calsfoundation@cals.org

Cleburne County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Heber Springs |

| Established: | February 20, 1883 |

| Parent Counties: | Independence, Van Buren, White |

| Population: | 24,711 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 553.96 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

7,884 |

9,628 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

11,903 |

12,696 |

11,373 |

13,134 |

11,487 |

9,059 |

10,349 |

16,909 |

19,411 |

24,046 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25,970 |

24,711 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

22,953 |

92.9% |

| African American |

69 |

0.3% |

| American Indian |

133 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

102 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

11 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

232 |

0.9% |

| Two or More Races |

1,211 |

4.9% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

632 |

2.6% |

| Population Density |

44.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$44,483 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$27,227 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

14.0% |

|

Although it was the most recent of Arkansas’s seventy-five counties to be formed, Cleburne County has proved to be a tourist mecca for the state. Thousands of Arkansans and visitors are attracted to Greers Ferry Lake and the Little Red River for fishing, swimming, and other water sports. Even before the lake was formed, summer visitors were attracted to the mineral springs in Spring Park in Heber Springs, the county seat, and to the waterfalls and unique rock formations in the surrounding hills.

Cleburne County has a generally rugged terrain with elevations ranging from 270 feet above sea level in the river bottomland of the southeast part of the county to 1,400 feet in the northwest section. The valleys have some alluvial, fertile land; the mountains have traces of lead, coal, and possibly other minerals. The Little Red River, Greers Ferry Lake, and countless smaller streams and springs furnish an abundant water supply.

Pre-European Exploration

The land that became Cleburne County was first inhabited by Native Americans many thousands of years ago. The first inhabitants lived by hunting and collecting wild plants and other resources. Settlements were usually open air sites near streams, but rock shelters were also used for storage and other short term uses. Many of these sites are now under Greers Ferry Lake.

One of the largest known sites is just below Greers Ferry Dam on the Little Red. A 1958–1959 investigation found several houses, one of which was excavated completely. The village may have been a rural community affiliated with a large center somewhere downstream. By the time of historic records, the Osage were controlling the area, claiming it and using it as a hunting territory to the exclusion of other groups.

European Exploration and Settlement through Early Statehood

One party of Hernando de Soto’s expedition in l541–1542 may have traveled as far northwest as Cleburne County, searching for gold, copper, and other minerals, but it was more than 100 years later, with the expedition of La Salle, before any record is found of white men’s arriving in the region again.

The earliest known Anglo-Americans to settle in what is now Cleburne County were John Benedict and his brothers-in-law, William, Davis, and John Standlee. In l812, they left their home in Platton Rock, Missouri, on the Mississippi River and ended their journey on the Little Red River a few miles below the mouth of Devil’s Fork. They cleared thirty acres and built three small cabins. They sold their holdings on the Little Red in 1821, the first land transaction of record in the county.

Some bands of Cherokee moved voluntarily into what is now Arkansas, beginning in the late 1700s. After the New Madrid Earthquake, most of these emigrants settled along the Arkansas River; they received a reservation from the United States government in 1818. A portion of Cleburne County was part of that reservation. In 1828, the Arkansas Cherokee agreed to give up this reservation in exchange for lands west of Arkansas Territory.

The l840 Census listed sixty families in the area that comprises most of Cleburne County. By midcentury, there were colonies of families who had traveled together from Kentucky or Tennessee. They settled on adjoining farms and made up the county’s first communities. The earliest settlers were hunters and trappers who would build a small cabin and move on when game became scarce. Later pioneers were farmers looking for a place to build a home and raise a crop. Some sections had good soil, but much of the land was shallow and rocky. From the mouth of Devil’s Fork to Miller Mountain and below, the bottomland along the Little Red was rich and tillable. Before the Civil War, William Mills established a large plantation on the Little Red near present-day Edgemont, while William H. Lay, who settled south of Quitman in early 1840, built a hand-powered cotton gin and a gristmill.

Civil War through Reconstruction

At the time of the Civil War, what was to become Cleburne County had fewer than 1,000 residents. Two-thirds of these had migrated from Kentucky, North Carolina, or Tennessee. A total of three post offices operated in the area that became Cleburne County: Quitman, Wolf Bayou, and Kinderhook, which later became known as Edgemont. Only a half-dozen area farms had more than 100 acres of improved land, and only two of those larger farms raised cotton. One in seven families in the area in 1860 held slaves.

Much of the area that became Cleburne County was part of Van Buren County at the time of the Secession Convention. James H. Patterson, a merchant from Griggs Township, represented the county at the convention. Patterson owned two enslaved people at the time of the 1860 federal census.

When the war came, many people joined regiments and fought for the South, while others left the state and fought for the Union in regiments from Missouri. Many did not want to get involved, and some joined a peace society, looking for a way to protect their families from roving bands of jayhawkers, who raided, burned, and killed throughout the area.

