calsfoundation@cals.org

Right to Work Law

aka: Amendment 34

In November 1944, Arkansas and Florida became the first two states to enact what are commonly known as “Right to Work” measures. These laws prohibit employers and employee-chosen unions from agreeing to contracts that require employees to join the union as a condition of employment. Thus, rather than simply granting an individual the right to work, such laws regulate the collective bargaining process to the detriment of unions.

The effort to enact Right to Work laws originated on Labor Day in 1941, when Dallas Morning News editorial writer William Ruggles called for the passage of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibiting contracts that required employees to become union members. Soon thereafter, Vance Muse, founder of the Christian American Association, visited Ruggles and secured the writer’s blessing to campaign to enact state laws to outlaw what was commonly known as the closed or union shop. Ruggles even suggested the name for such legislation—Right to Work.

Muse, a Texan who had long made a lucrative living lobbying on behalf of conservative and corporate interests throughout the South, hoped that planters and industrialists would pay his Christian American Association for organizing and implementing Right to Work campaigns. But he had little success building up interest, mostly because conservatives in the South feared that federal judges would rule such laws to be in conflict with the National Labor Relations Act (1935). He and his Christian American Association did have success, however, in lobbying legislatures in Texas and Mississippi to enact laws making strikers (but not strikebreakers, management, or non-strikers) criminally liable for any violence that occurred during labor disputes.

Arkansas planters and industrialists, led by the Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation, brought Muse and the Christian American Association to the state in 1943 to lobby the Arkansas General Assembly for an anti-labor-violence law similar to the ones in Texas and Mississippi. The Farm Bureau and its allies hoped that such a measure would protect Jim Crow labor relations by making it difficult for unions like the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union to organize agricultural workers. Muse and his group boasted that the measure would allow “peace officers to quell disturbances and keep the color line drawn in our social affairs” and “protect the Southern Negro from communistic propaganda and influences.”

The Christian American Association’s success in pushing the anti-labor-violence bill through the Arkansas General Assembly convinced planters and their allies to take a chance on Muse’s pre-packaged Right to Work legislation. The association used the initiative process to place before Arkansas voters in 1944 a constitutional amendment reading: “No person shall be denied employment because of membership in or affiliation with or resignation from a labor union, or because of refusal to join or affiliate with a labor union, nor shall any corporation or individual or association of any kind enter into any contract, written or oral, to exclude from employment members of a labor union or persons who refuse to join a labor union.”

During the campaign, the association insisted that ratification of the Right to Work amendment was essential to protecting Arkansas workers from radical labor organizers, curbing union power, and maintaining the so-called color line in labor relations. One piece of propaganda warned that if the amendment failed, “white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black African apes…whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.” Similarly, the Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation justified its support of Right to Work by citing organized labor’s threat to the Jim Crow system of racial segregation. It accused the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) of “trying to pit tenant against landlord and black against white.”

The Arkansas State Federation of Labor (AFL), the Arkansas Industrial Union Council, the Arkansas Farmers’ Union, and the Railway Brotherhoods came together to form the Arkansas Voters’ League in an effort to prevent ratification of the Right to Work amendment. The league cast the election as part of a populist class struggle—“farmers, organized and unorganized workers” against “our perpetual opponents—big shot industrialists, plantation moguls.” The league also warned that passage of the amendment would weaken the labor movement, roll back the other gains made by workers under the New Deal, deprive Arkansas workers of the autonomy associated with manhood, and, ultimately, undermine democratic institutions. American Federation of Labor president William Green, however, ordered the federation’s unions to withdraw from the Voters’ League just as the campaign was heating up, and labor’s opposition fell apart.

In an election marked by an unusually high number of irregularities (even by Arkansas standards), the Right to Work amendment—now known as Amendment 34 to the Arkansas Constitution—was ratified. In several of the plantation counties along the Mississippi River where planters regularly bought poll-tax receipts in bulk and voted for their sharecroppers, local officials delayed reporting results to ensure that the amendment had enough votes to pass. Eleven days after the election, only sixty-eight of the state’s seventy-five counties had reported the results. In the end, the secretary of state certified the amendment as ratified, listing the vote as 105,300 to 87,652.

In the wake of the Arkansas vote, Vance Muse boasted of his success, offering the Christian American Association’s services to those in other states wanting to bankroll similar campaigns. Muse also denied that Amendment 34 was anti-black: “ Our amendment helps the nigger; it does not discriminate against him. Good niggers, not those Communist niggers.” Industrialists and planters took up Muse’s offer, and the association helped put Right to Work amendments before voters in several states; in others, forces unconnected to the Christian American Association pushed the measures. By 2017, twenty-eight states had enacted Right to Work measures.

Arkansas’s amendment required the passage of enabling legislation, and, when the General Assembly met in January 1945, four separate enabling acts were introduced. The competing measures caused dissension within the ranks of Right to Work supporters, and the Arkansas labor movement proved to be adept at exploiting these divisions. The session adjourned with none of the measures gaining a majority of votes, and the enabling legislation had to wait until 1947, when the General Assembly was to reconvene.

In 1946, men connected to the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce/Associated Industries of Arkansas, Arkansas Expenditure Council, and Arkansas Farm Bureau Federation created the Arkansas Free Enterprise Association (AFEA) to defend the Right to Work amendment and the anti-labor-violence bill passed in 1943 and to press for passage of an enabling act. When the General Assembly convened in 1947, the AFEA strong-armed legislators into voting for its version of the enabling act. As its executive director later explained, the AFEA recruited “big shots” from each legislator’s home town, and those people then accompanied legislators to the floor to make sure the legislators “did the right thing” when the enabling measure came to a vote. After securing passage of the Enabling Act (Act 30 of 1947), the AFEA went on to lead the fight against President Harry Truman’s civil rights program and manage Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrat campaign in the state.

