calsfoundation@cals.org

Calhoun County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County seat: | Hampton |

| Established: | December 6, 1850 |

| Parent county: | Bradley, Dallas, Ouachita, and Union |

| Population: | 4,739 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 628.60 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

4,103 |

3,853 |

5,671 |

7,267 |

8,539 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

9,894 |

11,807 |

9,752 |

9,636 |

7,132 |

5,991 |

5,573 |

6,079 |

5,826 |

5,744 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5,368 |

4,739 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

3,539 |

74.7% |

| African American |

913 |

19.3% |

| American Indian |

10 |

0.2% |

| Asian |

6 |

0.1% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

9 |

0.2% |

| Some Other Race |

54 |

1.1% |

| Two or More Races |

208 |

4.4% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

127 |

2.7% |

| Population Density |

7.5 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$46,417 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$23,688 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

13.4% |

|

Located in south-central Arkansas, with its southernmost border about twenty-five miles from the Louisiana state line, Calhoun County has the smallest population of Arkansas’s seventy-five counties. Hampton is the only town with more than 1,000 residents. Thornton, Harrell, and Tinsman are the only other incorporated communities. The economic base is timber, sand, and gravel. The majority of the workforce is employed in manufacturing.

Pre-European Exploration

There are about 350 archaeological sites known in Calhoun County, testifying to the habitation of Native Americans in the region for thousands of years. Two prehistoric mounds—Boone’s Mounds and the Keller Site—believed to be from the Coles Creek culture of the Late Woodland Period, are preserved near Calion (Union County) and are on the National Register of Historic Places. There are no historic descriptions of Indian residents in the area, which likely passed from the control of one group to another as different tribes became more or less influential. The last native residents are likely to have been the ancestors of the historic Koroa Indians.

European Exploration and Settlement

Recent studies indicate that the first European explorer of present-day Arkansas, Hernando de Soto, never entered what is now Calhoun County. The legend persists, however, that some of the 700 hogs with his expedition escaped and flourished in the river bottoms there. Whatever their origin, the presence of so many feral hogs gave rise later to the appellation of “Hogskin County.”

French-Canadian hunters, trappers, and traders were probably the first Europeans to visit the area. Because their way of life did not pose a threat to the Indians, the two cultures were usually able to live and work in harmony. These Frenchmen left their lasting mark with such local place names as Acacia (Locust) Bayou, Champagnolle, and Moro.

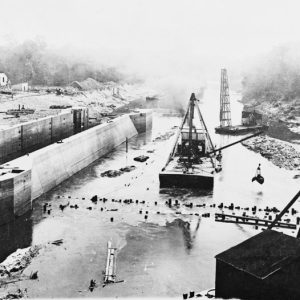

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The Hunter-Dunbar expedition was undertaken by George Hunter and William Dunbar, who were officially the first white American residents to visit what is now Calhoun County. Their exploration of the Red, Black, and Ouachita rivers lasted from October 1804 to January 1805. As they traveled up the part of the Ouachita that borders Calhoun County, they saw their northernmost alligator here, and Hunter reported seeing Indian markings carved and painted on a tree near the water. They were impressed by the variety of trees.

During the early 1800s, policies of Indian Removal in the east caused a stream of Native Americans to pass through the southern part of the Arkansas Territory. Some of these displaced peoples followed their own “Trail of Tears” via a route across present-day Calhoun County to Ecore a Fabri—present-day Camden (Ouachita County)—and eventually to Indian Territory. This route may have followed the old Caddo Trace mentioned by Hunter and Dunbar. The Chicot Trace mail route seems to have followed a similar path.

With the Indians gone, settlers from other states began to arrive. Attracted by the rich bottomland and the easy access for trade provided by the river, many families from Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee chose this area. The Champagnolle land office located in nearby Union County was opened in 1845 to handle the awarding of federal land patents.

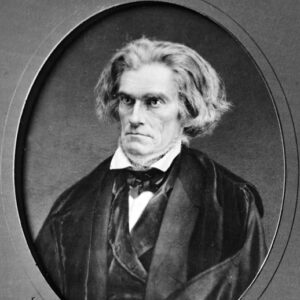

The first settlement in what is now Calhoun County was at Chambersville, which claims the first store, first church, and first post office. In December 1850, in response to a need for a more conveniently located place to conduct official business, parts of Bradley, Dallas, Ouachita, and Union counties were taken to form the county of Calhoun, named for statesman John C. Calhoun. The county seat was named for John R. Hampton, a state senator who had been influential in the creation of the county.

The new county was located in the geographic region known as the Gulf Coastal Plain. Most of the landscape consists of forested low, rolling hills. The western boundary follows the Ouachita River and Two Bayou Creek, while the entire eastern boundary is formed by Moro Bayou. Champagnolle Creek flows down the center from north to south. The soil is sandy loam, and there is much fertile bottomland.

These geographical features lent themselves to the raising of cotton. Many of the early settlers brought their slaves with them. The land was rich, yet cheap. In addition, the waterways, especially the numerous steamboat landings on the Ouachita River, allowed farmers to ship their cotton to markets as far away as New Orleans and to receive goods in exchange. The county’s first decade was one of growth and prosperity.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census placed the white population of Calhoun County at 3,122, with an additional 981 enslaved people. The county was represented by P. H. Echols, who owned three enslaved people, at the Secession Convention; large-scale row agriculture was extremely important to the economy of the county.

