calsfoundation@cals.org

Cleveland County

| Region: | Southeast |

| County Seat: | Rison |

| Established: | April 17, 1873 |

| Parent Counties: | Bradley, Dallas, Jefferson, Lincoln |

| Population: | 7,550 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 597.91 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

11,362 |

11,620 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

13,481 |

12,260 |

12,744 |

12,570 |

8,956 |

6,944 |

6,605 |

7,868 |

7,781 |

8,571 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,689 |

7,550 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

6,466 |

85.6% |

| African American |

686 |

9.1% |

| American Indian |

35 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

7 |

0.1% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

1 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

87 |

1.2% |

| Two or More Races |

268 |

3.5% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

182 |

2.4% |

| Population Density |

12.6 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$46,684 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$24,225 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.4% |

|

Cleveland County was created on April 17, 1873 as Dorsey County, named after Republican congressman Stephen Dorsey, but the name was changed to honor President Grover Cleveland on March 5, 1885. The Saline River bisects the county from near the northwest corner to near the southeast corner. Moro Creek forms much of the western boundary. When the area was first explored, trees covered a major part of the county. Much of the economy centered on their harvest. The timber industry is still important to the county.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Fossils of sea crustaceans have been found along Salty Branch, as it is known locally, which crosses Arkansas Highway 8 just east of Highway 97. According to an 1818 Quapaw Treaty, the section east of the Saline River in what became Cleveland County was in Quapaw territory, but in the early 1820s, a movement was begun to remove the Native Americans from Arkansas Territory. The third Quapaw Treaty ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1834 was the beginning of the end of their treaty lands in Arkansas. Indians also lived west of the Saline. Arrowheads, celts, and other artifacts have been found, along with a mound at least thirty feet long and eight feet high near the west bank of the Saline River in central Cleveland County.

In 1824, before the last Quapaw Treaty was abrogated, settlers attracted by cheap, fertile land were moving into the area west of the Saline River in Pennington Township, which was then part of Union County (later Bradley County and then Cleveland County). This land soon attracted others to join them. Some of these settlers were planters, who brought their slaves with them to the area, but the majority of farmers owned no slaves. Cotton was the main cash crop originally, but other crops were raised, including large amounts of Indian corn and various food crops.

Civil War through Reconstruction

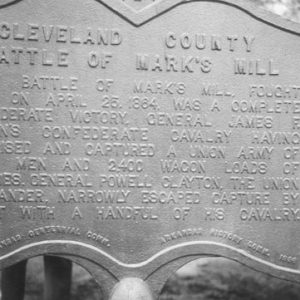

The most important event in what became Cleveland County during the Civil War was the Action at Marks’ Mills on April 25, 1864. Union general Frederick Steele’s forces, which were occupying Camden (Ouachita County) as part of the Camden Expedition, sent 240 wagons escorted by troops commanded by Colonel Francis Drake to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) for supplies. Confederates led by General James Fagan learned the wagon train was expected to cross the Saline River at Mount Elba en route to Pine Bluff and ambushed the Union forces near the Marks settlement. The Confederate attack was successful and led to the capture of the entire wagon train. Union casualties were about 1,500, while Confederate losses were 293; more than 150 freedmen accompanying the Federals were captured, and many were killed . This Union loss caused Steele to withdraw from Camden and return to Little Rock (Pulaski County). Marks’ Mills Battleground State Park has been established at Arkansas Highways 8 and 97. In 1939, a metal marker of the battle was erected, and the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1970.

The Arkansas General Assembly created Dorsey County on April 17, 1873, from portions of Bradley, Dallas, Jefferson, and Lincoln counties. According to the 1880 Census, the first after Cleveland County was formed, the settlers were mainly farmers. By then, the St. Louis and Texas Railroad was being constructed across the county. A major conflict began in the county in March 1889 when fire destroyed the courthouse at Toledo. Rison, Kingsland, and New Edinburg, the county’s other towns, actively sought to be the county seat. After two contested elections, the state Supreme Court decided that Rison would be the county seat on April 11, 1891. The original timber-frame courthouse was replaced by a brick structure in 1911 and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Although the 1880 federal census listed no timber-related businesses or workers, the 1900 census listed more than 350 such employees. Several sawmill settlements grew in area through the 1930s, but farmers continued to outnumber sawmill workers.

At least three lynchings of African Americans took place in the county in the late nineteenth century. Jeff Gardner was lynched on April 18, 1896, for an alleged kidnapping and assault on a white girl, while a man perhaps named Bill Wiley was lynched the following year for allegedly killing a man. Multiple lynchings occurred related to the 1898 murder of Bart Frederick near Kingsland. One of these lynchings took place in Cleveland County when Goode Gray was taken from the Rison jail on July 4, 1898, and hanged from a railroad bridge over the Saline River.

