, Congress spent $267,000 of the $660,000 appropriated for territorial Arkansas’s transportation needs on construction of the Memphis to Little Rock Road. The eastern section of the road would continue to suffer the effects of persistent flooding for years to come, with the Arkansas Gazette observing in 1837 that “Emigrants continue to flock to this part of the country but they do so at the risk and cost of passing the most disgraceful bogs, wilderness, and swamps that can be found.”

But construction of the Memphis to Little Rock Road opened an overland route between the Mississippi River and the state capital, the importance of which led the Gazette to observe: “We venture to assert that that there is no one single subject of so much importance to Arkansas as the having of good roads from the interior of the country, to the Mississippi river.” The road also was a major route of Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee), Cherokee, and Chickasaw detachments heading toward the Indian Territory following their forced removal from their homelands in the southeastern United States.

Several surviving segments of the Memphis to Little Rock Road have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places: the Village Creek State Park Segment near Newcastle in Cross County (listed on April 11, 2003), the Henard Cemetery Road Segment at Zent in Monroe County (May 30, 2003), the Brownsville Segment in Lonoke County (September 27, 2003), the Bayou Two Prairie Segment in Lonoke County (September 20, 2006), and the Strong’s Ferry Segment in Cross County (May 15, 2012). The Blackfish Ferry Site in St. Francis County, also associated with the Memphis to Little Rock Road, was listed on the register on April 10, 2003. In addition, the Blackfish Lake to Hill Lake Segment near Gladden and the Highway 306 Segment near Pinetree in St. Francis County were listed on the Arkansas Register of Historic Places on December 5, 2007.

For additional information:

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas 1800–1860, Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

———. “‘Like A Bridge Finished to the Middle of a Stream’: The Memphis Road and Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly (78 (Winter 2019): 339–364.

Brown, Carl E. “Improving the way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed January 2, 2024).

Carter, Clarence E., comp. and ed. Territorial Papers of the United States, Arkansas Territory, 1825–1829. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1954.

Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1972.

Longnecker, Julia Ward. “A Road Divided: From Memphis to Little Rock through the Great Mississippi Swamp.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Autumn 1985): 203–219.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Bayou Two Prairie Segment.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Blackfish Lake to Hill Lake Segment.” Arkansas Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Brownsville Segment.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Henard Cemetery Road Segment.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/National-Register-Listings/PDF/MO0150.nr.pdf (accessed October 19, 2021).

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Highway 306 Segment.” Arkansas Register of Historic Places. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Strong’s Ferry Segment.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

“Memphis to Little Rock Road—Village Creek State Park Segment.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at http://www.arkansaspreservation.com/National-Register-Listings/PDF/CS0039.nr.pdf (accessed October 19, 2021).

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Historic Preservation

Historic Preservation Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Old Military Road

Old Military Road  Village Creek Segment of the Memphis to Little Rock Road

Village Creek Segment of the Memphis to Little Rock Road

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.