Soon after passage of the Enabling Act, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act (1947); Section 14(b) of the act explicitly granted states the right to enact Right to Work laws. This removed the possibility that federal courts would strike down Amendment 34 as in conflict with the National Labor Relations Act.

Through the 1950s, the AFEA continued to promote the Right to Work laws as essential to maintaining racial segregation. For instance, in 1958, its director explained that in the face of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions mandating school integration and “race-mixing,” Right to Work laws offered “our only hope at the moment.” He reasoned that these laws allowed unions to remain segregated and for white workers to keep black workers relegated to menial jobs.

Labor unions, though, opposed the Right to Work laws and worked for their repeal. They saw the laws as allowing non-members to enjoy the benefits of union contracts—higher wages, better benefits, due process procedures—without having to pay to maintain the union. The purpose of such laws, labor leaders maintained, had less to do with protecting the rights of individual workers than it did with curbing labor’s economic and political power to the benefit of employers.

Trade unionists had two options for getting rid of Right to Work laws—convincing Congress to repeal Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act or to repeal the laws state by state. In the 1950s and 1960s, most of labor’s efforts went into the repeal of 14(b). But coalitions of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats were able to stymie repeated attempts to repeal.

In 1976, the Arkansas AFL-CIO decided that it could no longer wait for Congress to act and used the initiative process to place a constitutional amendment repealing Amendment 34 before voters. The Arkansas AFL-CIO argued that, by weakening unions, the state’s Right to Work law had lowered workers’ wages, pointing out that the state ranked forty-ninth in per capita income, hourly earnings, and poverty levels. The labor federation insisted that repealing the law would facilitate unionization, help workers negotiate for higher wages, increase consumer spending, and improve the state’s economy.

Business and agricultural groups formed the Freedom to Work Committee to defend the Right to Work amendment. The group’s chairman maintained, “In addition to destroying working people’s rights, the union proposal would keep the state from being competitive in attracting new industry, thus slowing down our progress in gaining more and better paying jobs.”

Although African-American and church groups got behind the Arkansas AFL-CIO’s effort to repeal Amendment 34, leading liberal political figures either remained neutral (Dale Bumpers and David Pryor) or opposed labor’s efforts (Bill Clinton). This signaled to middle-class liberals that repealing Right to Work was not in the state’s interest. In the end, the Arkansas AFL-CIO was unable to overcome business opposition and middle-class indifference to its repeal proposal, which went down to a resounding defeat.

After the 1976 defeat, the Arkansas labor movement went into decline, and serious challenges to Amendment 34 ceased.

For additional information:

“68 Counties Report on Election.” Arkansas Gazette, November 18, 1944, p. 7.

Diane Blair Papers. Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Davenport, Walter. “Savior from Texas.” Collier’s 116 (August 18, 1945): 13, 79–82.

Gall, Gilbert. “Southern Industrial Workers and Anti-Union Sentiment: Arkansas and Florida in 1944.” In Organized Labor in the Twentieth Century South, edited by Robert Zieger. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991.

Kennedy, Stetson. Southern Exposure. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1946.

National Right to Work Committee. https://nrtwc.org/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

Pierce, Michael. “The Origins of Right to Work: Vance Muse, Anti-Semitism, and the Maintenance of Jim Crow Labor Relations.” LaborOnline, https://www.lawcha.org/2017/01/12/origins-right-work-vance-muse-anti-semitism-maintenance-jim-crow-labor-relations/ (accessed December 17, 2021).

———. “The Racist Roots of Anti-Unionism in Arkansas.” Arkansas Times, December 2019, pp. 73–74, 76–77. Online at https://arktimes.com/history/2019/11/26/the-racist-roots-of-anti-unionism-in-arkansas (accessed December 17, 2021).

Schiller, Reuel. “Singing ‘The Right to Work Blues’: The Politics of Race in the Campaign for ‘Voluntary Unionism’ in Postwar California.” In The Right and Labor in America: Politics, Ideology, and Imagination, edited by Nelson Lichtenstein and Elizabeth Tandy Shermer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Michael Pierce

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Law

Law Southern Cotton Oil Mill Strike

Southern Cotton Oil Mill Strike World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

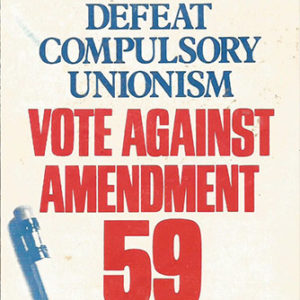

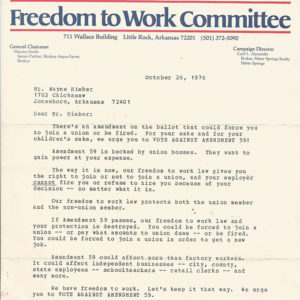

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Anti-Amendment 59 Brochure

Anti-Amendment 59 Brochure  Anti-Amendment 59 Campaign

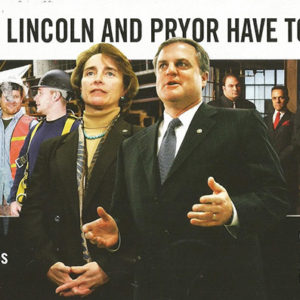

Anti-Amendment 59 Campaign  Anti–Lincoln and Pryor Ad

Anti–Lincoln and Pryor Ad

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.