Early Twentieth Century through the Faubus Era

In April 1917, the county began to organize a company of the Arkansas National Guard to be stationed in Rison, but no record of such a unit actually being formed has been found. By early June, 1,070 men aged twenty-one to thirty-one had registered for the draft, and Red Cross committees were being formed. In March 1918, state senator George F. Brown, first lieutenant of the Fourth Arkansas Volunteers, began trying to form a separate county unit to serve in World War I.

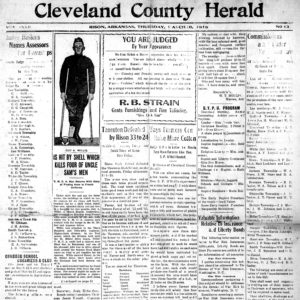

During the Great Depression, the county suffered as many did across the nation, but since most residents were either farmers or had sufficient land to garden nearby, few went hungry. Money was in very short supply, and even the Cleveland County Herald, the only county newspaper, by March 8, 1932, reacted to this shortage by publishing a notice that they would accept “any article of food, poultry, eggs, stove wood, corn, cotton seed or any other item of value” at market value for their newspaper subscriptions. Most of its published editions also gave public notice of people being sued for nonpayment of debts, especially concerning loans on land. Some county residents joined the large migration west looking for jobs and a better way of life.

During World War I and World War II, the county formed boards and organizations to support the war effort and to honor those serving in the military. During World War II, the county bought three peanut pickers and stationed them in different farming areas to help with the nation’s peanuts-for-oil program. Peanuts had long been raised for family use, but wartime needs caused production to increase. Many residents, both male and female, left the county for the military or for defense jobs, and many of these never returned to the county to live.

Modern Era

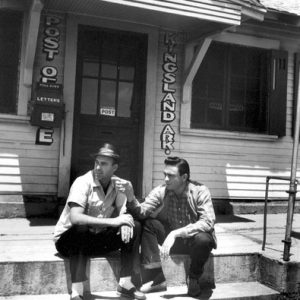

The county observed the bicentennial by inviting its famous native son Johnny Cash, who was born near Kingsland, to return for a concert. On March 20, 1976, he and his wife, June, appeared first at Kingsland, then boarded a Cotton Belt special passenger train for Rison, where he appeared in a parade and performed a free concert at the football field for a crowd estimated at 12,000. On March 31, 1994, Cash returned to Kingsland for the dedication of the new post office named in his honor. Another famous native son was University of Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, also born near Kingsland.

By the late 1970s, the county had at least forty-five hunting clubs, and the number has continued to grow. Numerous hunters from across the state are members of these hunting clubs, and Cleveland County has been among the top ten Arkansas counties in the number of deer killed. In 1988, there were more than forty-five churches, three post offices, and four public schools (Rison, Kingsland, New Edinburg, and Woodlawn) in the county.

After a major fundraising drive and a matching grant from the Roy and Christine Sturgis Foundation in 1992, the county constructed a modern library in Rison. Roy Sturgis and his brother, Pleasant, who were raised near Kingsland, were self-made timber multimillionaires and later philanthropists whose foundations still operate.

The county has no major industry, so many residents travel to nearby counties to work. As in its earlier years, the county has remained a rural area with interests in timber, hunting, and farming. The county has two school districts: Cleveland County, consisting of the former Rison and Kingsland schools, and Woodlawn.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Eagle Press, 1990.

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Cleveland County, Arkansas: Our History and Heritage. Rison, AR: Cleveland County Historical and Genealogical Society, 2006.

Cleveland County Genealogy & History. https://argenweb.net/cleveland/index.html (accessed July 12, 2023).

Lisemby, Doris Mitchell. Taproots in Fertile Soil. Arkadelphia, AR: Autumn Years Ministries, 1993.

Took, Kara D. “‘Yet Will I Leave a Remnant’: Modernization, Out-Migration, and the Rural Churches of Cleveland County, Arkansas, in the 1940s.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Summer 2001): 151–173.

Louise Mitchell

Cleveland County Historical and Genealogical Society

Revised 2022 by David Sesser, Henderson State University

Action at Marks' Mills Marker

Action at Marks' Mills Marker  Calmer Church

Calmer Church  Johnny Cash and Johnny Horton

Johnny Cash and Johnny Horton  Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash  Cleveland County Courthouse

Cleveland County Courthouse  Cleveland County Courthouse

Cleveland County Courthouse  Cleveland County Herald

Cleveland County Herald  Cleveland County Map

Cleveland County Map  Cleveland County Schools

Cleveland County Schools  Grover Cleveland

Grover Cleveland  Stephen Dorsey

Stephen Dorsey  Entering Calmer

Entering Calmer  Lumber Industry

Lumber Industry  Moro Creek Bottoms Natural Area

Moro Creek Bottoms Natural Area

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.