calsfoundation@cals.org

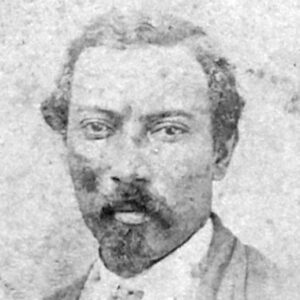

James W. Mason (1841–1874)

aka: James Mason Worthington

James W. Mason of Chicot County was the first documented African-American postmaster in the United States. He later served as a delegate to the 1868 Arkansas constitutional convention and was a state senator.

James W. Mason was born in Chicot County in 1841. His father was Elisha Worthington (1808–1873), the wealthiest landowner and largest slaveholder in Chicot County. Mason’s mother was one of Worthington’s slaves, whose name is unknown. Worthington apparently carried on a longtime, public relationship with this woman. (He did, however, marry Mary Chinn of Kentucky in 1840, but she returned to Kentucky only six months later, claiming that he was an adulterer, and the marriage was annulled.) Mason’s full name, which rarely appears in any public record, may have been James Mason Worthington.

Elisha Worthington recognized both Mason and his sister Martha (b. 1846) as his children. He sent them to the preparatory school at Oberlin College in Ohio. Mason was a student there from 1855 to 1858 and later studied in France. Martha attended Oberlin from 1860 to 1861.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, James and Martha Mason returned to Chicot County, where they oversaw Worthington’s affairs, including his large plantation, Sunnyside, while he resettled in Texas. Worthington returned to Chicot County after the war, but ill health and economic problems caused him to begin selling his landholdings in 1867.

In 1867, James Mason was appointed postmaster at the Sunnyside post office, making him the first documented black postmaster in America. In November 1867, he was elected as a delegate to the Arkansas constitutional convention, which convened in January 1868. He also served in the Arkansas Senate during the 1868–69 term. According to the 1870 census, Mason was a planter who owned real estate worth $10,000 and personal property valued at $2,000.

At some point, Mason married a mulatto woman named Rachel. They had at least one daughter, Fannie Worthington, born around 1867. According to the records of the U.S. State Department, Mason was appointed Resident Minister/Consul General to Liberia on March 29, 1870, but never took up the post.

Mason continued to be active in politics. He served in the state Senate again in 1871–72, while at the same time serving as the probate judge for Chicot County. During this time he was a central figure in the “race war” that erupted in the county during that period. Because he was Chicot County sheriff from 1872 until 1874, the courts tried to hold him accountable for instigating the massacre in Chicot County. In the summer of 1873, Mason was arrested and endured a “long and tedious trial.” He was convicted of murder and sentenced to confinement in the Drew County jail until the next meeting of the circuit court. This apparently did not happen, however, since he was taken to Little Rock (Pulaski County) on a writ of habeas corpus and discharged on October 6. Subsequently, Colonel John A. Williams was appointed a special judge in the case, and a grand jury was selected. According to the Arkansas Gazette, area citizens were hopeful that the grand jury would be able to “ferret out the dark things of the county” and “indict and punish the parties who were guilty of those outrageous murders of two years ago.” However, Williams eventually dismissed the grand jury on a technicality. The Gazette speculated: “It was not a healthful grand jury for Mason and his abettors and hence, in our opinion, it was for that reason discharged.”

Elisha Worthington died without a will in 1873. James and Martha Mason apparently filed a court case in order to receive a portion of his inheritance. They won the case, but it went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and was not settled until four years after Mason died. In 1879, the court ruled that since Worthington had taken Martha to a free state, Ohio, to be educated, their former relationship as master and slave had been dissolved. Even though she had returned to Arkansas, a slave state, she was thereafter a free woman. Thus she was eligible to inherit.

James Mason died of unknown causes in late November 1874. His wife, Rachel, moved to Mississippi, where Fannie pursued her education. Rachel later married John W. Piles and moved with him to St. Louis, Missouri, where Fannie was further educated. They then moved to Washington DC, where Fannie completed her education and was later employed as a teacher in Maryland and New Jersey. Fannie Worthington married missionary Alfred L. Ridgel in 1893.

For additional information:

“Bloody Chicot.” Arkansas Gazette, February 10, 1874, p. 1.

Campbell, James T. Middle Passages: African American Journeys to Africa, 1787–2005. London: Penguin, 2007.

Foner, Eric. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. Rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Gibbs, Mifflin Wistar. Shadow and Light: An Autobiography with Reminiscences of the Last and Present Century. Washington DC: 1902. Online at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28183/28183-h/28183-h.htm (accessed October 28, 2021).

Ridgel, Alfred Lee. Africa and African Methodism. Atlanta: Franklin Printing and Publishing Company, 1896. Online at http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/ridgel/ridgel.html (accessed October 28, 2021).

Whayne, Jeannie M., ed. Shadows over Sunnyside: An Arkansas Plantation in Transition, 1830–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Worthington v. Mason, 101 U.S. 149 (1879). Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center. http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/101/149/case.html (accessed October 28, 2021).

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century)

African American Legislators (Nineteenth Century) Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 James W. Mason

James W. Mason

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.