The Tenth Arkansas Infantry Regiment was organized at Springfield (Conway County) in July 1861. This is where many volunteers from Van Buren County were mustered into the Confederate army. Company A, known as Quitman Rifles, had ninety-four men, including eight non-commissioned officers. Company G was called Red River Riflemen. The Tenth Arkansas Infantry served east of the Mississippi River throughout its career, seeing action in Tennessee’s Battle of Shiloh and later in Louisiana.

Two skirmishes near Quitman (March 26 and September 2, 1864) are listed in Union army reports, including a detailed report of eight days spent raiding and plundering in the hills north of the Little Red. Bushwhackers and jayhawkers continued roving the country after the war.

When the war ended, Confederate soldiers found their way home the best way they could. Ten years before the war, the county’s population had grown to more than 2,000, but, by 1870, the area had lost population. The county swiftly recuperated, with the population almost doubling, from 2,210 in 1870 to 4,025 in 1880. In these years, Tennessee was still the main feeder state for the area, with North Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia following.

Outside Quitman, which had been settled for forty years, nineteen of every twenty families in the area were farmers. They grew Indian corn, potatoes, peas, and beans, and some grew wheat, rye, and oats. Every household had one or more milk cows, and there were more working oxen than horses or mules. Families raised pigs and sheep, wove cloth from wool yarn, and made candles from beeswax.

Quitman, the county’s oldest town, was incorporated in March 1875. The post office, established in l848, became a center for rural postal delivery. Quitman College, chartered in 1871, had no endowments at the time but was liberally financed by William Wakefield Garner, through whose efforts the college was established. It was later supported by the Methodist Church for several years but closed just before the turn of the century.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In August 1881, Max Frauenthal of Conway (Faulkner County) bought from John T. Jones of Helena (Phillips County) a forty-acre tract, including several mineral springs, in a valley near the Little Red. A few weeks later, Frauenthal organized the Sugar Loaf Springs Land Company and sold shares to ten businessmen. The land company’s purpose was to build a town, Sugar Loaf Springs (later to be known as Heber Springs). Frauenthal was elected president of the land company, and Wesley C. Watkins was secretary. Lots were sold, houses erected, and businesses established, and the town began to grow.

Because travel by horse and wagon to Clinton, the Van Buren County seat, was slow and inconvenient, area residents wanted to establish their own county government. Officers of the land company bonded themselves to pay $6,000 to build a courthouse and a county jail on condition that the county seat be located permanently at Sugar Loaf.

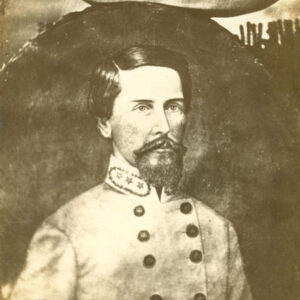

It had been ten years since a county had been formed in Arkansas, but a bill was introduced in the legislature on January 27, 1883, by Senator Zachariah Bradford Jennings of Van Buren County. The bill, which became Act 24 of 1883, passed, and the new county was formed from parts of Independence, Van Buren and White counties, with Sugar Loaf as the county seat. The county was named for General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, who had a brilliant military career in the Confederate army before his death in the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, in 1864. He was memorialized at the request of Cleburne County men who fought under his leadership.

At least one lynching took place in the county, with the killing of William Mercer, a white man accused of rape and murder.

Early Twentieth Century through the Modern Era

In its first quarter-century, Cleburne County lay quietly hidden among the hills, isolated from the rest of the world. In 1908, construction of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA) opened the remote valley to the world. Tourists thronged to the picturesque town of Heber Springs to drink the water from the mineral springs, and doctors from the mosquito-ridden lowlands of southeast Arkansas sent their patients to drink the waters for their curative powers. Tourism thrived.

In 1918, the county was the site of one of three prominent draft wars in Arkansas—armed conflicts between law enforcement officials and deserters from the military or resisters of conscription. In this case, the resisters were Russellites (now known as Jehovah’s Witnesses), whose religious beliefs would not allow them to participate in the war effort. For about a week in July, a posse that grew to about 200 men, along with thirty National Guard members of the Fourth Arkansas Infantry, conducted raids and searches, looking for a band of eight resisters led by Tom Adkisson. Throughout the county, Jehovah’s Witnesses were arrested and rounded up as potential subversives. At the end of the conflict, a posse member had been killed, and the eight men turned themselves in at points outside the county.

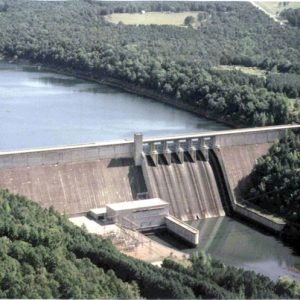

During the Depression, tourism lagged, and the 1940s brought the collapse of the railroad. Cleburne County was isolated again. A soil conservation camp operated by the Civilian Conservation Corps operated near Heber Springs to produce sod to support cattle businesses. As early as the 1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had made preliminary surveys across the Little Red River. Construction of Greers Ferry Dam began in 1959, bringing employment and economic growth. The dam was completed in 1962 at a cost of about $46.5 million. The lake formed by the dam has a surface of 40,500 acres at flood level and a shoreline of 343 miles. President John F. Kennedy made one of his last public dedications when he presided at the dedication of the dam on October 3, 1963.

