calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock Picric Acid Plant

Arkansans supported the American effort in World War I in many ways. Some served in the armed forces, while others worked to grow and conserve food and make clothing and bandages for the troops. Many worked in a number of war industries, including a munitions plant built outside of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1918, tasked with manufacturing a high explosive—a rapid and destructive chemical explosive—known as picric acid.

Picric acid (trinitrophenol) is made of phenol and several acid compounds that, when combined under proper conditions, form a honey-like substance that can be loaded into artillery shells. It is stable enough to survive the shock of being fired from a cannon, but, when detonated by a fuse, is very destructive. Ten times more damaging than the black powder that preceded it, it is even more powerful than TNT. The British, French, and Americans all used it as their main high explosive on the Western Front. Picric acid is also the basis for the manufacture of chloropicrin, a poisonous gas used in chemical warfare.

When America joined the conflict, it had only one federal facility, the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, producing picric acid. To meet demand, the U.S. government let contracts for two more—one at Little Rock (at a cost of $7,000,000) and a larger one at Brunswick, Georgia.

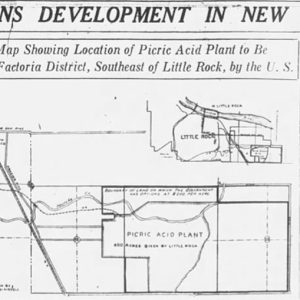

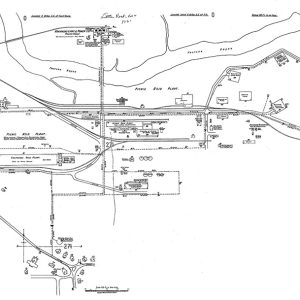

The site selected for the Little Rock Picric Acid Plant was in a new part of the city known as the Factoria Addition. Laid out a few years before the war, the Factoria Addition was home to a handful of timber-related industries. The plans for the plant included new roads and rail lines to Factoria and the installation of water and gas pipelines to fuel the plant.

The plant consisted of four major components: a phenol plant, a building for making nitric acid, another building for sulfuric acid, and a concentrating building. These were surrounded by a large number of storage tanks, administrative buildings, and barracks for construction staff, ordnance workers, and military personnel. These buildings were rushed into production in May 1918. Hundreds of thousands of bricks and board feet of timber were sent to the construction site, and hundreds of carpenters and laborers were hired. The plant opened while still incomplete, and workers and builders labored side by side throughout its operational history.

Though never completed, the Little Rock Picric Acid Plant produced a substantial quantity of munitions during the war. It could have produced more, but staffing the plant was a constant problem. When the contract was let, federal authorities were assured that central Arkansas could provide sufficient hands to work the plant. Within a few months, 2,500 men were working at the plant, and calls went out to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Texarkana (Miller County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), and other cities looking for more workers. People came from outside of Arkansas, as well, to join the war effort. When this number proved insufficient, a work draft in Little Rock, drawing people from trades deemed “non-essential,” was contemplated. Finally, in late 1918, the staffing shortfalls were met by support from the U.S. Employment Service, which looked much farther afield for workers.

In early October 1918, the first of over 1,000 Puerto Rican laborers arrived. They stayed through the rest of the war despite being ill-equipped for winters outside of the Caribbean and inexperienced in working in industrial facilities. Little Rock citizens held clothing drives to improve these conditions, but weakened constitutions and the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic killed 176 of the Puerto Rican workers. A marker stands to their memory in Calvary Cemetery in Little Rock.

All the workers endured long hours and hazardous work conditions. Picric acid production turned their skin and hair yellow, and working conditions were often hazardous; several died in industrial accidents. Workers went on strike several times late in the summer of 1918, and several were arrested for sedition when they grumbled about low or inconsistent pay.

The end of the war brought the closing of the plant. Some thought that, since it was a federal facility, it might stay on to supply the War Department. Production soon ended, however, and parts of the plant were sold off in the following years. Lead from the acid tanks was sold in bulk, buildings were occupied by other industries, and the power plant was ultimately bought by Harvey Couch, who used it to start the state’s first power grid, linking Little Rock and Pine Bluff. Over time, part of the plant was turned into a quarry. The remaining land was eventually used for Interstate 440 and hotels along Bankhead Drive near the Little Rock Airport. Though the facility itself is gone, shells filled with Arkansas-made picric acid constitute a portion of the “iron harvest” in northern France and Belgium that brings in thousands of World War I shells each year.

For additional information:

Demirel, Evin. “Arkansas Mystery: Marker Dedicated to Puerto Rican Immigrants Sparks a Historical Rediscovery.” Sync, July 10, 2012, pp. 10–11. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2012/jul/10/arkansas-mystery/ (accessed November 6, 2023).

Drexler, Carl. “Gearing Up Over Here for ‘Over There’: Manufacturing in Arkansas during World War I.” In The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

———. “The Little Rock Picric Acid Plant in World War I.” Pulaski County Historical Review 65 (Fall 2017): 70–78.

Carl Drexler

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Garver, Neal Bryant

Garver, Neal Bryant Military

Military Science and Technology

Science and Technology World War II Ordnance Plants

World War II Ordnance Plants Picric Acid Plant Headline

Picric Acid Plant Headline  Picric Acid Plant Map

Picric Acid Plant Map

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.