When the Civil War came, men volunteered for such local companies as the Yellow Jackets, the Escopets, and the Invincibles. These companies joined a variety of regiments including the Fourth Arkansas Infantry, Sixth Arkansas Infantry, and the Second Arkansas Cavalry Battalion. Not all county residents were in sympathy with the Confederacy; about forty joined Union forces. The Calhoun County Union League actively opposed conscription efforts in the area, which placed them in conflict with Confederate authorities. This led to the imprisonment and eventual execution of several members. Though there were no battles fought in the county, the war had a serious impact. With over 400 soldiers from the county involved in the war, farming, commerce, and immigration almost came to a standstill. When it was over, the male population of the small county had been decimated.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The county did not recover economically until the 1880s when the St. Louis and Southwestern Railroad, better known as the Cotton Belt, passed through the northwestern corner of the county. This allowed for the harvesting of the large stands of virgin timber and for the subsequent development of the lumber industry. Thornton, with two sawmills, became the largest town in the county; the first newspaper, the Thornton Tablet, was founded there in 1886. Two other large mills at Little Bay and Eureka contributed to an estimated annual output of 36 million feet of lumber by the year 1890.

Multiple incidents of racial violence took place in the county in the late nineteenth century, including the lynching of an unknown African American man in 1872. A “race war” took place in the county in 1892 and three years later, brothers Jim and Jack Ware were lynched after being accused as accessories to the murder of a white man.

Early Twentieth Century

A new county courthouse was built in 1909. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it houses complete records from 1850 to the present. In the 1920s, the population reached a peak never to be surpassed. The discovery of oil in the area brought prosperity to some. A few wells are still in operation in the county.

During the Depression of the 1930s, most residents, being farmers, were able to provide food for their families, but, as elsewhere, there was little cash money for other items. Businesses suffered. Some farmers chose to supplement their income by making “moonshine.” The county became noted for the quality of its whiskey.

Some young people helped their families and themselves by participating in work programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the National Youth Administration (NYA). The Hampton Waterworks, now on the National Register, was built by the Public Works Administration (PWA), and an improved road between Hampton and El Dorado (Union County) was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

World War II through the Faubus Era

In the fall of 1944, the U.S. government confiscated over 68,000 acres of land in Calhoun County and neighboring Ouachita County for the construction of the Shumaker Naval Ammunition Depot. A total of 308 families were forced off their land, receiving between $20 and $50 per acre in compensation. Thousands of construction workers were brought in from other places to construct the depot. The facility was used from 1945 until 1957 for the manufacture, testing, and storage of ordnance, especially rockets. After being declared surplus in 1961, the timber land was sold to International Paper Company, and the depot facilities were sold to Brown Engineering Corporation.

Modern Era

Highland Resources, a subsidiary of Brown Engineering, began to develop and operate the former depot area as Highland Industrial Park. The park is primarily used by defense department contractors, including Aerojet Rocketdyne, General Dynamics, and Lockheed Martin. The Brown Foundation donated land and buildings to house Southwest Technical Institute, with the aim of providing a technically trained workforce for the companies that would locate to the area. Now known as Southern Arkansas University Tech (SAU–Tech), the two-year college provides many educational services. It is home to the Arkansas Environmental Academy and the Arkansas Fire Academy. The Arkansas Law Enforcement Training Academy is also located in the vicinity.

Calhoun County has seen a decline in population in recent years, but so have its neighboring counties. The obvious problem is a lack of employment that would attract newcomers and keep young people at home. Most of the educated youth are lured away by more promising careers elsewhere.

Investigations beginning in the 1970s revealed large deposits of lignite in Calhoun County. Though not presently being mined, this resource may be of future significance in the generation of electric power.

Attractions

Moro Bay State Park, at the junction of Calhoun, Bradley, and Union counties, is a popular location for fishing and water sports. The Moro Creek Bottoms Natural Area, shared with Cleveland County, is one of the few intact tracts of virgin hardwoods still existing in Arkansas. The Lost 40 is a privately owned tract of mature forest located in southeastern Calhoun County. Champagnolle Creek has been nominated as one of Arkansas’s Natural and Scenic Rivers. Each year, thousands of hunters descend on the area as one of the best deer-hunting regions of the state. In April, the Hogskin Holidays Festival and Calhoun County Rodeo attract many tourists.

Calhoun County opened a museum located inside the Calhoun County Library in Hampton in 2015. Exhibits include military artifacts and items from everyday life in Calhoun County circa 1850 to the present.

Famous Residents

Calhoun County has been home to a number of famous people. Colter Hamilton Moses was a utilities magnate for whom Lake Hamilton was named. John Roy Steelman served during the administrations of three U.S. presidents and was a top advisor to President Harry Truman. Raymond Henry Bass won a gold medal at the 1932 Olympics and later served in the U.S. Navy during World War II before retiring as a rear admiral. Wood Newton is a country singer who has written many hit songs. Charles B. Pierce has written and produced a number of popular films, while Harry Z. Thomason has produced several successful television series.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Southern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Calhoun County, Arkansas, ArGenWeb Page. http://www.rootsweb.com/~arcalhou/ (accessed September 20, 2022).

Calhoun County Museum. http://calcomuseum.com/ (accessed September 20, 2022).

Strickland, Mary A. Bounds. The Hogskinner. N.p.: n.d.

Carolyn Stratton Cox

Ouachita-Calhoun Genealogical Society

Revised 2022 by David Sesser, Henderson State University

Calhoun County Courthouse

Calhoun County Courthouse  Calhoun County Courthouse

Calhoun County Courthouse  Calhoun County Loggers

Calhoun County Loggers  Calhoun County Map

Calhoun County Map  John Calhoun

John Calhoun  Ham Moses

Ham Moses  Ouachita River

Ouachita River  Southern Arkansas University Tech

Southern Arkansas University Tech

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.