Cleburne County and Heber Springs formed a joint planning commission in anticipation of the growth expected after the dam and the lake’s formation. Growth was spectacular and spread to the entire county. By one weekend in 1982, the number of weekend visitors to Greers Ferry Lake reached a high of 251,000. The lake and recreational facilities have placed new focus on the area’s natural beauty.

Cleburne County is well known for the musicians and artists who began their careers within its boundaries. Harmonica player and singer Wayne Raney is credited with bringing the harmonica to the masses. Songwriter Melvin Endsley, folksinger Almeda James Riddle, photographer Mike Disfarmer, and musician Teddy DeLano Riedel all originate from Cleburne County. Rimrock Records, a record-manufacturing company, operated in Concord (Cleburne County).

Points of Interest

The Greers Ferry Visitors Center at the west end of the dam north of Heber Springs presents the history of the area and directions to recreational sites. The Cleburne County Historical Society is based in the old post office in Heber Springs on the corner of First and Main. Several structures are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Cleburne County Courthouse, Cleburne County Poor Farm Cemetery, the Dill School, the Quitman Home-Economics Building, the Woman’s Community Club Band Shell, and Old Highway 16 Bridge.

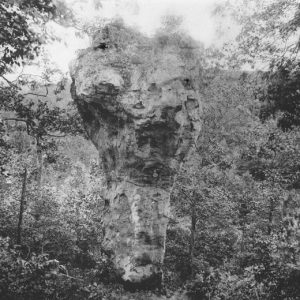

Walking trails in the woods near the lake are near the visitors center and maintained by the park staff. Another point of interest, five miles east of Heber Springs near Highway 110, is Sugar Loaf Mountain, an erosional remnant from which the town of Sugar Loaf (Heber Springs) took its name. The Army Corps of Engineers maintains fourteen public parks with more than 1,200 campsites beside the lake. Several marinas offer boat storage and rental. Commercial docks on the Little Red offer cabins, camping, guide service, and boat rental.

Fairfield Bay, partly located in Van Buren County, and Eden Isle on the lower part of the lake are thriving residential and resort developments offering recreational, sports, and eating establishments. Greers Ferry, the second-largest town in Cleburne County, offers additional recreation activities to visitors.

For additional information:

Barger, Carl J. Cleburne County and Its People. 2 Vols. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2008.

Berry, Evalena. Time and the River: A Centennial History of Cleburne County. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1982.

Cleburne County Historical Society Journal. Heber Springs, AR: Cleburne County Historical Society (1974–).

Evalena Berry

Little Rock, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Black Sulfur Spring

Black Sulfur Spring  Candle Stick Rock

Candle Stick Rock  Cleburne County Courthouse

Cleburne County Courthouse  Cleburne County Courthouse

Cleburne County Courthouse  First Cleburne County Courthouse

First Cleburne County Courthouse  Cleburne County Map

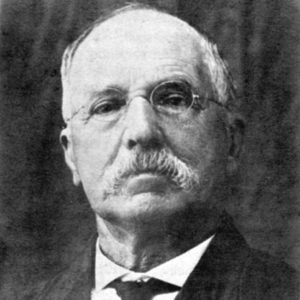

Cleburne County Map  Patrick Cleburne

Patrick Cleburne  Cow Shoals Riverfront Forest Natural Area

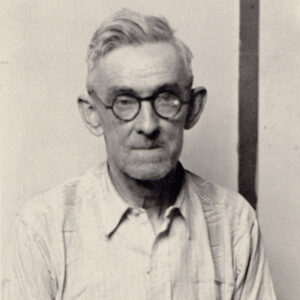

Cow Shoals Riverfront Forest Natural Area  Michael Disfarmer

Michael Disfarmer  Frauenthal House

Frauenthal House  Max Frauenthal

Max Frauenthal  Greers Ferry Dam

Greers Ferry Dam  Greers Ferry Dam

Greers Ferry Dam  Greers Ferry Lake Filling

Greers Ferry Lake Filling  Heber Springs Building

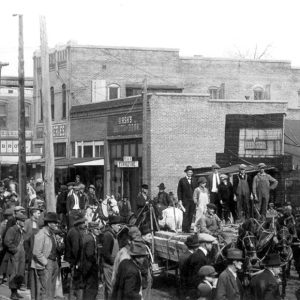

Heber Springs Building  Heber Springs Street Scene

Heber Springs Street Scene  Heber Springs Street Scene

Heber Springs Street Scene  Heber Springs Street Scene

Heber Springs Street Scene  Moonshine Still

Moonshine Still  Narrows Bridge

Narrows Bridge  Ozark Frontier Trail Festival

Ozark Frontier Trail Festival  Quitman Street Scene

Quitman Street Scene  Tumbling Shoals Suspension Bridge

Tumbling Shoals Suspension Bridge  Wilburn General Store

Wilburn General Store  Woodrow Store

Woodrow Store

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.